An Archive of Associations: When My Father Bought Foucault’s Old Car

Anna Nygren on Writing Between Intertextuality, Obsession and Categorization

One day last summer, at my parents’ house on the east coast of Sweden, my dad says he wants to show me something. He pulls out a piece of paper. It’s a certificate of ownership from the National Archives (Riksarkivet), for the car he bought earlier in the summer.

My childhood was full of cars and car parts and things related to cars. My dad is an expert in British old cars. The best car brands are Triumph, Rover and Jaguar. On our family vacation we went places to buy car parts or for car club meetings, I don’t really remember what happened, I only remember details, like how to open the doors of the cars in different ways, to be careful with their joints. In my late teens and early twenties I almost make a living out of embroidering British car badges and sewing cushions for the back seats of my dad’s friends’ cars.

I once read about essay writing in a handbook for students, where the author compares the best writing of the essay with the construction of the car (assembling different parts, editing) and its worst with crocheting (start at the beginning, finish at the end). I learned that my writing is bad. It’s because I like crocheting. I’m upset about the handbook and what to ask: what does this metaphor know about textile work? I do crocheting all the time, for me it’s the same as writing. But my dad loves cars. And I realize, there is something there inside the car, or in the car or on the roadtrip.

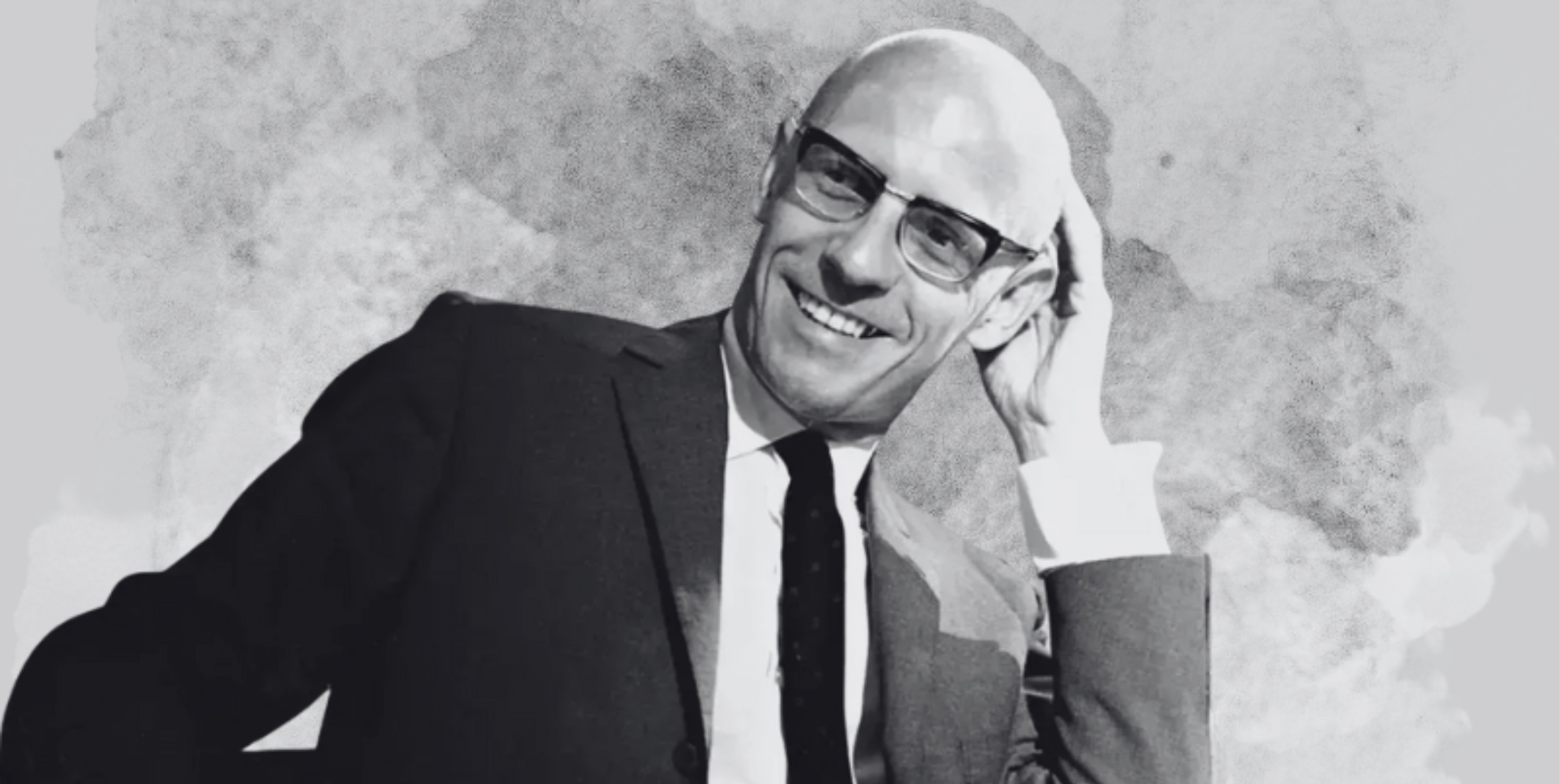

I think of Foucault, the Foucault I think I know, as a haunting and a ghost, in the texts I read, in the conversations I have and hear, in official and unofficial contexts, as extremely serious and as jokes.

Dad hands me the paper, the certificate of ownership from the National Archives. He has found this by means of thorough archival work. I notice that it says in large red text that the paper must not be folded, but that it obviously has been folded in the middle and I say that to Dad. Dad says that it is the National Archives that folded, he is innocent of the paper abuse. He points to the box where the car owner’s name is written. It says Paul-Michel Foucault.

Paul-Michel Foucault lives in Uppsala and is working at the university. Dad says that is like you, that is sort of what you do too, work at the university. Yes. I do. And now I think of Foucault. I search my memory, check the years, feel how my face performs some kind of facial expression, from doubt to rapture to surprise to delight.

So, I say, I think it’s really Foucault’s car.

Dad says:

Who is Foucault?

I say that I think I read a little bit of Foucault every day. I say that Foucault is really famous. He has influenced so much of the things I try to work with, to use for understanding the world. I say Foucault is like a name, that is like written in almost every textbook I pick up.

