An Enduring Source of Inspiration: In Search of Proust’s Legacy in Ireland

Max McGuinness Explores the French Writer’s Influence on Generations of Irish Literature

Ireland remained neutral during the Second World War and drew up plans to resist possible attack by Nazi Germany or Britain. The authorities were also preoccupied by a different kind of foreign invasion. Throughout the conflict, Ireland continued to operate perhaps the most extensive regime of literary censorship in the democratic world, banning hundreds of “evil” or “unwholesome” works of fiction.

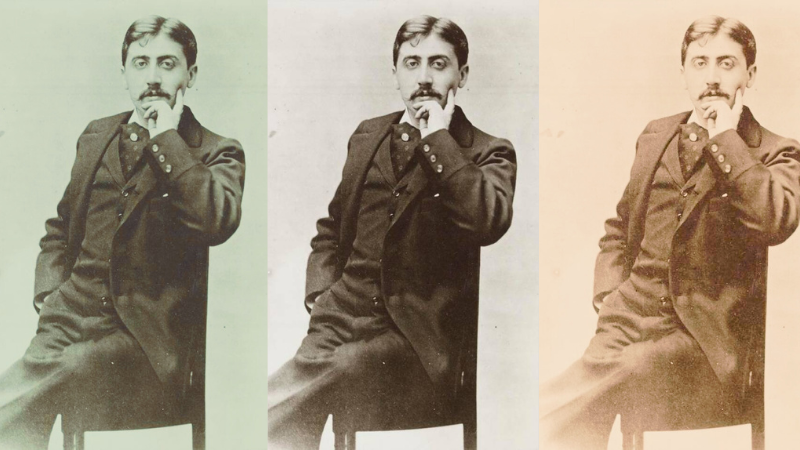

Among its targets was Marcel Proust, who had died in 1922 as he struggled to complete his multi-volume, semi-autobiographical novel of remembrance, In Search of Lost Time, which charts the development of its narrator-hero’s artistic vocation as he circulates through Parisian high society during the Belle Époque.

In April 1943, the minister for justice issued prohibition orders against the final four volumes of Proust’s work (whose English translation, then published under the title Remembrance of Things Past, comprised twelve volumes in total). Each of the offending tomes was, the censors had concluded, “in its general tendency indecent.” That they had managed to overlook ground-breaking depictions of homosexuality in earlier, unbanned volumes gives a sense of the actual diligence they applied to the task of parsing complex works of literature for evidence of “indecency.”

Despite such official philistinism, Proust had already left an enduring mark on Irish letters and would remain a source of literary inspiration for the nation’s writers into the twenty-first century. Though Proust never came to Ireland, his own work also contains echoes of Irish history and culture that epitomize its polymathic, cosmopolitan spirit.

Despite such official philistinism, Proust had already left an enduring mark on Irish letters and would remain a source of literary inspiration for the nation’s writers into the twenty-first century.

More than a hundred years after his death, it now seems timely to explore these rich and productive cultural crossings between Proust and Irish writing, which extend from Proust’s haunted fascination with Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett’s 1931 book on his novel to John McGahern’s final work at the beginning of our century. These connections are the subject of a new volume, The Irish Proust: Cultural Crossings from Beckett to McGahern, featuring contributions from eleven scholars of Irish and French studies about what is Irish in Proust and Proustian in Irish literature.

*

In the summer of 1930, Samuel Beckett was nearing the end of his two-year stint as a language instructor at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. An academic career beckoned back home in Dublin, but the twenty-four-year-old apprentice writer was eager to forge a more artistic path. Having won a poetry prize for Whoroscope, his first published volume, Beckett was recommended for the assignment of writing a book-length essay about Proust, who was already the subject of much interest and praise in the anglophone world (albeit, as of yet, only a handful of extended critical studies in any language).

Beckett duly set to work, not without difficulty and frustration. He even complained to a friend that he was “working all day & most of the night to get this fucking Proust finished.” But, by September, he had delivered his manuscript to Chatto & Windus, who published his Proust in London the following year.

Written with youthful panache and self-assurance, the book already bears the hallmarks of a vibrant artistic consciousness, eager to disrupt literary convention. Beckett was particularly drawn to Proust’s pioneering depiction of involuntary memory—the sudden, revelatory insight into the past that springs from a cup of tea in his Search. Here, in the eyes of the reluctant young scholar, was a vital antidote to the dulling effects of habit and routine. That spontaneous creative energy also represented a liberating alternative to the conventional, programmatic vision of the past that Beckett perceived in the work of Irish Literary Revivalists such as W. B. Yeats. The plodding, mechanical rhythms of everyday, voluntary memory were, he quipped, “of Irish extraction.”

A similar spirit of creativity infuses Beckett’s translations of quotations from Proust’s novel, which feature numerous instances of re-writing that intensify the power of the text by tightening up its form. In these deftly unfaithful translations, we can already glimpse the pared-down aesthetic of Beckett’s later plays and novels as well as his evolution into an author who systematically rewrote his own works as he translated them between French and English.

