About halfway through Alison Bechdel’s new graphic memoir, The Secret to Superhuman Strength, a little-known anecdote from literary history sweeps across an entire page: a field in Cambridge, a beam of sunlight, and underneath it, writer and transcendentalist Margaret Fuller.

It was Thanksgiving in 1831, and Fuller—a prolific intellectual who would eventually co-found The Dial magazine with Ralph Waldo Emerson—had just left a church service, feeling melancholy. Fuller, 21, would soon move with her family from the active academic scene of Cambridge to a rural area, where she would be expected to care for them instead of devoting herself to her work. But that day, as “the sun shone out with that transparent sweetness, like the last smile of a dying lover,” she wrote, the thought came upon her that “there was no self, that selfishness was all folly, and the results of circumstance; that it was only because I thought self real that I suffered.” She would carry the realization with her for the rest of her short life, until her death at 39 in a shipwreck off the coast of Fire Island.

Reading her story more than 150 years later, Bechdel was struck by the memory of a similar revelation she had experienced at the same age (Bechdel’s came after taking psilocybin mushrooms). The freedom of that feeling was a guiding light for Bechdel as she became an ardent gym-goer, hiker, and student of the writers and intellectuals who had sought self-knowledge in the natural world. It would also become a locus of her newest work, which is at once the story of her relationship to physicality, a literary history of exercise, and a tender, funny meditation on interdependence.

Ever since her deftly humorous comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, which began in 1983, brought the stories of a lesbian group of friends to dozens of alternative newspapers around the country—a landmark accomplishment, particularly at a time when publishing gay stories was no easy feat—Bechdel has been a leader in graphic storytelling. After publishing Fun Home (2006) and Are You My Mother? (2012), graphic memoirs that explored her childhood in Pennsylvania and relationship to her parents, she embarked on writing The Secret to Superhuman Strength, which would take her eight years to complete. Reading through the book, it’s easy to see why—this is her most complex work yet. Bechdel structures the book, her first in full color, chronologically, following her relationship to exercise (and media images of it) throughout her life. Along the way, we learn more about the girlfriends that influenced that relationship, her family, and the lineage of writers who looked to nature and movement for personal fulfillment, including Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Jack Kerouac, and Gary Snyder.

And, of course, Fuller, who, for her part, inspired mixed reactions during her lifetime and after (a fate not unheard of for women working in male-dominated circles). Emerson, a close collaborator, wrote that Fuller was “inscrutable,” while Hawthorne, having apparently scrutinized her quite a bit, settled on the label “a great humbug.” Her reception today is no warmer; Judith Thurman noted for The New Yorker in 2013 that while “she is a rock star of women’s-studies programs … a wider public hungry for transgressive heroines (especially those who die tragically) has failed to embrace her.”

Meanwhile, Bechdel, whom I reached by phone while she was on the treadmill at her home in Vermont, told me she’s ready for a Fuller renaissance. We spoke about the thread of literary history in her book, encountering masculinity in popular culture as a lesbian, collaborating with a romantic partner, and why endings are so hard to write.

*

Corinne Segal: Let’s talk about the earlier parts of your book, when you’re describing your first impressions of exercise culture and the videos that you would encounter, the images that you would see, as a child. How did those media experiences shape your early ideas of masculinity?

Alison Bechdel: As a little kid, I started noticing those bodybuilding ads in my comic books: the Charles Atlas ads, the weight-gain drinks, and these big muscle guys, like, kicking sand on the little skinny guys at the beach. I found those fascinating. I was just riveted by those little cartoons and scenes and I always wanted to send away for one of those little books that would tell me how to look like Charles Atlas. It’s kind of weird looking back, because I didn’t really think about those bodies as male bodies, and, you know, that I wasn’t going to grow up to look like that. But as a kid, I really wanted to be big and strong like those guys.

I’m going to have to turn off the treadmill. I’ve got to think too hard for this… I’ll just pace at my own speed.