It feels like something has fallen apart. As if the world I’ve worked my way into, a world consisting of text and theory, and sometimes of the illusion that this intellectual stuff is the only thing worth anything, has collapsed into a childhood memory, as if a name had been given a body that had been sitting in a car that my father finally bought after it had been on sale for several months. As if what is almost a core (if such a thing existed) of my theoretical thought process, but which I never talk to my parents about, is suddenly in the wrong place. A sense of real unreality, a displacement of home and head. It’s a book and a name in the shape of a car. An indirect encounter with an idol, I am starstruck, struck by lightning, I am a fan-girl in memorabilia. It is like falling. Now I don’t want to overestimate Foucault’s importance, but it is also, wow.

I think about things like famous and fanculture and theory and referencing and desire passion pleasure, like this:

Carolyn Allen calls the phenomenon of intertextuality an erotics of citation, in her book Following Djuna (1996). The concept can also be called influence, echo, reference, etc. Allen writes in a queer theory context, a theoretical tradition in which Michel Foucault plays an important role. Allen’s book describes how Djuna Barnes’s novel The Night Woods (1936) influenced generations of lesbian writers and readers, their ways of telling and reading, of relating to text, to sex through text.

Intertextuality is described by Scarlett Barton in perhaps the opposite way, as linked to Roland Barthes’ observation that the author is dead, and that the text is the dissolution of every kind of voice, every beginning and core. At the same time, Barton’s book The Birth of Intertexuality (2019) is precisely a kind of tracing of the concept through the texts and thinking of different authors—which includes sections on Nietzsche’s influence on Barthes and Foucault.

I think of intertexuality as the academic equivalent of a fan community’s reading of books, authors, book characters, movies, actors. Being a fan of a cultural artifact means being a passionate reader (in a broader sense that also includes viewer, listener, audience, co-creator, and that also loosens and points out the porous border between work, creator, recipient). Reading carefully, living with the text, living with a person you have never met, trying to understand thoughts and feelings through another, through a text, a person.

Watching videos of fans meeting celebrities I think of as a study in emotion, in affect. A feeling so strong that the body seems to collapse. There is another concept, hauntology, which refers to how elements of a cultural past, a kind of cultural heritage, haunt contemporary and future cultural phenomena. Jacques Derrida coined the term in his book Spectres of Marx (1993), in which he describes Karl Marx and Marxism (which, incidentally, Foucault first defined as a model but then distanced himself from) as functioning as such a haunt, but other theorists and writers have allowed the concept to flow out, like a ghostly movement, into a range of other kinds of hauntings.

