Meet Nancy Wake, the Most Incredible Woman You’ve Never Heard Of

Erased from History Even as She Wrote It

In the early winter of 1934, an intrepid young woman walked into the London headquarters of the Hearst Newspaper Group faced with two choices—return to Australia or get a job. She chose the latter and responded to an ad in the newspaper looking for freelance journalists. Having traveled much of the world already, the idea of continuing her adventures on someone else’s dime appealed to Nancy Wake.

The appointment itself was easy enough to get. She had the credentials—a diploma from Queen’s College for Journalism—but the interview would prove far more difficult. The editor she spoke with liked her marks in typing and shorthand but told her they were looking for someone who could enlighten their readers in the areas of Egyptian arts, literature, and science. The Middle East was, apparently, a growing area of interest for Hearst.

Nancy didn’t miss a beat. “I’ve been to Cairo four times,” she lied. “And I can read and write Egyptian fluently.”

The editor, no surprise, required proof. Would she offer a demonstration? Of course, she’d be delighted. Doubtful, he handed her a pen and paper, then pulled a book off the shelf behind him. He flipped it open to a random passage and started reading. Nancy began to write, in graceful swirls and squiggles, across the page, backward, from right to left. By the time he’d finished, she had filled the entire page with hieroglyphs.

“Now read it back to me,” he challenged.

She did, verbatim. He offered her the job on the spot.

Nancy knew full well that modern Egyptian was written in Arabic, not hieroglyphs. What she’d demonstrated for the editor was neither. Instead, it was a skill she’d mastered at Queen’s College—Pitman shorthand.

Within weeks Nancy was living in Paris and on her first big assignment: a trip to Berlin to interview the newly elected German chancellor, Adolph Hitler.

It was common practice at the time to not print the names of female journalists—particularly freelancers.Nancy’s innate cleverness and her ability to think on the fly would prove to be a valuable, life-saving skill, several years later, when she left journalism and began working as a courier for the French Resistance. She became so successful at this clandestine work that the Gestapo put a five-million-franc price on her head and declared her their most wanted person. Once again, Nancy was forced to make a difficult decision: risk arrest and certain execution or leave her colleagues and escape to England. She chose escape. But, once safe in London, she didn’t sit back and wait out the war. Instead, Nancy marched directly to the offices of the Special Operations Executive and became a spy for the British. Six months later she was parachuted back into France, behind enemy lines, where she led seven thousand French Resistance fighters into battle against the Germans.

Not bad for a scrappy freelance journalist with a gift for lying and calling bluffs.

Nancy Wake went on to become one of the most decorated women of WWII, earning a total of twelve medals from five different countries. We know a great deal about her exploits on the battlefield—thanks in no small part to the autobiography she published in 1985—but we know little to nothing about her work as a journalist.

“If they gave me a medal now, it wouldn’t be for love, so I don’t want anything from them.”I spent months in the summer of 2018 trying to locate the articles that Nancy wrote for Hearst—particularly her interview with Adolph Hitler—to no avail. I don’t think I am alone in this failure, however, because not a single one of her biographers reference them either. After endless emails and phone calls, a university librarian finally explained to me that I was wasting my time. Hearst does not make archived material available digitally and, were I to visit their archives in person, I likely wouldn’t find Nancy’s articles regardless. It was common practice at the time to not print the names of female journalists—particularly freelancers. Once published, the articles were often filed under the names of male supervisors. “It’s just the way it was,” he said.

Nancy Wake survived the war and split her remaining years between Australia and Great Britain. She died in London, in 2011—at 99 years old—of natural causes. To this day she remains entirely absent from US history textbooks and journalism courses, likely because she was not American and was not male. Yet, I imagine, if she had ever been asked how she felt about this, the answer would have been similar to one she gave after being recommended for—and summarily denied— numerous medals in Australia: “They can stick their medals where the monkey stuck his nuts … if they gave me a medal now, it wouldn’t be for love, so I don’t want anything from them.”

(It is worth noting that Australia eventually relented, and Nancy was decorated as a Companion of the Order of Australia. She promptly sold the medal and donated the proceeds to charity.)

Nancy might not have wanted credit for her accomplishments—on the battlefield or in the newsroom—but she certainly deserves it.

__________________________________

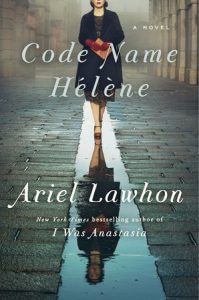

Code Name Hélène by Ariel Lawhon is available now via Doubleday.