An Exhibition on Gabriel García Márquez's Long Road to Becoming a Writer

Lance Richardson on The Making of a Global Writer

Gabriel García Márquez: The Making of a Global Writer, which was originally showing at the Harry Ransom Center until July 19th, 2020, is currently closed until at least May 1st because of COVID-19. Lance Richardson visited and wrote about the exhibition before its closing.

*

Every writer has a professional vice, a self-destructive habit impossible to shake, and mine is navigating to Amazon, typing in the name of some masterpiece, clicking on the “Look Inside” function, and reading, for example: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Then I close the computer and go for a long, long walk along the river, despairing at not being able to write anything even one-fiftieth as brilliant.

A published work is like a magic trick. If it’s effective—and One Hundred Years of Solitude can be fairly said to fit that description—it seems effortless, inevitable. The words are arranged on the page in an order that seem so natural and precisely right, it is as though they were always there, just waiting to be uncovered. The labor involved in producing a masterpiece is so artfully effaced that we can barely believe any labor was involved. It just happened, immaculately. We call this genius.

Like many writers, I study the work of geniuses because I’m a masochist when it comes to my own prose, but also because I want to figure out how these masters managed to pull it off. (Joan Didion, responding to a similar impulse, used to retype the stories of Ernest Hemingway.) Perhaps this is one of the reasons that university archives acquire the personal effects of certain writers: All the correspondence, edits, and dead-end drafts offer a glimpse at what “genius” actually entails.

Former Cuban leader Fidel Castro, Gabriel García Márquez, and literary agent Carmen Balcells in Havana circa 1980-1990s. (Gabriel García Márquez Papers, Harry Ransom Center)

Former Cuban leader Fidel Castro, Gabriel García Márquez, and literary agent Carmen Balcells in Havana circa 1980-1990s. (Gabriel García Márquez Papers, Harry Ransom Center)

Gabriel García Márquez: The Making of a Global Writer, a new exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, is an elegant attempt at this kind of demystification. It is comprised of letters, sketches, photographs, newspaper clippings, artifacts and manuscripts drawn from the García Márquez Collection, which the Ransom Center purchased in 2015 for $2.2 million, and then partially digitized.

The large exhibition, which covers most of the Ransom gallery space, can be navigated chronologically, from childhood to glory, or backwards.

“The exhibit seeks to answer the question of how a shy boy from a remote Caribbean village in Colombia became one of the most celebrated authors of the last century,” says Álvaro Santana-Acuña, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Whitman College, who curated the show. Despite what one might assume of a man who was awarded the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature, “it was not easy for García Márquez to succeed professionally.”

Born in 1927 in Aracataca, Colombia, García Márquez—or “Gabo” to admirers—wanted to be a writer from an early age. His first notes about the Buendía family were made when he was just 23 years old, though One Hundred Years of Solitude would not be finished until he was 40. As a young man, he wrote short stories and poetry (“Rains. The afternoon is a leaf of fog. Rains.”), and worked as a journalist in Cartagena and Barranquilla, where he published pieces that showed his affection for modernists like Virginia Woolf. (One column was often written under the pseudonym “Septimus,” for example, which he lifted from a character in Mrs. Dalloway.)

In the 1950s, he tried his hand at scriptwriting, freelancing for tabloids, advertising copy—a piece for a chemical company was titled “5000 años de Celanese Mexicana”—and short novels, which he sold to tiny presses. Few people read them. By 1963, García Márquez feared he might never make it as a professional writer.

