Amy B. Reid on Translating the Very Book She Needed to Read

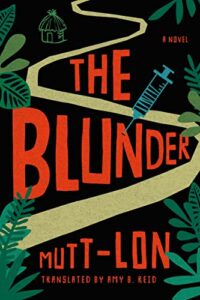

On Mutt-Lon's The Blunder

In March of 2021, when I was struggling, like everyone else, in the claustrophobic reality of the pandemic’s second year, a literary agent in Paris wrote: he asked me to read a novel.

As I opened Mutt-Lon’s Les 700 aveugles de Bafia (Emmanuelle Collas, 2020), I quickly realized just how much I needed that book. It is a raucous, madcap adventure through the tropical jungle, far-removed in place and time from my present, and yet the perfect homeopathic remedy for what ailed me.

Set in the 1920s, the novel focuses on Damienne Bourdin, a young French doctor who needs to escape—from her profound sense of alienation, from the traumatic loss of her infant son—and so decides to hop on a boat headed for Cameroon to join in the fight against sleeping sickness. (Remember the tsetse fly from The African Queen?) As spring stretched into summer, this story helped me to keep my sanity during endless lockdown: I translated it as The Blunder.

The magic of Mutt-Lon’s writing is that he takes Damienne Bourdin’s desperation and turns it into the antidote for our own. He blends escapism, laughter, pop-culture references, and sexual tension into a parable for our time, a caution against the blindness of racism and a paean to both human connections and, of course, literature.

Yet I had a hard time explaining my enthusiasm for this project to friends: I’d say, “Oh, you see, there was this case of medical malpractice in the 1920s, when a misguided French doctor screwed up the dosing of a treatment for sleeping-sickness and blinded hundreds of people in Cameroon… No, no, it’s a comedy!” How could I explain that the novel that had me in stitches was about colonialism run amok? And even worse, that it centered on the hubris of those who sought glory in the fight against a disease and caused the blindness of hundreds of their patients?

Mutt-Lon’s novel is based on his archival research into a particularly dark moment in Cameroon’s colonial history: a moment when the French, who’d been given a mandate over much of contemporary Cameroon by the League of Nations, were trying to both solidify their control and eradicate sleeping sickness, or trypanosomiasis, which was ravaging the region.

His story starts, then, with Dr. Eugène Jamot, who led the French fight against the disease, creating mobile health units to treat patients in remote villages; a statue commemorating his efforts still stands in front of the Ministry of Public Health in Yaoundé.* The author is clear that his initial goal was to set the record straight, to reconcile the enduring public recognition of Jamot with the erasure of the “blunder” that cost so many their sight.

While his protagonist, Dr. Damienne Bourdin, is a fictional character, many others are real, including Dr. Jamot and Dr. Monier, the paramount chief Charles Atangana—who also plays a role in another novel I’ve translated, Patrice Nganang’s Mount Pleasant (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016)—and, perhaps most notably, Teketekete, the flamboyant “witch-doctor.”

As I worked on the translation, Mutt-Lon and I chatted on WhatsApp, about his work and mine, about our experiences of the pandemic on opposite sides of the world.

As I worked on the translation, Mutt-Lon and I chatted on WhatsApp, about his work and mine, about our experiences of the pandemic on opposite sides of the world. I loved hearing the sounds of bustling Douala as he walked along the city’s streets and I was fascinated by how he wove archival details into his plot. (He even sent me a picture of the actual Teketekete so I could see the “mane” of his headdress.) But it is Mutt-Lon’s talent as a storyteller—his ability to frame dark truths in a tale of comic misadventure—that makes this novel work. He doesn’t turn away from our human failings but illustrates the importance of our need to connect.

The Blunder is a profoundly generous and humanist novel, inviting us to laugh not at, but with the foibles of his characters. Stylistically, Mutt-Lon owes a debt to Voltaire’s philosophical tales (think Candide or “Zadig”), where the protagonist’s quest is repeatedly paused so that stories can be traded, and where characters are more allegorical than fully fleshed-out. That attention to story-sharing is part of the novel’s humanism.

But it’s the moments of slapstick and the pop-cultural references that keep me chuckling. Even if you didn’t spend some of your childhood watching Johnny Weismuller’s Tarzan series from the 1930s-40s, you have to laugh as Damienne (disguised as a nun) dashes through the jungle, shedding the layers of her habit and, along with them, the presumptions of France’s “mission civilisatrice.”

Because that, too, is the point of this novel: to challenge racist and sexist stereotypes, those that shaped the colonial encounter in Africa and those that continue to haunt us today. The century between the events of the novel and our present day allows readers the space to recognize the failings of the characters and the structures they represent, to recognize and redeem our shared humanity.

It is significant that redemption in this novel hinges on literature. Damienne fails in her attempt to play the hero in Africa, but once back in France, she finds not only peace and success as a writer, but, in the end, enough perspective to write a novel based on her first-hand experience of colonialism’s blunders. And so The Blunder concludes with a wink from Mutt-Lon, who tells Damienne’s tale to set the record straight. It would seem that he, like his protagonist and like his readers, needed this novel.

I completed my work on the translation this winter, but now, as it becomes clear that Covid will be part of our lives for the foreseeable future, I realize how much I still need it, and how much I’ve gained from my connection with Mutt-Lon. The Blunder is a comic adventure that challenges us to grapple with personal and collective failings, and that reaffirms the resilience and beauty of our humanity. Don’t you need that too?

_____________________________________

Mutt-Lon, which can be translated as “homme du terroir” or “man of the land,” is the literary pseudonym of Daniel Nsegbe, who lives in Douala where he works as a television news and film editor. The Blunder is his second novel, and the first to be translated into English. His first novel Ceux qui sortent dans la nuit (Paris : Grasset, 2013) won the prestigious Ahmadou Kourouma Prize in 2014.

* A useful overview of Dr. Jamot’s campaign against trypanosomiasis and its commemoration, including a picture of the monument at the Ministry of Public Health, can be found in this article by François-Xavier Mboppi-Keou, et al (2014), The Legacies of Eugène Jamot and La Jamotique (nih.gov).

The Blunder by Mutt-Lon and translated by Amy B. Reid is available now.

Amy B. Reid

Amy B. Reid is an award-winning translator who has worked with Patrice Nganang on multiple projects since 2001. In addition to When the Plums Are Ripe, she translated Nganang’s novels Dog Days: An Animal Chronicle (2006) and Mount Pleasant (2016); she is currently working on Empreintes de crabe (2018), the final volume in Nganang’s trilogy about Cameroonian independence. In 2016 she received a Literature Translation Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts for When the Plums Are Ripe. Her other translations include Queen Pokou: Concerto for a Sacrifice (2009) and Far from My Father (2014), both by Véronique Tadjo. She is a professor of French and Gender Studies at New College of Florida. Her translation of The Blunder: A Novel by Mutt-Lon is available now.