Shortly before his death, Beckett said of his mentor, James Joyce: “He was always adding to it; you only have to look at his proofs to see that. I realised that my own way was in impoverishment, in lack of knowledge and in taking away, in subtracting rather than in adding.” He could easily have drawn the same contrast with Proust.

For his part, Joyce tended to profess ignorance of Proust’s work, following their sole, awkward encounter at a party in 1922, which amounted, in the Ulysses author’s words, to a “talk consisting solely of the word ‘No.’” Proust, he claimed, had spoken only of duchesses, whereas Joyce himself was more interested in their chambermaids. And yet he also told a friend that he regarded Proust as “the most important French author of our day.” If Joyce was reluctant to express that view publicly, it is perhaps because he had already recognized his chief rival for the title, as the late Edmund White put it, of “the most respected novel of the twentieth century” (which White maintained Proust is winning).

Notwithstanding the young Beckett’s aversion to the cultural status quo back home, he was far from the only Irish writer of the period to have been inspired by Proust. Elizabeth Bowen’s 1929 novel, The Last September, opens with an enigmatic, untranslated epigraph from the Search: “Ils ont les chagrins qu’ont les vierges et les paresseux” [“They suffer, but their sufferings are like those of virgins and idlers”].

The concealed subject here is what Proust calls the “celibates of art”—those, like the doomed aesthete Swann in his novel, who are too coddled and unfocussed to transform appreciation and erudition into their own works of art or scholarship. That quotation alludes to the many Proustian echoes in Bowen’s story set in an aristocratic Big House during the 1919-21 War of Independence. Both Proust and Bowen depict what they know to be vanishing worlds populated by feckless elites—the aristocracy of the Faubourg Saint-Germain in the Search, and their counterparts among the Anglo-Irish Protestant Ascendancy, to which Bowen herself belonged, in The Last September.

Whereas Bowen’s upbringing created a natural affinity with Proust, his work also struck a chord with contemporaries of more humble origin. Mary Devenport O’Neill was the daughter of a rural sub-constable who moved to Dublin to study art, becoming a well-known figure in the city’s literary scene during the 1920s and 1930s. Her sole collection of poetry, Prometheus and Other Poems (1929), includes a poem entitled “Marcel Proust” that depicts a surreal nocturnal encounter with the French author, who arrives at the poet’s home clutching her half-dead cat. The visit becomes the source of an “illumination” through which the poet perceives the emancipatory potential of dreams and memory. Often scorned by her male contemporaries and now largely forgotten, Devenport O’Neill found both an aperture to her own psyche and an outlet to a wider literary world in Proust’s Search.

In a more humorous vein, Flann O’Brien, best known for his experimental comic novels At Swim-Two-Birds (1939) and The Third Policeman (1940), frequently alluded to Proust in his newspaper columns for The Irish Times. Writing under his other, journalistic pseudonym, Myles na gCopaleen, he made sport of the author’s reputation for preciosity and cocked a snook at the figure of “some moon-faced young man who reads Proust.”

More ambiguously, he referred to himself as “merely a spoiled Proust.” These evocations of the French master in a daily newspaper are not the stuff of flattery. They nonetheless both indicate a certain grudging respect for his achievements and assume on the part of the newspaper’s readers a familiarity with Proust’s name and reputation, if not the substance of his work.

Underlying the circulation of Proust’s work in post-independence Ireland was a network of literary salons (including regular gatherings at Devenport O’Neill’s home) and little magazines along with thriving modern-language departments in the nation’s universities. The Dublin Magazine (1923-58), edited by Devenport O’Neill’s friend Seamus O’Sullivan, published numerous articles about Proust and other French authors, as did The Bell (1940-54), edited by Bowen’s lover Sean O’Faolain.

As early as 1926—even before the final volume of Proust’s novel had been published in French—his work began to appear on the undergraduate French program at Trinity College Dublin, a remarkable development at a time when syllabi seldom featured contemporary literature and usually evolved in glacial increments. Trinity is, moreover, where Beckett first encountered Proust’s writing as an undergraduate studying modern languages, prior to arriving at the École Normale in Paris.

The prominence of modern languages, particularly French, in the nation’s academic and intellectual life was a distinctively Irish phenomenon that stemmed from Counter-Reformation ties to continental Europe. At a time when the British elite remained fixated with Latin and Greek, the modern languages provided generations of Irishmen and women with one way of countering Anglocentrism within Irish cultural life. Learning French, German, Italian, or Spanish also offered a means of circumventing Ireland’s draconian censorship regime. For the bans on Proust and other international writers only applied to translations, allowing those with sufficient linguistic ability to consume scandalous masterpieces from abroad in their original form.

The ban on Proust would be lifted in 1953 (following a protest in parliament on his behalf some years previously). And later Irish authors would continue to draw on his work. Brendan Behan is often reductively associated with Dublin pub culture and literary banter. But the Rabelaisian playwright and novelist developed a deep interest in French literature, nourished by a transformative period spent living in post-war Paris. His wife, Beatrice Ffrench-Salkeld, even read Proust to him in bed. And the treatment of homosexuality in Behan’s 1958 autobiographical novel, Borstal Boy, bears clear comparison with the Search, as both authors weave stories of gay love around motifs of sound, silence, and the sea.

