Alix Ohlin on How to Map the Shape of Your Short Story

The Author of We Want What We Want Tries to Find the Shape of Things in Alice Munro, Ocean Vuong, and More

In the before times, I loitered in museums. The last show I saw in person before the pandemic was work by David Wojnarowicz, film and photography he made as the AIDS epidemic ravaged. I emerged from the gallery blinking into the grey light of a March afternoon in Vancouver, thinking about loss, memory, and the accompaniment of art.

Shortly thereafter, we went into lockdown, and over the months that followed my mind turned over new pandemics and previous ones, the images of Wojnarowicz I’d seen, and how they represented, as Olivia Laing puts it in in Funny Weather, “defiance in the face of extinction.”

I didn’t write much during that time, but the few stories I drafted all feature bodies under siege, on the verge of disappearance and extinction. In retrospect I can see how the show was continuing to haunt me, and how my own work spoke back to it, filtered through my own experiences and preoccupations.

It’s always been this way for me with the work of visual artists—that it helps me cross some threshold into the space where writing happens. It offers both a refractive lens and a kind a companionship. I respond strongly to the work itself, and the experience of roaming through a gallery or a museum seeds my subconscious. More often than not I come away from an exhibit with a notebook dense with scribblings that connect, intuitively and indirectly rather than explicitly, to the art I’ve just seen.

This is especially true for me with short stories. Perhaps it’s because the short story is where I feel most engaged with questions of form, where I experience writing at its most dynamic and malleable. Sculpture, painting, installations—all of them are encounters with form, and because of how they inhabit physical space, they help me conceptualize forms I might work with myself.

When it comes to form, I’ve never felt at ease with the narrative arc as it was taught to me in high school, the Freytag’s pyramid that leads from inciting incident through rising action to climax and denouement. It doesn’t seem to capture the essence—or the breadth—of the kinds of stories I love or the kinds I’m trying to write. So I’m always seeking out different ways of thinking about story form. In recent years, I’ve found aesthetic resonance in Jane Alison’s exploration of narrative structures like the meander or the spiral. I’ve been intrigued by the use of kishōtenketsu in the work of writers like Ocean Vuong. I’m continually thinking about where my own stories might go, what shapes they might take.

Freytag’s Pyramid doesn’t seem to capture the essence—or the breadth—of the kinds of stories I love or the kinds I’m trying to write.

When I read stories I admire, I’ve found mapping their forms visually to be extremely helpful, similar to the process Martin Solares describes here. For me, story mapping is a kind of reverse outlining that helps me understand the story better, how it progresses and how it’s engineered, and it keeps me attuned to the possibilities inherent in the genre. As Jerome Stern writes in Making Shapely Fiction, a book that also ascribes narrative meaning to visual forms, “These shapes aren’t rules that you follow so much as ways to create.”

