Amor Towles on Bringing a Historical Setting to Life

"History is the painted backdrop."

As told to Lit Hub senior editor Corinne Segal. The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

I don’t start with a focus on a particular historical period or anything like that. Over the course of my life, an idea will present itself as an interesting story, and it usually comes in the form of a one-sentence premise. With, for instance, The Lincoln Highway, the premise that struck me was a kid getting driven home by a warden, having done time in a juvenile facility of some kind, and he’s getting ready to—having kind of paid his debt—start fresh. And it turns out there are two kids hidden in the trunk of the car, two fellow inmates. Usually when I have a notion like that, quickly—I mean within a matter of hours—I can see a lot about that. I don’t pick a topic to research and then write a book. What I do is pick a story that grows out of an arena that I have been familiar with for a long time.

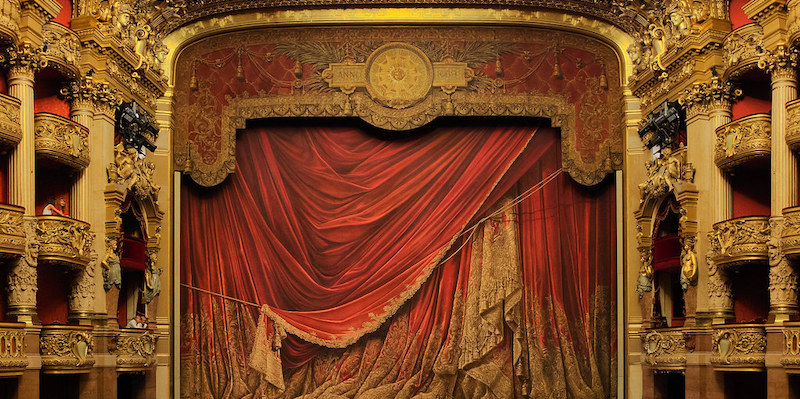

My approach to writing a book is very much like a stage set. If you went to Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, for instance, and you look at the very back of the stage, through a set of French doors, we can see a cherry orchard in the distance—in the afternoon light, let’s say. You’re looking through the living room, through the French doors, and there’s the cherry orchard in the distance and it’s in bloom, perhaps.

The picture that we see from our seat in the theater is, of course, painted canvas, because that’s what a theater set is going to tend to be, like at the opera. And it is painted with care, using Renaissance rules on perspective to give us the depth of illusion. But if you look at the style of painting on that canvas, it’s not hyper-realism because that would look very weird to the eye if you were sitting in the theater. Instead, it’s probably more of an impressionist style—so, gestures of leaves and the petals, to give that sense of the afternoon light and the movement of the trees, and to give a sense that it’s in the distance. For me, history is the painted backdrop. I really don’t care that it be very precise. It should not be very precise. It’s not hyper-realism. It should be impressionist.

There’s a multi-year design phase when an idea has grabbed my attention. I’m thinking about it over a period of years, filling notebooks where I’m imagining the story in great detail, and I’m doing that for multiple stories at any given time. When I set out to do a new book, very often I’m looking at the different notebooks in my office and saying, Which of these am I going to do? It’s a multi-year process. It takes a couple of years for me just to get through the design.

Then I transfer all that imaginary work into a detailed outline that describes the book chapter by chapter, scene by scene, all the characters and their backgrounds, settings, all the events right through to the final page. That’s a pretty extensive outline, somewhere between 25 and 40 pages. And then, once that’s ready, then I would start to write Chapter One.

The reason that I am so interested in outlining … is that it serves what I’m trying to achieve in the novel. One of the things I’m interested in is how the novel can almost feel like a symphony, where there are movements over the course of the novel. It’s like how there are motifs or themes that are picked up and visited over the course of a symphony, perhaps played by different instruments—maybe this theme is played by an oboist as a solo, and then suddenly it’s in full instrumentation ten minutes later. When you get to the end of a novel, there’s this feeling of the culmination of all that you’ve been listening to coming to bear on the final conclusion. That’s really what I’m interested in doing in the novel, to some degree. And for me to achieve that outcome, it requires planning.

One of the other reasons I’m very interested in outlining—a different but equally important reason—is that it is through outlining that I free up my imagination, my subconscious, my poetic sensibility. That’s a counterintuitive element. Having the structure and planning in place, it means that when I’m entering a chapter, I am not [using] that portion of my mind to decide what’s going to happen or who’s going to appear or what do they look like or what does the room look like. Instead, because I know all those factual components, I can allow my subconscious to be entirely in charge of the way in which the chapter is going to sound and the way in which it’s going to be realized: the imagery that’s going to be used, language, metaphor, allegory, all that is coming out of my subconscious and my poetic sensibility.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

__________________________________

The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles is available via Viking.