So those were confusing, those ads, as a kid. I wanted to be strong. I had some kind of slight gender confusion going on; I would look at myself in the mirror and stretch my arms out to the sides and if I stood just right, it would look like I had super broad shoulders like those guys in the comic books. Eventually, I did send away for one of those things that promised “the secret to superhuman strength.” That’s where the title of the book comes from. And it was this very disappointing guide to some martial art that I couldn’t make any sense out of as a little kid.

“I drew a very literal image of me tripping in Central Park, but I don’t think it at all conveys what was happening inside of me.”This was at a time when people were only just starting to exercise. Bodybuilding was this very fringe activity that most people didn’t do, until Jack LaLanne was on television when I was a small child. When I was home from school, I would watch his exercise programs for all the housewives. And he, too, was very muscular, had these big biceps and this tiny little waist. He’d wear this bizarre spandex jumpsuit, which was quite mesmerizing. It was just the beginnings of people really pursuing exercise as a thing.

CS: All of your works, and particularly this book, are full of literary references. This one in particular runs the gamut from the romantic poets to Emerson to Margaret Fuller, Jack Kerouac. What does your reading and research process look like when you’re beginning a project? How do you make those connections?

AB: It’s sort of an organic unfolding process, which is partly why my books seem to take me so long. This book took eight years from the very beginning to the very end. I don’t know what I’m doing going in.

I knew I wanted to write a book that would talk about exercise and all these different activities I’ve done all my life and to use that as a sort of primary source. But I also like to just explore ideas. And I’ve always loved Kerouac’s book The Dharma Bums. I’m not a huge Kerouac fan in general, but there’s something about that book that I just have always really loved, or at least parts of that book, where he’s writing about being outside, being in the Sierras or the Cascades and hiking, talking to his friend Gary Snyder about Zen and the nature of the universe. That was one entry point for me.

Kerouac led me back to the transcendentalists, to Emerson, who was an inspiration for him, and I’d already been a big fan of Margaret Fuller’s and had read this wonderful biography by Megan Marshall about Fuller, so it was cool to learn more about her connection to Emerson. The two of them were very much inspired by the British romantics from 20 or 30 years earlier, Coleridge and Wordsworth, who were also writing about nature. They were hiking and trekking in the hills in England, and the transcendentalists were also walking all over New England here, and Kerouac was walking all over the Sierras. I just really connected with that lineage of people thinking about their place in the world and in the universe and being outside while they were doing it.

CS: Why did you want to explore the connection between Margaret Fuller and Emerson?

AB: As Emerson describes it in Nature, he has this—how does he put it—he’s a “transparent eyeball.” He’s out in nature one day and has this experience suddenly of feeling his self drop away until he sort of merged with the world around him. He described it as feeling like a transparent eyeball.

Margaret Fuller had sort of a mystical experience of being free from her particular self, which also happened outside, one day when she left church in Cambridge and went out to wander around in the fields. And I really connected with both of those experiences because I had one too, although mine was drug-induced—I had taken psilocybin mushrooms one summer day when I was 20, and I felt like I experienced that same absence of self that they were describing. And it was such a remarkable feeling, a really blissful feeling. It’s something that I have always tried to get back in various ways, through exercise, through creativity, through my half-hearted efforts at meditation over the years.

CS: Was there anything particularly challenging about depicting that kind of experience in a graphic memoir? The people that write about them often write about how words sort of elude them when attempting to describe it. Was that something that you encountered?