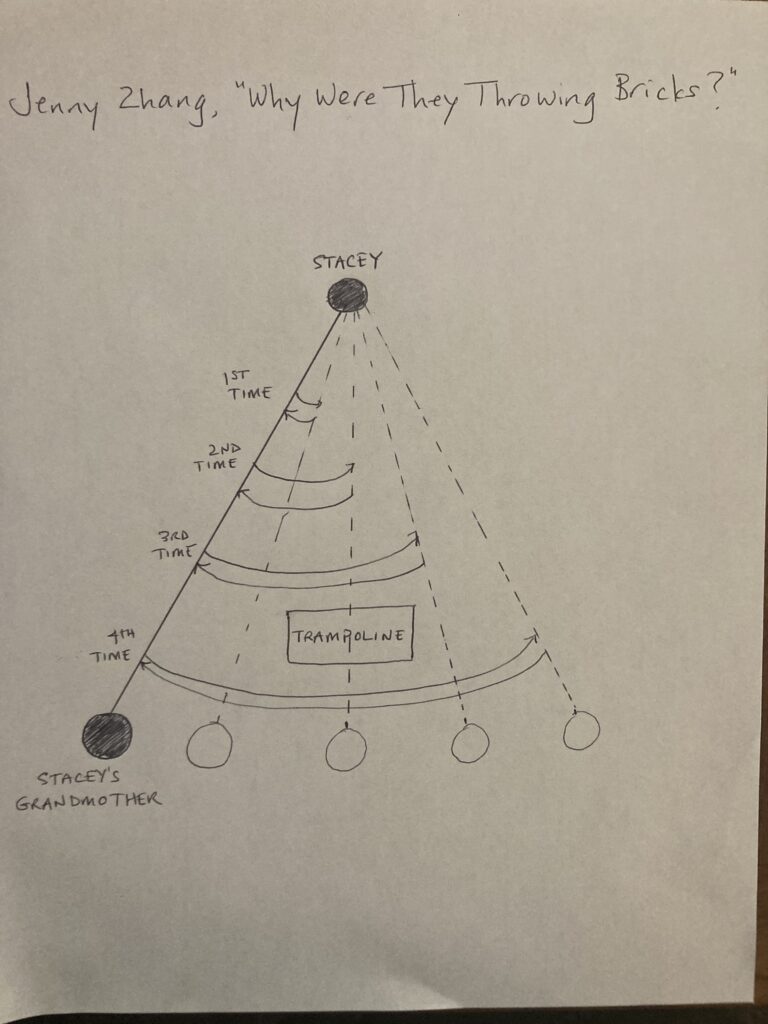

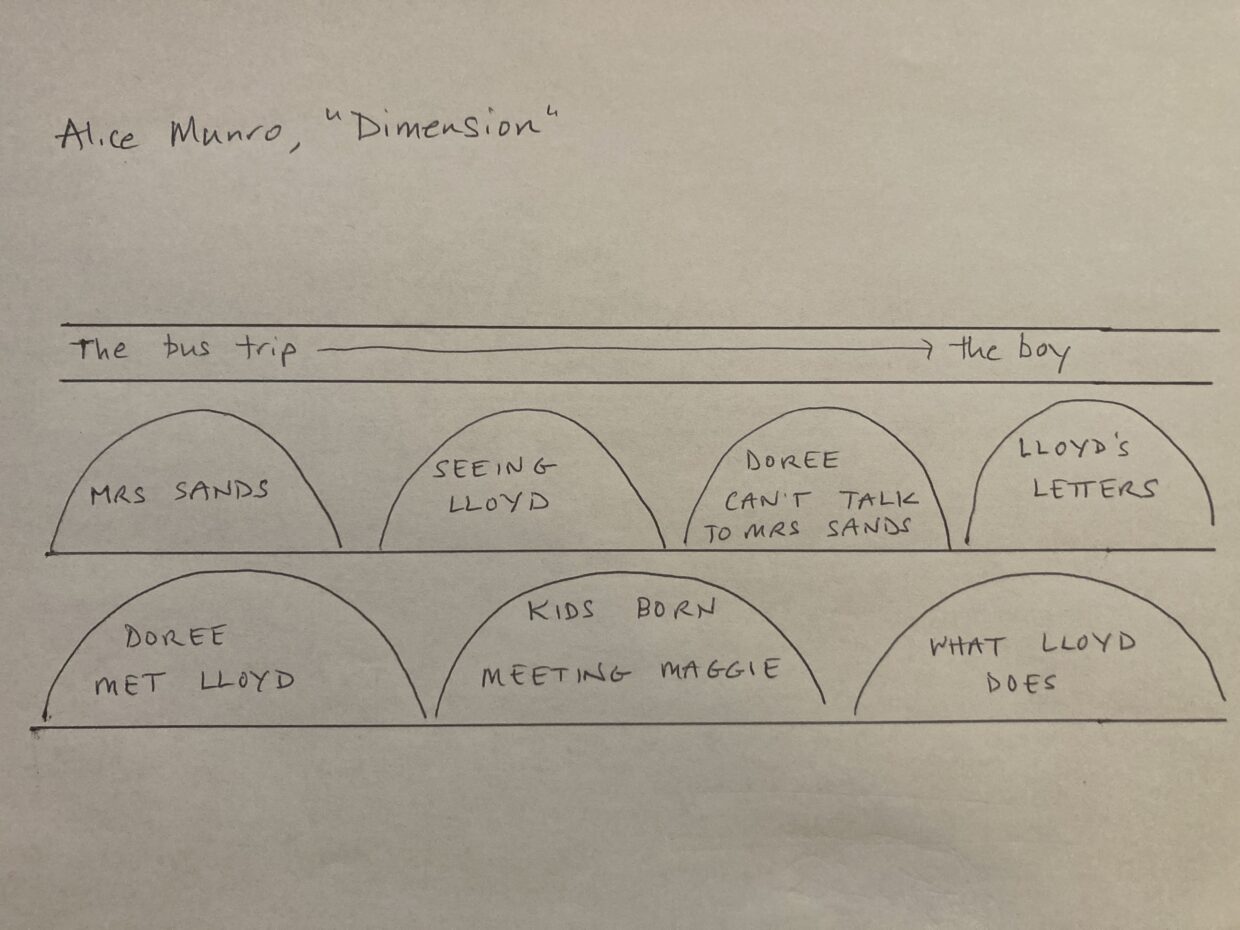

My story maps are personal and idiosyncratic, subjective visions of my own reading experience. When I map Jenny Zhang’s story “Why We Were They Throwing Bricks?” I find a pendulum structure that swings back and forth with dramatic energy. Justin Torres’s “Reverting to a Wild State” has a chiasmic structure that looks like an X to me, two thematic trajectories crossing through space and time. Alice Munro’s “Dimension” is an aqueduct, the present tense story crossing the top, two levels of backstory arching beneath.

Thinking about these forms leads me to consider what internal architectures might support the stories I want to tell. And because I’m thinking about story structure through visual analogies, I return to visual art. And I ask: what if I wrote a story shaped like this sculpture I saw, or with the compositional pattern of that painting? What narrative architecture might emerge?

Some examples, to illustrate what I mean: Julie Mehretu, who had a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney this summer, creates multi-layered, complex abstract paintings and drawings that evoke the dynamics of global capitalism, displacement, and identity. Sarah Sze constructs mixed media installations that look like universes to me, exploring time, space, and perception. I wouldn’t say that my own work directly resembles that of either artist, but their boldness has been galvanizing. Their work has nudged me towards story forms built around networks of power and powerlessness, that (at least in my drafting of them) are engineered as miniature universes. The lives of disparate characters—a Somali-Swedish orphan; a childless North American couple; their teenaged gamer neighbor—are all mapped as intertwining paths in my story “The Universal Particular.” I thought of “Money, Geography, Youth,” a story about a young woman who returns to Los Angeles after a year doing volunteer work in Ghana to discover that her father is engaged to her best friend, as an entropic constellation of needs, clustering the three main characters together even as they drift apart.