I think of Foucault, the Foucault I think I know, as a haunting and a ghost, in the texts I read, in the conversations I have and hear, in official and unofficial contexts, as extremely serious and as jokes. I think of Foucault as a celebrity with a fan community, as a disembodied body, open to an eroticism, a mosaic, a pornographic intellectualism. And when I meet the car, standing with the hood open, organs exposed, inside my father’s garage, I feel a ghostly excitement. My body and my mind cannot be controlled inside this feeling.

*

Since my dad doesn’t know who Foucault is and I’m bad at explaining, we watch a YouTube video. The guy in the video tells us that when Michel tried to kill himself, his dad sent him to a super famous psychiatrist and the feeling of antagonism he got there founded Michel’s philosophy. A philosophy known for its critique of power and institutions (though the name Foucault has become a kind of power institution in itself, in a way).

My father did not send me away but but he did teach me to burn CDs, helping me acquire a music collection based on small local library’s selection. My taste in music has not changed since, it was cemented with The Ark’s song “It takes a fool to remain sane.” The effects of my dad helping me become a criminal (or otherwise defined as tricking the system of capitalism and ownership) and of the music I came to take to heart, were about the same as the effect of the acts of Michel’s father. I now belong to a kind of skeptically devoted fan-girls-of-Foucault-club.

Dad says that Foucault probably has a point.

Finding Foucault was not easy. Dad tells me about his search for the car’s previous owners. In 1972, the registration number system in Sweden was changed, and the car’s entire previous history disappeared, everything was reset to zero, and it was impossible to find anything about the life of the car before that. But Dad has found a receipt in the car with the previous license plate number, and based on that, he can trace the car back to its birth, where he finds Foucault as the first owner. It is a Work in the Archive.

I think of: the archive, the register, the anamnesis, ownership, materiality, consumption, life, movement… My father may not know Foucault’s name, but he understands the value of Foucault’s methods.

Dad says this is also the car model that Young Inspector Morse drives. Dad knows his British detectives as well as I do. He knows what cars they drive. Vera Stanhope’s car is another favorite (it is Rover, vintage). She inherited it from her father, Hector, with whom she has a more than complicated relationship. I tell Dad that the detective story is probably also suitable for Michel: if you read Agatha Christie’s books, for example, they’re full of the word “queer—both Hercules Poirot and the murderers are often described as “queer.” When I read it, I see it as a Sign, I think it means something.

When I was practicing driving in high school, I got to drive in my dad’s old cars and I learned that the different old cars are like organisms, like creatures. There is a life inside them and we live together. Foucault’s car is a Jaguar. A jaguar is a feline. So the car is also a cat. I once wrote a play about the cuteness of cats and its revolutionary potential, I called it a lesbian psych-opera. Foucault’s car is also very cute, and if I were to describe Foucault, maybe the word cute would fit too.

In the fall, my dad sends me text messages with updates on his further Foucault studies. These have the car as a filter. The car as movement, as thing, as cat, as artifact, as register, as passion, as desire, as possession, materiality, metaphor, theory, practice, horizon of understanding, and as a journey across this horizon.

I follow up on everything he tells me. Foucault drove the car during his time in Uppsala, between 1955 and 1958. One day he went to Stockholm, accompanied by his friend Jean-Christophe Öberg (these two often socialize, and together with Dani, a friend of Öberg’s whom he met during his studies in France). They come back to Uppsala with the spectacular Jaguar. The people around are astonished; in Uppsala they are used to something a little more modest. But Foucault gets money from father, despite the complicated relationship.

I think of the fold, of two sides being put together, of the thing that is the fold that is hidden on the inside when the fold is folded, the hidden things and the forbidden, I think of living there.

Jean-Christophe, Dani and Foucault are partying. Later in life Foucault will become more ascetic, but not yet. He likes to drive fast, often having little accidents. I imagine the three friends as a kind of ménage-à-trois, it’s like a game, sometimes they dress up, I imagine it as a life outside the archive and the academy, I think about what you have to do to survive. Triangles of drama. Like an adventure and conflict. I think of the family vacation.

