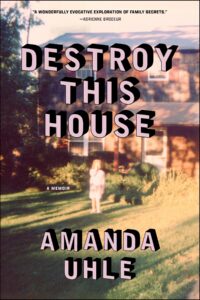

Amanda Uhle on Using a Childhood Photo as the Cover of Her Book

“All I ever wanted was an accurate portrait of who my parents were.”

My mother was the impresario of our outfits. When I was a kid in the mid-80s that meant corduroy elastic-waist pants and turtlenecks for me, cuffed sweatsuits in primary colors for my brother. The Easter I was seven and he was three, 1986, Mom bought him a little blue blazer at Modell’s to wear to our sunrise-timed church service. For me, she designed and sewed a custom two-piece outfit which I quietly pulled on in my dim bedroom, so early that it seemed wrong even to speak aloud. “Get your tie,” I whispered to my brother, referring to the clip-on navy strip of rayon he’d been attaching to his camouflage G.I. Joe t-shirts all week in anticipation.

My dress had a pristine white top with an attached skirt in dove grey, splotched with tropical-style petal pink flowers. The matching pink jacket tied at the neck and had puffy gathers where the sleeves met the shoulders. She finished my look with white flats, patterned white tights, a plasticky woven pink hat, and a patent-leather grey handbag.

39 years later that photo—a consummate image of my childhood self exactly the way my parents saw me then—is on the cover of the book I wrote about my parents.

When we were finally ready to hop in our ten-year-old buttercup yellow Mercury Bobcat station wagon to go to church, sunshine came roaring into our suburban front yard. I whisper-begged Dad to take my photo in the new golden light. We were nearly never this dressed up and nearly never saw the sunrise. I pulled my father and our Kodak point-and-shoot outside through the metal screen door, and he knelt in the dewy grass framing me and our house behind me. I imagined the glamorous, sun-drenched result, which we’d see a week or more later, after the roll was done and the Fotomat returned the prints. As he fussed to find precisely the right shot and the best angle, riotous pre-seven AM sunbeams shot across the yard, and I couldn’t hold my eyes open any longer. I raised a hand and shielded the right side of my face with a flat palm. He clicked the shutter.

39 years later that photo—a consummate image of my childhood self exactly the way my parents saw me then—is on the cover of the book I wrote about my parents.

For years I called this project a “reported history of my parents,” feeling a deep reluctance to call the book what it is, a memoir, and a fervent interest in telling their story, not my own.

When it was time to develop a cover for the book, I found it overwhelming to think of a visual way to complement the text I’d so deeply researched and labored over for years. Capturing all those years and these dynamic individuals in 100,000 words was hard enough; how to identify just one image to signify and communicate it all?

Various paintings and illustrations felt wrong, and I was convinced there wasn’t an existing image of my family that could possibly work. I’d been through all thousand or so family photos I have during the investigative phase of my writing and never saw much of anything except sloppily-composed snapshots. All the different houses where we lived. Our vacations and pets. Random shots of the kitchen counter or a patch of daffodils that meant something to someone, once. In many, my brother and I are comically unhappy-looking. Portions of the years we were growing up were indeed sad and strange, but the story I aimed to tell about those years is spiked with the joy and mystery and love my brother and I felt alongside all the frustration and despair.

Taking another pass through my boxes of polaroids and prints, a dear friend noticed a print of something that felt to me like a throw-away: a poorly-framed and sort of blurry but undeniably cinematic shot of young me in the yard Easter morning. “This one will work,” he emailed me. “It’s authentically you.”

I acknowledge that had my parents lived to see this book, they may have been a little mortified, a little angry.

I am the only person in the photo but the main character here is the sun. It dazzles everything, making the patchy early spring grass appear greener than it would have been, dappling our shingled rust red house with a glamorous glow. The 1975 Mercury shines in the driveway. My outfit is indistinct, but my slight smile is obvious, even as my hand obscures half of my face.

I’d missed it, but seen through someone else’s eyes—someone who has known me well for decades—the photo is an exquisite rendering of the story I hoped to tell. I’m clad in a creation sprung from my mother’s imagination, posed in front of the house where we lived, photographed and art-directed by my dad. Young Amanda is so overwhelmed by the onslaught of the incoming day that I succumb by shielding my eyes. Only the Lord himself could have conjured lighting so dramatic.

“Doesn’t it seem unfair?” another friend asked, speculating about how my forthcoming book could possibly obliterate my relationships with living family members and maybe even ruin my credibility. After all, she reminded me, “Your parents aren’t here to defend themselves.”

I acknowledge that had my parents lived to see this book, they may have been a little mortified, a little angry. I also have a weird confidence that they would have moved through those feelings and ultimately enjoyed the attention. All my years of research brought me a more intimate understanding of my inscrutable mom and dad; they were never terribly ashamed about their shortcomings and would have been pretty chuffed to see themselves memorialized. I told my friend that when she reads it, she’ll see the painstaking work I took to research and report, to be true to who my parents were, according to my newer and deeper grasp of their authentic selves. Or, as true my own faulty lens can ever depict them.

For all my years of insistence that this is a book about my parents, I finally understand that it’s a book about me—specifically about how I saw my parents for all those years. I wanted to immortalize them, but instead I made a 352-page self-portrait. The vulnerability is almost all mine.

I’ve exhorted my brother to write his own book if he ever chooses, and sometimes I wish one or both of my parents had recounted our lives from their perspective. How would they have portrayed their self-defeating choices and desperation? Their bursting and fierce love for each other and for my brother and me? Mom’s hoarding and Dad’s madcap inventions? Their sorrows and achievements and secrets?

If my mom and dad had managed to tell their own story of the raucous and strange 40 years we were a family, how would they have done it? My gut says they’d tell the kind of story that’s enigmatic and moody, a little funny and mysteriously beautiful, that reverberates with the innocence of childhood but is rife with unanswered questions, shot through with golden light and best viewed warily with one eye covered.

__________________________________

Destroy This House is available from Summit Books. Copyright © 2025 by Amanda Uhle.

Amanda Uhle

Amanda Uhle writes about culture, politics, and civil rights for The Washington Post, Politico Magazine, The Boston Globe, and Newsweek. Uhle is coeditor of the I, Witness series of first-person stories by youth activists, former director of the 826michigan youth writing and tutoring program, and cofounder, with Dave Eggers, of the International Congress of Youth Voices. Their work with youth writing organizations worldwide is documented in Unnecessarily Beautiful Spaces for Young Minds on Fire. Uhle is the publisher and executive director of McSweeney’s, an independent nonprofit publisher of distinctive books and magazines.