She wears knee-length socks because her feet are cold even in summer. She sits on the edge of the bed and rolls them down—shin, calf, ankle—then stops. She rights herself. Her stomach stops her from bending over. She takes a deep breath, stretches her arms, and finishes the job. She folds her socks and places them under her pillow. They’re for sleeping. Marília may not be sweet, but gazing at her from the other half of our bed, I can’t help loving her.

There goes Marília into the kitchen, and I think of how I will soon be roused by the sound of metal clanging, drawers closing, and the whistling of an old tune we no longer know the lyrics to. I face the window, its blinds still shadowy from twilight, close my eyes, and smile. The racket begins. She doesn’t do it on purpose, her hands just don’t know silence. The door slams, and from the depths of our home, I hear the same old melody. I wonder what song it is. I figure it must be ours.

I know that soon I’ll have to pretend I’m fast asleep, because Marília will return to bed with coffee and some toast and, time permitting, a flower penned on a napkin. Marília likes remote-controlled cars, clothespins, skirts with pockets, and plants. She would never, ever pluck a flower. So she draws them.

The door opens. Marília sits on our bed, without the tray. She touches my leg, and I pretend to have just woken up. Her silhouette is drawn by the now-bright window blinds. I hold her jittery hands and know that something is wrong before even opening my eyes. I ask what the matter is. She tells me she is forgetful. I say we are. She looks at me gloomily and says she made coffee without the grounds and burned the toast. I scrunch up my forehead in confusion. She repeats that she brewed the coffee without the grounds, so there was only boiling water in the coffeepot, and as she poured the water into the coffee mugs, she stood quietly for a moment, perplexed. Which was when the toast burned. She tells me she’s old and forgetful. I say we’re two forgetful old ladies.

I look at her hair, now on my lap. She lies on her side and asks me to cover her feet, “Just my feet,” she says, and open the windows. I stretch my back and arms until I reach the cord for the blinds. The light unveils us: my blemished hands on her white hair. How many years has it been, Marília? How long have we been carrying on this Sunday-morning ritual? I think, but I say nothing. Marília seems to be crying a little. If so, it’s on the inside. She tells me she’s going to get breakfast ready. She gets up and walks away.

No flower this time, I see. I don’t dare ask why. I sip my coffee slowly so that I don’t burn my chapped lips. I take small bites of my bread so as not to choke on any harder bits. Marília eats too, her gaze down. A new bashfulness has risen between us. I finish. I look out the window again. It’s a lovely day. I feel like taking a walk around our yard. Marília stands up and places the paddle walker beside the bed. She knows I want to get up by myself, and I do. Though there are only a few stairs, they still give me trouble. Still, I don’t want an elevator in the house and I can’t stand the thought of a wheelchair ramp. Marília opens the door and we walk out into the morning light. It’s colder than I anticipated. She grabs a knit blanket we’ve had forever and drapes it on my back. She gives my shoulders a hard squeeze with her clunky hands; she still hasn’t figured out the exact amount of affection to extend after all these years. I like it. Because I know our love is contained in that act, in that force. And we stand there, behind the wall that shelters our backyard from the street, that shelters our lives from passersby.

Two old women live there, in that house. They’ve been living there for years, those two old women. There’s something about those two old women who’ve been living there together for years. There, in the house of those two odd old women.

We’re two odd old women, Marília and I. And as I think of us, the sun glides past the orange tree and starts to warm my head, a bit too much. I try to get up. My legs lost their strength from night to day, and I never found out why. I went to doctors, magicians, healers, but none of it was any use, I never got the strength back. And I was the one who used to enjoy taking long walks, walking around the neighborhood, hiking in the woods, up the hills, by waterfalls—why me? Now I can barely get across my own patio. So I just sit quietly on the lawn, five steps from the chair I was sitting in before, because I find it hard to balance. I glance back at the house. I can’t spot Marília. I can’t stand and I start to feel anxious, but then she emerges from behind the pillar and asks if I’m all right, if I fell, did I hurt myself, and runs clunkily to help me. Before she reaches me, I tell her I’m fine and invite her to sit on the grass. She grumbles about the dew but sits down anyway. Grumpily, she tells me I’ll catch cold, but still she stays. She pats my leg a bit too hard, which I take to mean she loves me and that she’s sorry about everything. I smile and say I want to go in, even though I don’t really. I go because I know she wants to.

Marília likes routines. On Sundays, she gets up early and makes us breakfast. Then we sit on the front porch for a while. If there’s sunshine, we sit in the yard. After this, she likes to go inside and read the paper. On Sunday morning, I used to go for walks, but now I sit and read the paper too. We eat, then we nap, then we watch TV, then we eat again. Then, before going to bed, we look at each other for a very long time. We look at each other so that we can try and understand how on earth we got to this point. We never do. We always do. We are very quiet; we’ve always enjoyed silence.

Marília is helping me bathe. She washes my back with her rickety hands. She is still ashamed of our bodies. Or maybe it is this new, age-old bashfulness. She shampoos my head three times, and I can tell there’s something wrong, but I don’t say a word. I’m scared. It’s fair for me to be scared. But it would be unfair of me to show her my fear. Marília is constantly afraid of everything. She may seem tough, but on the inside, she’s scared to death. For my part, I’m still and once again scared, and every day I pray we will die together, because I couldn’t bear to be on my own, nor could she. I’ve thought of taking care of it myself. Of doing it quietly, of getting into bed with Marília, in her sleeping socks, and mixing something soothing into our nighttime tea. Hopefully we would never wake up. I’ve only ever thought about it, though; I don’t have the courage. So I pray. I pray we’ll be together, as together as we’ve always been, now and at the hour of our death.

*

The following Sunday, Marília wakes up, then wakes me up with the scent of coffee, the sound of drawers closing, and our wordless tune.

__________________________________

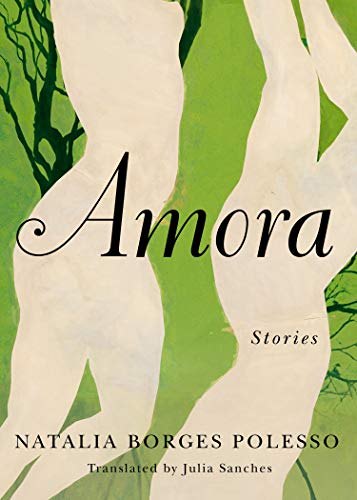

Excerpted from Amora: Stories by Natalia Borges Polesso, Translated by Julia Sanches (Amazon Crossing, 2020). Reprinted with permission from Amazon Crossing.