I’m learning all this from my father, who, in parallel with his research into the biography of the car, has started reading The History of Madness. Dad drives the car. Mom says anxiously on the phone that she wonders if he thinks he also has to drive like Foucault. In Uppsala Foucault was most famous because of dangerous driving.

I think about Uppsala. The city. Between 1922 and 1959 it was the center for the study of eugenetics in Sweden. It was a center for so-called racial science. It was the knowledge production of the so-called Nordic of the so-called difference between the so-called Swedish, Finns, and Sámi population of the so-called human of the so-called body. I think about names and naming. It was a love story of violence. It was run by a man called Herman Lundborg he was a race biologist the really wanted to discover something about bodies and morals and cleanliness. I think of it as violent love that is very close to hatred, and there is another aspect of love also because Herman fell in love with woman named Maria Isaksson, a woman he considered of a lower race. I think about this relationship so much. I think of this and the dangers of love and the dangers of power.

I look at the city map and think of the places were the car could have been parked. The views from there. What did the eye of the Jaguar see? I think of universities as knowledge institutions. Carl von Linné, (1707-1778), famous biologist who named so many species, also lived in Uppsala for a long period. I have read that he is called the Father of modern taxonomy. That is naming. He gave names to animals and flowers he discovered worlds by attaching words to things. I think of naming. I think of modern. I think, again, of fathers. I think it is a love story.

The species of feline, the Jaguar is the largest cats living in america. My dad tells me that Jaguar The Car was first called Swallow Sidecar before but they changed because the Nazis had stolen the two Ss. I think of a cat and a bird and a cat eating bird and whether the globe and its temporalities would need to be tilted for the habitats of swallows and Jaguars to meet. I think of changing names, of being forced to change or choosing to change.

In the ID-paper of the car, it’s color is named: Lavender Grey.

Lavender, I have learned, is a color of resistance of gay resistance. It feels like a secret sign has find a home in the car and it fills me with something—something I think it is poetry of archives. Like Michel and lavender a scent of the flower a color of cars and cats and others.

In Swedish, grey is Grå. There is an author named Maria Gripe, who wrote 3 (!) books about the two children Hugo and Josefin. Josefin was first named Anna Grå but Josefin felt the name Anna Grå as a prison. She cut the name out of her and put it in a shoe box and buried it in her wardrobe. I read the book and I felt my name, Anna, infused with sadness. At the same time, I was reading Wilhelm Moberg’s books about Swedish migrants moving to America. These books are also about a child named Anna. She is starving because the family is poor. One day she finds porridge. Her mother had left it to thicken during the night and when Anna was eating, the porridge grew in her belly making her inner organs explode and she died. The family is so sad after her death they leave their home for America. I think of the name Anna, as filled with the sadness and funeral and death by eating and death by hunger.

I think of species on the arc, I think: it takes a fish to remain sane. I remember visiting Uppsala and the botanical garden as a child. I only remember salamanders in a pond.

*

I think of a car. A paper telling the story the ownership belonging defining. I think of the rules being broken. DON’T FOLD. But it is folded. I think of the fold, of two sides being put together, of the thing that is the fold that is hidden on the inside when the fold is folded, the hidden things and the forbidden, I think of living there. Like a hole between worlds of systems. I think about the crime, folding when forbidden, and what is called a crime and who is forgiven for breaking. Some are. I think if the crime is a fold. I think about the breaking of laws and normalities, the break in the fold, the things that just accidentally happened. I think about an ambiguity inside the fold, the mirroring sides of paper. I think of a fold in time and place. How everything seems to be folded and carrying things inside. I think about cars and families, I think about reading and things, about words and worlds. There is too much. The thought is feeling dizzy and messy and muddy and tired but still flying. The thought is difficult love.

__________________________________

blush / river / fox by Anna Nygren is available from Milkweed Editions.

Anna Nygren

Anna Nygren is an autistic, queer, and neuroqueer writer, artist, and translator. They are the author of several previous Swedish-language works, including their play-experimental translation of Hannah Emerson’s chapbook You Are Helping This Great Universe Explode. As an artist, they work primarily with textiles and are currently at work on a piece about fish, neurodivergence, hospitals, and ideas of what a Good Life is. Nygren lives in Gothenburg, Sweden, with their cat, Zlatan.