An Enigma Embodied: On Monica Vitti, Italy’s Muse of Incommunicability

Joanna Biggs Considers the Role of Feminist Agency On and Off the Silver Screen

First, there is her beauty. (Cinema is a visual medium after all.) Her face has angles but they are soft ones; her skin is pale but dusted with freckles. Her lips are full, her eyes sleepy. Her hair is sculpted but it moves. Her hands ruffle and fly. Her back is a whole landscape. Michelangelo Antonioni was drawn to Monica Vitti by the nape of her neck. She had her hair pinned up, dubbing a film, and he was sitting behind her in the studio. “You have a beautiful nape. You could make movies,” he said, a line you fear would work just as well today. “Just from the back?” Vitti joked. Antonioni, serious: “No.” When Vitti—she of the gorgeous nuca, moving hair, ruffling hands, and angled face—told this story on French TV in the nineties, she laughed at herself.

Antonioni’s trilogia dell’incomunicabilità, often translated as the “trilogy on modernity and its discontents”—L’avventura (1960), La notte (1961), and L’eclisse (1962), an extraordinary three-year run for any artist—was written, shot, and produced by men. These men were directed by another man, one who was in love with Vitti, who herself appeared, indelibly, in all three. Is this the male gaze at its most benign? I cannot deny she is a sort of muse, but she seems never to have been crushed by it.

Vitti described her long relationship with Antonioni as a conversation, moving from the domestic to the artistic and back again, which is the way she liked it. “I need to live with the man I love,” she said, “to work with him, to be with him constantly.” And perhaps because of this, the films are made on her, like a ballet on a particular dancer: Antonioni would notice, say, a joke Vitti made or her need to be alone after a summer argument and alchemize it into art. The films use her qualities to the utmost, so that everyone would be able to see them, forever.

I am often thinking of Vitti’s beauty when I watch her, of the way it makes me pay attention, lose my sense of time, think newly about feminism.

Susan Sontag said that you could find “new masterpieces every month” at the cinema from the late 1950s to the early 1970s. I would settle for the early 1960s: not only Antonioni’s trilogy but Godard’s À bout de souffle, Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7, Resnais’s L’année dernière à Marienbad, Visconti’s Il gattopardo, Clayton’s The Innocents. Yasujirō Ozu was still working, as was Alfred Hitchcock. It was a moment of promise for feminism too: both the pill and abortion rights had arrived. Mary McCarthy was writing The Group, Sylvia Plath The Bell Jar, Betty Friedan The Feminine Mystique. The early 1960s are feminism’s adolescence.

When I watch Antonioni’s films with Vitti, I see a laboratory for ideas about womanhood. Maybe this is where my female gaze coincides with the gaze of the direttore innamorato. She plays the friend in L’avventura, then the mistress in La notte, and then the girlfriend in L’eclisse. And in L’avventura the betrayer, in La notte the heiress, and in L’eclisse the daughter. And then the betrayed in L’avventura, the games mistress in La notte, the ghoster in L’eclisse. The breadth is important. There always seems to be room to go against type: a matter of politics as much as a matter of acting. She isn’t always the girlfriend or always the mistress or always the friend but is allowed to inhabit each role, traces of the previous one lingering in the viewer’s mind.

What sorts of marriages and friendships do women want? When you triumph in the sexual marketplace, must it always be pyrrhic? Is there an inherent and fundamental loneliness to the couple—always together but never in sync— that haunts even the harmonious times? Do women still want to be muses, or would they prefer to be collaborators or—whisper it—auteurs themselves? You watch, and you wonder: When does Vitti seem happiest? When might I be happiest? As women we are often set against each other: the partnered versus the single, the mothers versus the childless, the career women versus the stay-at-homes. The trilogy reveals how false these distinctions are, that whatever our relationship to work, love, or family, we move through aloneness and togetherness our whole lives.

