Emerson had kissed his wife when he came in, which was the right thing to do. Even though she’d been sitting at the kitchen table, empty bowl before her, with the spaceless look in her eyes that made him think he could slap her and she might not even notice. She started at the sound of his voice. His lips grazed her hair.

“Making headway on the human condition?”

Retsy gave him a look—the kind he respected and, in a way, loved. One of idle disdain. He didn’t think she held him entirely in contempt, but that she could express the mo‑ ments she did with such a lack of restraint appealed to him on a primitive, sexual level. So he kissed her again, this time with feeling, and told her about the crash.

Upstairs, he stripped off his sweater and pants, the belt buckle sounding faintly against the floor. There was no need for the change of clothes: though he had come from the city, he’d not worn a suit to the office and what he was about to put on would hardly be different from what he’d removed. Still, after an ordeal like that, he wanted something new.

Emerson preferred to receive visitors having spent at least a day or two in the house. Being there beforehand ensured that when he opened the door, clapped them on the shoulder, and lifted their children, it was clear that he belonged in some essential way, that they were his guests, that long after they’d gone he would stay. Perhaps, then, the unnecessary change in attire was an attempt to achieve some version of this effect.

He dressed as one would expect. He entered clothes like opinions, with the graceful assurance of someone who has not questioned their choices. Legs, arms. The small leaping of muscles, the suggestion of strength. Any broader and his mouth might have been too large. Instead, his smile held like an embrace. Dazzling teeth, lips like folds of rich fabric, a smile in which one wants to believe. It was the kind that can only belong to a man: it had no sense of history; it seemed unaware of the world.

He was not smiling now, however. He was pulling on his slacks and wishing Amos were already there so he could fig‑ ure out how he felt about what had happened. Which was that he’d hit a woman with his car. True, she hadn’t died, and the consensus was that she’d be fine—but still, it was something, wasn’t it? Plus, the details which emerged after had raised big‑feeling questions, questions he didn’t want to think through on his own.

Retsy had said the right things, the ones to be expected, but there was a limit to how far she could go. When it came to thinking, she was like someone who tidied but never cleaned. He laughed to himself. That was a clever way to put it. A little mean, yes, but so the truth tended to go. He could even imagine it slipping out one day as something he actually said.

Anyway, Amos. The thought of his friend made Emerson pause and look toward the barn. His mood brightened. His chest lifted with a pleasant, deliberate breath. Something about his friend seemed to promise a purging. Time spent with Amos was like taking a damp cloth to dusty windows: in its wake, the world of nuance sprang forth. He should tell him, Emerson thought. Why not say it exactly like that?

Oh, but Amos already knew. Decades now, their friend‑ ship. Since college, since the first day of college. They con‑ fided in one another, they hugged. Not like men, but like friends. Real, loving hugs, clutches without irony. People en‑ vied them; they measured their own lives against what they had. He’s my Amos, one might say. It wasn’t true, of course. But Emerson allowed them their hope.

Through the wall he heard Sophie call to Retsy. He smiled at the tone. They weren’t fighting, but it had an edge. Sophie was newly sixteen, and the word itself—Mom—had become a soiled rag, one she uttered as if holding at arm’s length.

She’s awful to me, Retsy had complained recently. Oh, stop, he said, patting her knee. Amos says Anna’s the same with Claire. Then he kept reading—a history of great battles. Turning the page, Emerson wondered whether, had circumstance demanded, he might’ve been shown to possess a similar genius.

Sophie was going downstairs. A quick, sock‑footed patter described her descent. He could picture the way she’d trace the railing with the tips of her fingers. He pulled at his cuffs and inspected his palms, brushing them clean of nothing. He had not once looked in the mirror. He was vain, of course, but it was a powerful kind. He did not stop to wonder. He did not need to be reminded.

He would go down and make sure they weren’t at each other’s throats. Or, if they were, he’d break it up and lighten the mood. He was still strong enough to heave Sophie over his shoulder. She claimed to hate it, but he wasn’t sure. Be‑ sides, it was his birthday, he loved her and it was fun.

__________________________________

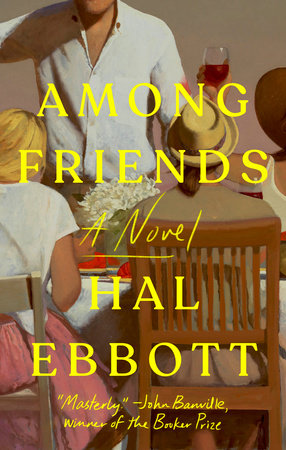

From Among Friends by Hal Ebbott. Used with permission of the publisher, Riverhead Books. Copyright © 2025 by Hal Ebbott.