The artist Ann Hamilton is interested in trace presences. In her portraits, she places a pinhole camera inside the mouth, making “the orifice of language the orifice of sight.” When the mouth opens, the film is exposed, and the portraits, to me, look blurry and intimate, organic and embodied. I love the idea of dual portraiture as a form, and it fits itself well to my preoccupation with dyads of women, one seen through the eyes of another. What would a story look like if it took the form of a pinhole camera positioned inside the mouth of the taker? Perhaps it could involve a woman who witnesses her long-time friend disappear into her obsession with new age therapies (“The Point of No Return”), while she also contemplates the strange evolution of her own life.

A final example is the work of Janet Cardiff and Georges Muller, themselves highly narrative artists. They create aural environments where you can listen to a story being told as you walk through a given place, whether Edinburgh, the Montreal métro, or Central Park. The way Cardiff and Muller use voice to overlap with landscape, the way headphones enclose you in your own world while you navigate the outside one, has inspired the way I think about first person narration in fiction as both a guide and a barrier, an enclosure and a self-directed universe. In my story “The Detectives,” a woman who knows everyone in her small town still feels deeply alone; in “Service Intelligence” a college student who can’t talk directly about her sexual assault sees criminal activity everywhere. The voice in these stories is meant to speak in your ear as you walk through the world of the characters, keeping you close and cloistered at the same time.

When I’m stuck in the draft of a particular story, I’ll try to draw the map of where I am, what I’ve built so far. If I can’t map it at all, that tells me I might need to take it apart and assemble it a different way. Or perhaps that it’s time for me to go back to the museum and roam around, looking for new forms, new shapes.

_________________________________

Alix Ohlin’s We Want What We Want is available now from Knopf.

Alix Ohlin

Alix Ohlin is the author of six books, including Dual Citizens, which was short-listed for the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Best American Short Stories, and many other places. She lives in Vancouver, where she is the Director of the UBC School of Creative Writing.