When we watch movies for their stars, it can make us cruel. We make them into archetypes—Marilyn Monroe the sex kitten, Cary Grant the charmer—and then delight in watching them struggle against type. We go to the cinema thinking: Are they going to surprise us this time? It’s rare they do—which is fine by me. I like to be dazzled anyway, and when and if they manage to break the mould, I think: Oh, that’s acting! They can act after all! We win either way.

It is different with Vitti. Liable to slip from bombshell to depressive and back again, her meaning on screen moves. But that sounds unsettling, as though with Monroe you know where you are and with Vitti you are at sixes and sevens, when watching her is much more pleasurable than that. (In fact, Vitti played Monroe, or rather the role based on Monroe, in the 1964 stage production of Arthur Miller’s After the Fall, winning the praise of Monroe’s former husband.) In life, you can’t happily inhabit a fixed role for long, even if you want to; in the trilogy, Vitti’s solution is a generous attitude to the coming and going. After all, the first thing she does in L’avventura is smile.

Monica Vitti was born Maria Luisa Ceciarelli in Rome on November 3, 1931. By eighteen, she was serious enough about her training in Molière and Shakespeare at the Academy of Dramatic Arts that she stayed behind in Italy while her family immigrated to the United States. She wanted to be an actress, not an archetype, not a star. When she died in February 2022 at the age of ninety, after living with Alzheimer’s for several years, The New York Times obituary highlighted her “chilly sensuality and cerebral approach to her roles,” and other tributes called her by her nickname: the musa dell’incomunicabilità (muse of incommunicability).

She didn’t set out to be another Sophia Loren, but in all of these movies she is in love, often playfully, ecstatically so. What’s chilly about that? In L’eclisse, her character, Vittoria, pulls a glass cabinet door between her and Alain Delon’s Piero and kisses him for the first time with the pane between them; later they giggle because there always seems to be one arm too many as they make out on the sofa. The tragedy of being unable to connect arises only when you meet someone whose loveliness inspires you to communicate. Clumsiness isn’t a problem when there is no one to become close to—though laughing at awkwardness brings a certain intimacy. I am often thinking of Vitti’s beauty when I watch her, of the way it makes me pay attention, lose my sense of time, think newly about feminism. On screen, she is making contact of one sort or another, with the viewer if with no one else.

Throughout the trilogy one particular shot of Vitti appears again and again. Antonioni’s camera, controlled by Aldo Scavarda and then by Gianni Di Venzano, frames Vitti’s head as she walks around a new apartment, a new neighborhood, a new landscape. My theory is that Antonioni was composing this shot when he complimented her nape, with the idea of setting off that magnificent neck of hers, but he must have also noticed her hair, curving and shiny, Medusa by way of Brigitte Bardot, and a character in itself. Her hair speaks to me. It is not lacquered or pinned up or hemmed in or easily disheveled. At one point in Red Desert (1964), Antonioni’s first film in color and their last one together, Vitti’s character attempts to communicate her distress by saying, “My hair hurts”—a line that film critics mocked. But have we really watched Vitti’s hair for four years without understanding exactly what she means? Her hair feels, and we feel with it.

Would someone chilly grin as much as Vitti does? Her smile often reminds me of Setsuko Hara’s in Ozu’s movies. Antonioni and Ozu are both makers of calm, subtle, quiet films, and in them the smiles do much to disrupt the meaning of what we see. Hara’s smile is radiant, and it predisposes us toward her. It seems authentic even when it is given at cross purposes: At the end of Tokyo Story, when she agrees with her sister-in-law that life is disappointing and that children inevitably treat their parents selfishly, she smiles and smiles and smiles through the delivery of her lines. Vitti’s smile is not given so freely. She drips it into her performance, catching the camera’s eye at some absurdity or other and laughing. There are stages in her smile: an amused lift of the corner of her mouth at a bitchy comment overheard in an art gallery in L’avventura, a delighted grin when she’s winning a parlor game in La notte, and an openmouthed, toothy laugh at a confetti of chocolate wrappers when the box her boyfriend offers turns out to be empty in L’eclisse. She may be alienated, lonely, and disappointed in all three movies, but a smile is never far off. Things go wrong, and she laughs. People are careless with what they say to her, and she shrugs it off with a half-grin. She glides.

