Always on the Clock: On the Writerly Need to Find Ideas in Unexpected Places

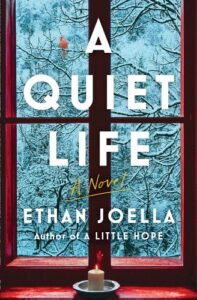

How Ethan Joella Keeps His Brain Awake (at Least a Little Bit)

I read once that when ducks sleep in a big group, those on the outer rim keep one side of their brains awake. This is what it’s like to be a writer, at least in my case. You’re never off the clock. What if you miss overhearing a perfect word from two booths down at the diner? What if someone opens their purse in a waiting room, and random objects spill out: a pair of pantyhose, unicorn-flavored gum? If you are on a walk, and a neighbor’s garage is open, you want to see what they have on their shelves: laundry detergent, potting soil, rock salt. Like the duck on half alert, the writer doesn’t let their guard down.

I can’t switch my brain off from idea collecting. How I wish I could flip the sign like Charlie Brown’s friend Lucy in her psychiatry booth. “The doctor is in,” and I could either be on or off the clock as a writer. But whether I’m awake or dreaming, the writer brain is always active.

In the last week, here are a few things I’ve noticed: the taste of sand because my wife and I went to look at the ocean during a storm and the wind was blowing so hard grains landed on our lips; the way cheap teabags sink and fancy teabags float; the way someone can put on a new shirt and it uplifts their whole mood. I noticed that our cat loves having her closed eyes kissed.

But what do we do with all this random input? What makes its way into a story, and what is needless noticing—moments when I could have just dismissed the word, the sound, the detail away? When is an idea large enough to command a piece of writing?

One day, a couple years ago, my wife and I walked into downtown Rehoboth Beach. It was a perfect fall morning, the sun was on our faces, and the flowerpots in town had cabbage plants and pansies in them. We got to the boardwalk, where a group of old men stood by a taffy shop. We smiled at them, and in the distance we could see the ocean, cold and still, reflecting the light. People were riding bikes or standing by the dune grass, hands in their pockets, just looking at the water. Just as we were in earshot, one of the men said to his friends, “I’m taking my first trip to Florida this year without my wife.” I paused for a minute and looked over. The other men nodded solemnly, and one grabbed his shoulder.

It’s the things you can’t forget about that show up in your writing.

Elizabeth Strout said recently in an interview that even when she was young, she could feel what it was like to be another person. This is how I felt as I looked at that man.

My grandparents used to go to Myrtle Beach every winter, and they looked forward to it more than they did anything else. We grew up in northeastern Pennsylvania, and being snowbirds was something that retired couples aspired to. After that day, I couldn’t stop seeing that man’s gentle face, knowing he was soon making his first trip without the wife who I assumed had died.

If I had had a notebook in my pocket, I would have written down, “trip south without wife.” I could have taken out my phone and jotted it on my Notes app. Instead, I let the idea wash over me, and I thought about what it means to be a couple for many years. I started to see an old man in his home, winter weather outside. What if his wife had just died in the spring and they’d already booked their vacation rental for next year? Would he make that trip without her, or would he stay in his quiet home during January and February, snowstorm after snowstorm, the days cold and unrelenting? I didn’t have an answer to my character’s dilemma.

As a professor of psychology as well as writing, I know we don’t forget things if they’re deeply processed. So I didn’t write it down, but I kept thinking about this idea of moving forward without your spouse. Whenever I thought about what I would be writing if I started something new, I thought about that old man and the trip without the person he loved. I liked not jumping on the idea right away, and turning down the flame, as Ernest Hemingway said, letting it simmer. I didn’t have my in yet. So I sat on it all through winter and spring, but it didn’t leave me.

What we notice can’t all have a starring role, but the taking it in is where it’s at.

That summer, a friend invited me to a writing retreat at her house. We could all come for a couple of hours with our laptops and do prompts or just work quietly on our own stuff. One of the first prompts someone suggested was to use the word towel. We all thought about the word and wrote for ten minutes, and when I envisioned a faded yellow and white striped towel, my character, Chuck, and his wife Cat, came instantly to me. I saw Chuck in his house, and he was holding on to her towel everywhere he went. This towel became one of the central objects of what would be my second novel, A Quiet Life:

She used it for every bath, the towel hanging over the linen closet door to dry afterward, the smell of her pink soap as he walked by. And when they drove those hundreds of miles to Hilton Head every winter, she took the towel along, and it became her beach towel. Even as she got older, there was something alluring about the way she draped that towel around her body, or shook it out over one of the lounge chairs at the pool in South Carolina.

What can he do with this towel now, this towel he should have buried with her, this towel that he sleeps with some nights, this towel that hangs there, that stays wherever he leaves it?

This, the central premise and central object for A Quiet Life, came to me because my writer brain was open and receiving. Had I not been listening—had I not taken my friend up on the opportunity for the writing retreat—the two ideas (the grieving man and the towel) might never have come together. I’m so glad they did.

I have gotten writing ideas from dreams, from a phrase I saw on Twitter, from a group of deer in a clearing as I drove by with the sun going down. You might find something small, like a dog could be wearing a raincoat. Or you might get something bigger like Chuck and the towel, or you might get something that hasn’t found its way anywhere yet—a woman leaving the dollar store with St. Patrick’s Day balloons, a child’s single mitten sitting on top of a gumball machine, a perfect basket of apples, a colleague who found a hermit crab in her back yard and kept it for years. I haven’t written any of these down, but the images have stayed with me.

Some friends of mine carry stylish notebooks in their back pockets or purses. Or some will jot down every idea on their phone throughout the day. I admit that once in a while, especially with a perfect line, I have scrambled to find a piece of paper for that sentence or title idea.

But it’s the things you can’t forget about that show up in your writing. It’s the ideas that don’t go away. Collecting words and images is a worthy exploration. These ideas you gather will become your character’s faded bathing suit, the sound of a moped, the plastic wrap sticking to the cheesecake. It is our job to notice and then show, to have a reader say, That’s right! I do that. That’s me.

Louise Erdrich once said that writers have “an insect-like devotion” when it comes to our craft, and it makes me think of being young and crouching down, noticing bees perched on clover, or fireflies blinking in the blades of grass, or lines of ants and what they carried and where they scuttled off to. Maybe that was my early practice—that attention to the smallest matters of daily life.

We use the methods and tools that work for us. If you keep that part of your brain open like the ducks and let it all flood in, some ideas will be immediately useful or other bits will show up because they are ingrained somewhere. What we notice can’t all have a starring role, but the taking it in is where it’s at. It’s when the good stuff will find you.

Writing is half what you do at the keyboard and half what you do while in line at the post office or while you’re unloading the dishwasher or shaking out your car mats in the driveway. Erdrich is right, and often that’s how I see myself now: a small ant carrying home what I have found while out in the world, hoping it will be useful, keeping it balanced and ready, to help me do the best job.

__________________________________

A Quiet Life by Ethan Joella is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Ethan Joella

Ethan Joella teaches English and psychology at the University of Delaware and specializes in community writing workshops. His work has appeared in River Teeth, The Cimarron Review, The MacGuffin, Delaware Beach Life, and Third Wednesday. He is the author of A Little Hope, which was a Read with Jenna Bonus Selection and A Quiet Life. He lives in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, with his wife and two daughters. His next novel, The Same Bright Stars, will be published in Summer 2024.