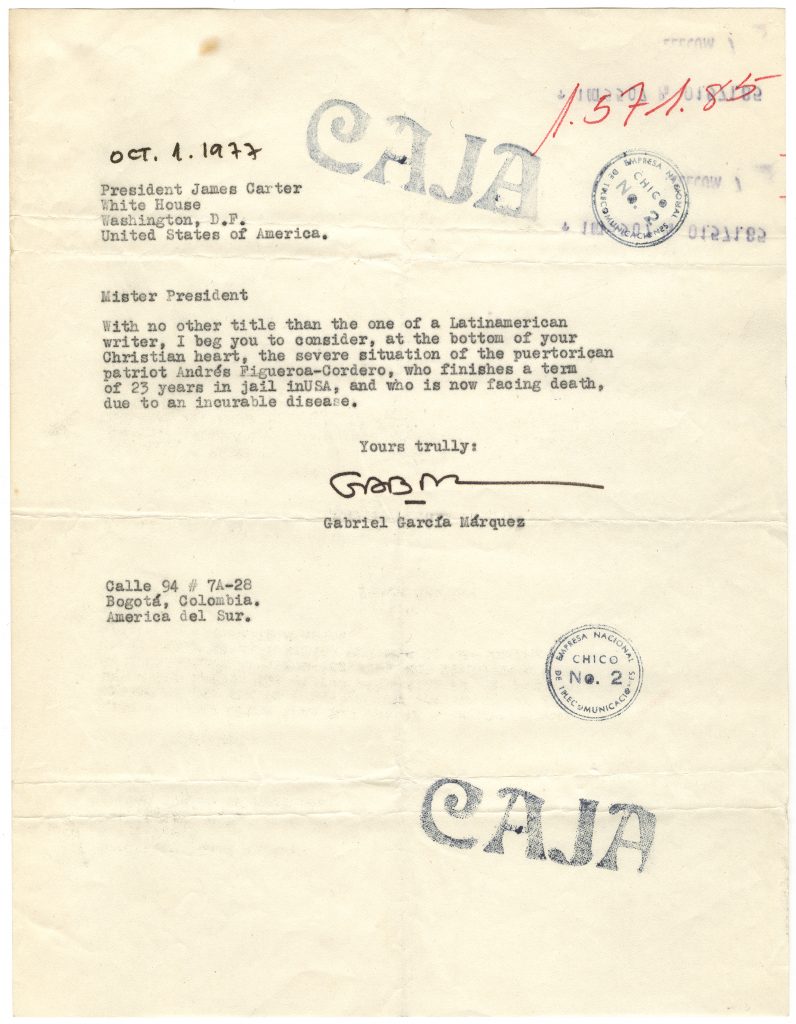

Gabriel García Márquez’s letter to President Jimmy Carter (Oct. 1, 1977), asking him to consider the situation of Puerto Rican Andrés Figueroa Cordero imprisoned in the U.S. for 23 years and at that time facing an incurable disease. Figueroa Cordero was pardoned by President Carter and released in 1978. (Gabriel García Márquez Papers, Harry Ransom Center)

Gabriel García Márquez’s letter to President Jimmy Carter (Oct. 1, 1977), asking him to consider the situation of Puerto Rican Andrés Figueroa Cordero imprisoned in the U.S. for 23 years and at that time facing an incurable disease. Figueroa Cordero was pardoned by President Carter and released in 1978. (Gabriel García Márquez Papers, Harry Ransom Center)

“Talent without discipline rarely takes an artist very far,” says Santana-Acuña, who was invited to curate the exhibition after spending months in the García Márquez Collection to write a book. But Gabo was, above everything else, supremely disciplined: “Being a journalist taught him about the importance of writing effectively first; that is to say, get your facts and the story right, and then you can think about adorning your prose.” In the summer of 1965, he took everything he knew, focused hard for 14 months, and produced Cien años de soledad.

Santana-Acuña’s curatorial choices mirror those that a biographer might make. The large exhibition, which covers most of the Ransom gallery space, can be navigated chronologically, from childhood to glory, or backwards, beginning with García Márquez’s status as a global icon. (In a charming aside, visitors are encouraged to listen to Rafael Escalona’s “El vallenato Nobel,” written in honor of Gabo, by calling 512-690-2043 and pressing 156#).

One Hundred Years of Solitude divides the exhibition in half, with one side progressing up to its publication in 1967, and the other half examining its impact on world literature—and on García Márquez, who went on to use his incredible success to advocate for Spanish-American cinema, ethical journalism, and even Fidel Castro.

Yet the true draw here is an insight into what García Márquez once called the “carpentry” of writing: his techniques, inspirations, and preoccupations. One early short story, reproduced in Spanish, was allegedly written the day after he read Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. Called “The Third Resignation,” it narrates the tale of a dead boy who continues to grow in his coffin—a surreal flight of fancy that would not seem out of place in his more mature fiction.

Santana-Acuña has also included other influences on García Márquez: Faulkner’s corrected manuscript for As I Lay Dying, Joyce’s galleys for Ulysses—Gabo studied Joyce’s monologues and narrative use of time—two manuscripts by Borges, and the manuscript of Hopscotch by Julio Cortázar.

Roger Angell’s rejection letter landed in García Márquez’s mailbox just 18 months before the Nobel Prize announcement.

Cortázar was one of the friends who read and commented on early drafts of One Hundred Years of Solitude, several extracts of which are featured in the exhibition beneath glass. Far from effortlessly dashed off, the pages on show are obsessively revised. In one letter, García Márquez admits that he is tired of working “like an animal,” and that “the most difficult thing is, definitely, the first paragraph.”