Like Behan, John McGahern has traditionally been associated with the vernacular realist tradition. And yet he, too, was receptive to Proust’s modernist outlook, particularly his rejection of biographical reductionism—the idea that a writer’s work could be explained by the external circumstances of their life. In Memoir (2005), McGahern reimagines his own childhood in distinctly Proustian vein as he explores the taboo-breaking intensity of his love for his mother. Though Proust is never mentioned, the French author’s own words even appear almost unaltered when McGahern recounts his youthful absorption in books.

If Proust was eager to differentiate between art and life, this was in part because of the cautionary tale of a literary contemporary who had played fast and loose with that distinction. In his dialogue “The Decay of Lying,” Oscar Wilde’s authorial stand-in, Vivian, quips: “One of the greatest tragedies of my life is the death of Lucien de Rubempré. It is a grief from which I have never been able completely to rid myself.”

At the time of its publication in 1889, this hyperbolic lament for a fictional character—Lucien being the hero of Honoré de Balzac’s Lost Illusions (1837-43)—must have seemed an elegant provocation. In the wake of the Anglo-Irish author’s ill-fated trials and imprisonment in 1895, the bon mot acquired bitterly tragic resonance. For here was a gay man doomed by his failure to recognize that the courtroom was a different kind of stage, one where flamboyant insouciance would bring disaster rather than applause.

If it makes sense to speak of an Irish Proust, it is as one strand within the wider continental perspective that frames his Search.

In contrast to Wilde, who had made little effort to conceal his homosexuality on the stand, Proust opted for a strategy of elaborate discretion. In the Search, his narrator is heterosexual and confronts the mysterious phenomenon of what he calls “inversion” in a spirit of intense albeit scrupulously detached curiosity. Wilde, though unnamed, also appears at the beginning of the novel’s longest sentence as a “poet one day fêted in every drawing-room and applauded in every theatre in London, and the next driven from every lodging, unable to find a pillow on which to lay his head.”

Along with another allusion to his quip about Lucien’s death, that simile establishes the Anglo-Irish author as a terrifying counter-example of homosexual exposure. For Proust—who may have met Wilde and even been the subject of the older man’s amorous attention (though accounts of their meeting or meetings could be apocryphal)—his downfall showed that life featured far keener sorrows than those encountered in books.

In the Search, the pivotal structural device of involuntary memory also has a discreet Irish dimension. When his childhood memories are triggered early in the novel by the madeleine dipped in linden tea, Proust’s narrator compares this experience to the “Celtic belief” in metempsychosis, using imagery that is indirectly derived from Irish folklore.

Other Irish traces in the novel include symbolically charged references to the Irish-descended French president Patrice de Mac Mahon as well as discussions of Irish influences on Norman place names. These Irish echoes may be faint, but they resonate with a more general appreciation of Proust as an omnivorous cultural polymath who was ever receptive to the artistic potential of an infinite variety of cultural materials. If it makes sense to speak of an Irish Proust, it is as one strand within the wider continental perspective that frames his Search.

Oscar Wilde was not the only Irishman locked up in an English prison to draw Proust’s attention. As his health dwindled, Proust took a particular interest in the case of an Irish revolutionary that aroused much public sympathy in France and elsewhere during the War of Independence. In 1920, Terence MacSwiney, the lord mayor of Cork, was convicted of sedition and then died in Brixton Prison after seventy-four days on hunger strike. Throughout that autumn and winter, and even as late as 1922, Proust repeatedly compared his own depleted physical condition to that of the Irish republican martyr. Writing to the journalist Jacques Boulanger, he also linked that sense of doom to the struggle to finish his novel: “Having the ‘Mayor of Cork’’s physical weakness, prolonged by an odious diet, I have the strength to try to go on living to finish my book.”

Such comments strike a somewhat flippant note in view of the disparity between MacSwiney’s and Proust’s circumstances, which included frequent outings to the Ritz in the latter’s case. (Contrary to legend, Proust did not remain eternally confined to his cork-lined room.) But they also have a certain poignancy given that Proust habitually ate almost nothing during the latter part of his life (two bowls of café au lait and two croissants per day, according to his housekeeper, Céleste Albaret). And in his persistent identification with MacSwiney, we can discern, to adapt one of his novel’s recurring metaphors, a form of metempsychosis that yields the figure of an Irish Proust.

__________________________________

Adapted from The Irish Proust: Cultural Crossings from Beckett to McGahern edited by Max McGuinness and Michael Cronin. Available from Bloomsbury Academic. Use the discount code GLR AT8 to obtain 35% off.

Max McGuinness

Max McGuinness is a Research Ireland Postdoctoral Fellow at Trinity College Dublin. His publications include Hustlers in the Ivory Tower: Press and Modernism from Mallarmé to Proust (Liverpool University Press, 2024) and articles about Proust for the Bulletin d’informations proustiennes and Paragraph. He is also a theatre critic for The Irish Times.