I don’t think being a muse is much of a destiny for anyone, but…at least Vitti had latitude, if not quite agency.

This nonchalance—some must have been native to her, perhaps from her unhappy childhood—may have originated as an adaptation to acting for Antonioni while also being his partner. “What I’d learned in drama school wasn’t much use on the rocks of Lisca Bianca, where we were shooting under such dramatic conditions,” she said of working on L’avventura. “Michelangelo treats his actors as objects, and it is useless to ask him the meaning of a scene or a line of dialogue.” I don’t think being a muse is much of a destiny for anyone, but if Antonioni wasn’t going to give much direction, then at least Vitti had latitude, if not quite agency, to interpret her roles.

She also needed equanimity for Antonioni’s preferred method of capturing unease on film. He would keep rolling at the end of a scene before he said cut, creating a moment of what Vitti called smarrimento, which translates as dismay or confusion. She wouldn’t know if she could drop character or not because direttore refused to tell her. The actor’s guard lowers at the same time as the person herself surges up; the threshold between art and life wavers, and something real seeps in. You can see why it would be interesting to Antonioni and Vitti to pause in the gloaming between their two roles, as it’s interesting enough to the viewer to guess where their artistic lives ended and their romantic lives began. I wonder too if, in the director’s manipulation of the boundary, there is an admission of his powerlessness: It is not his nape, his hair, or his smile. He may conceive, write, direct, cut, and edit, but the viewer only sees her.

If Vitti got to investigate the different romantic and artistic roles on offer in early-1960s Italy on celluloid, what did she then decide for herself in her own life? Antonioni left her after ten years, and once alone, she used her smile for her own purposes. No longer the musa dell’incomunicabilità, she made Italian-language comedies with titles like I Married You for Fun and Kill Me Quick, I’m Cold and was beloved for it. Later still, she wrote a novel and directed herself in a movie. The idea wasn’t to compete with Antonioni—they stayed friends—but to occupy the space she had earned, inch by inch, with her acting.

For a moment in La notte Vitti is captured creating something of her own. Valentina, bored at the party, begins skidding her bejeweled makeup mirror across the checkered floor. She gives her game a goal: She wins a point if the case lands in the middle of a chosen square. Kneeling on the ground in a black cocktail dress held up by two black, thread-like straps, she is losing against herself until Giovanni, a writer played by Marcello Mastroianni, wanders over. “Can you find someone to play with me?” she asks him. “Won’t I do?” he replies. “No, too old.” He isn’t put off, and they play anyway. Soon they are surrounded by partygoers gambling on which of them will win. It’s men versus women, intellectuals versus socialites, directors versus muses. When bets reach sixty thousand lire, he refuses to play. Vitti leans forward on her arms. Her eyes are shining; there is a smile coming. “You only worry about losing. Typical intellectual. Selfish, but full of compassion!” She leads the room’s laughter with her own. “I’m not some kind of racehorse,” he says, indignant. By now, everyone is laughing. She’s won. She devised her own rules, and she won. “Avanti!” she continues. “Is there a fresh horse in the room?”

__________________________________

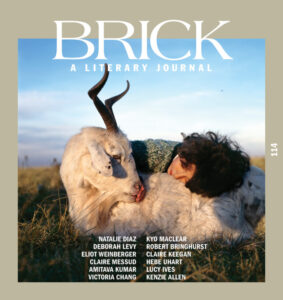

“Smarrimento” by Joanna Biggs appears in the upcoming issue of BRICK Magazine.

Joanna Biggs

Joanna Biggs is an editor at Harper’s Magazine. Previously an editor at the London Review of Books, she has written for the New Yorker, the Nation, the Financial Times, and The Guardian, among other places. In 2017 she cofounded Silver Press, a London based feminist publishing house. She lives in New York.