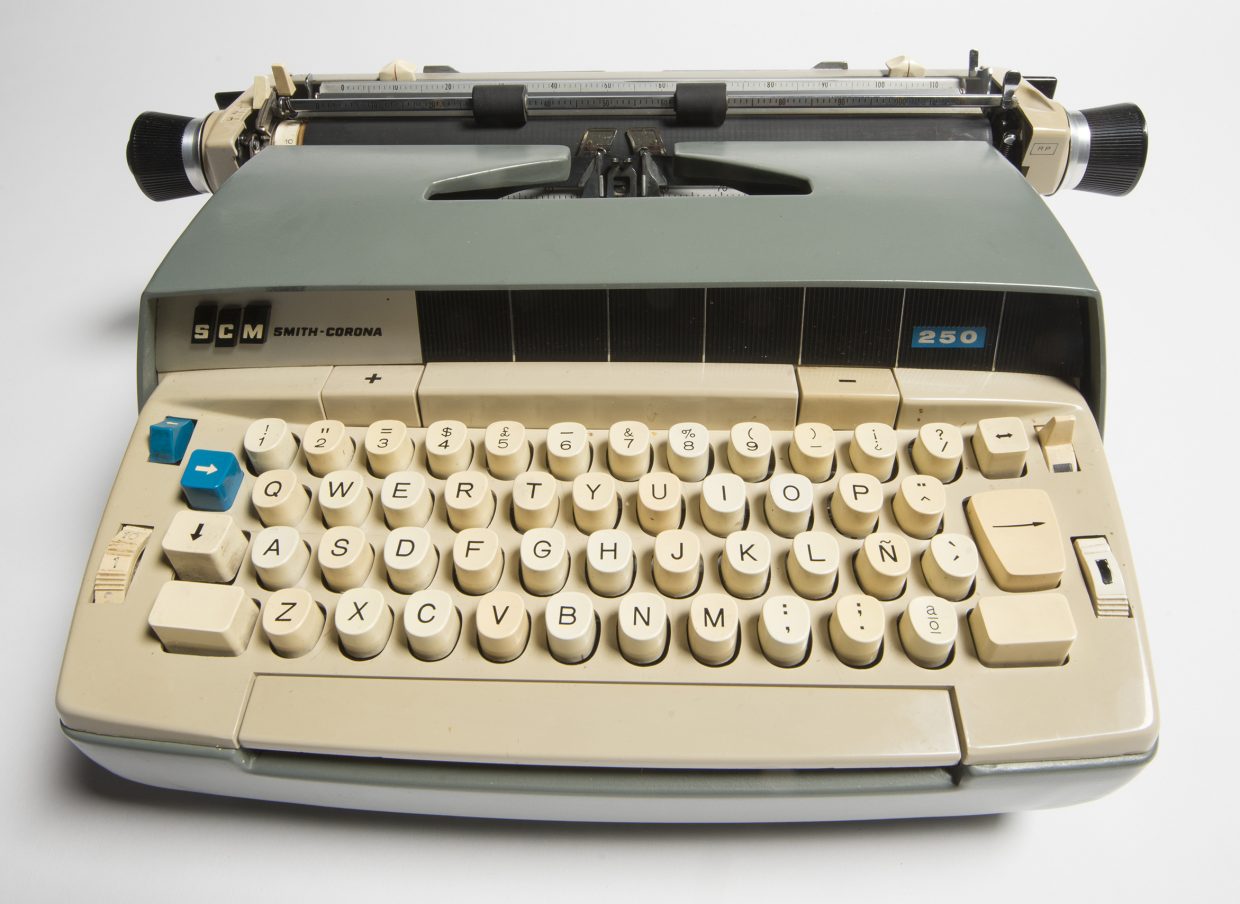

Other surprises include a Smith-Corona Coronamatic 2200—Gabo adopted electric typewriters as soon as they became available—and an Apple Macintosh IIex. “The first computer that went on the market should have been used by me,” he once said in an interview. Santana-Acuña suggests that, in a way, this may have been the case: When it comes to Love in the Time of Cholera, “probably it is among the first works (if not the first major literary works) written completely on a computer.”

Gabriel García Márquez’s Smith-Corona 250 typewriter. (Gabriel García Márquez Papers, Harry Ransom Center)

Gabriel García Márquez’s Smith-Corona 250 typewriter. (Gabriel García Márquez Papers, Harry Ransom Center)

Like many things in the Harry Ransom Center, these otherwise utilitarian objects glow with the aura of their former use and owner. If I were to use the Coronamatic today, I found myself wondering as I lingered beside it, would it help me produce another Autumn of the Patriarch?

But perhaps the most intriguing item is a letter from The New Yorker. Written by Roger Angell in July 1981, it is something that is almost as familiar to many writers as an Apple computer. “We have reluctantly decided not to publish your new story,” Angell writes. Though “THE TRAIL OF YOUR BLOOD ON THE SNOW” shows flashes of “customary brilliance,” the finale “does not quite sweep the reader into acceptance of your daring and beautiful concept.”

Angell concludes, “We look forward with undiminished expectation to the pleasure of considering more work of yours in the near future.” If a more sheepish refusal has ever been sent to anyone, I’ve never seen it.

Angell’s rejection letter landed in García Márquez’s mailbox just 18 months before the Nobel Prize announcement. And there is something comforting about that fact. Even Gabo, who sold 45 million copies of One Hundred Years of Solitude, who has become immortalized as a legend of Latin American literature, could have his flat days. Maybe there’s hope for the rest of us yet.

Lance Richardson

Lance Richardson is the author of True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen, forthcoming from Pantheon Books in September 2025, and House of Nutter: The Rebel Tailor of Savile Row (2018). He teaches in the MFA in Writing at Bennington College, Vermont.