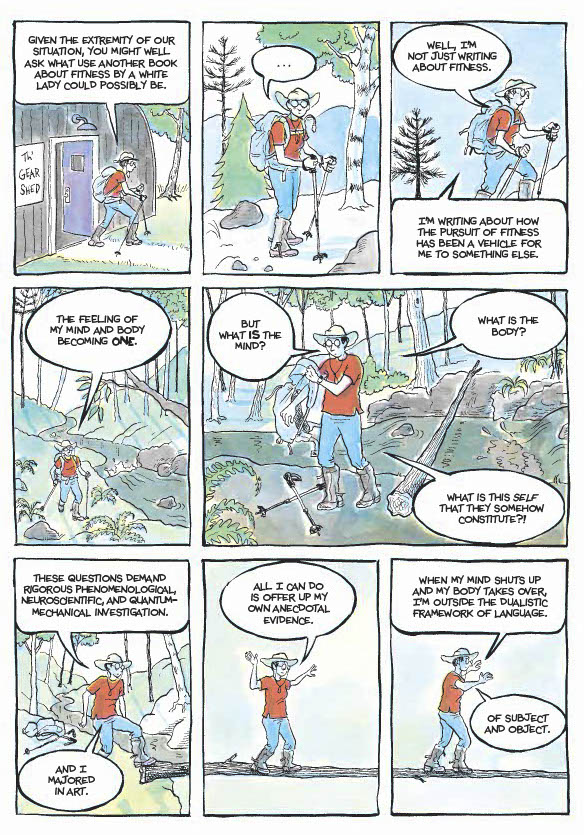

AB: Yeah. I mean, that’s the nature of that sort of mystical experience. It really is beyond language. We live in our everyday lives, in this in this world of language, of subject and object, and the whole thing about getting past yourself is that you’re getting past that dualistic structure. There is no more subjective object. There is no more self and other in that in that weird, exalted state. No, I utterly failed to describe that. Even, you know, I’m trying to illustrate it with drawings and there’s no way to really do that either. I drew a very literal image of me tripping in Central Park, but I don’t think it at all conveys what was happening inside of me.

That was my youthful rebellion, was refusing to read Leaves of Grass.It’s funny because Emerson had a friend, an illustrator, who actually drew the transparent eyeball moment, and it’s like this big eyeball, like the size of a basketball on a pair of legs with a hat on top. It’s very funny-looking, but of course, that cartoon isn’t really illustrating what Emerson was experiencing either, which was his self literally disappearing.

CS: At one point in the book, you write about the process of beginning Fun Home and feeling like you “weren’t a writer.” What was your idea at the time of what it meant to be a writer?

AB: Well, I had this odd experience growing up with two parents who really adulated writers and artists, and they very much encouraged me to become a writer or an artist. And it was kind of an overwhelming pressure. Many people who become artists have the opposite problem—they grew up with parents who don’t care about those things and they have to fight to do them. But I was fighting against my father trying to make me read Walt Whitman. That was my youthful rebellion, was refusing to read Leaves of Grass. I felt like there was something very intrusive about my parents needing that, needing me to do the kind of things they wished they had done.

So I carved out this very different path. I was a creative person, but I found a way to express my creativity that sort of flew under their radar. Comics was something that they didn’t really get, and that was why I liked it. And also, as I became more politicized, I liked the way that comics were a popular art form. You know, they weren’t elitist, like fine art or the kind of literary writing my parents admired. For a long time, I considered myself, you know, a cultural worker, or almost a kind of journalist, and not an artist.

So when I found myself starting to write this book about my dad, even though it was in the form of a comic book, it was going to be a whole book—not a tiny comic strip, but a full-length book. I found myself really struggling with real artistic questions and eventually having to acknowledge to myself that, yeah, I’m writing a book. I’m an artist and a writer, and this is what I’m doing.

CS: I’m interested in hearing more about how you made decisions about color for this book—it has a very different color profile than your other work. You’ve also written that your partner Holly worked on the coloring process, and I would love to hear more about your collaboration.

AB: This is the first book I’ve ever done in color. I’ve never worked very much in color at all because it’s really hard. … I knew that I wanted this book to be full color because it’s so much about life and vitality and exuberance and it seemed crazy to make a book like that black and white or even monochromatic.

I was figuring out a technique that I could do, that I thought would be sort of simple. But then my deadline was crashing down on me and I realized, at a certain point, that there was no way I was going to be able to finish all the drawing for this book and color it in the allotted time span. That was just impossible. And I convinced Holly, my partner, to do this coloring process. She’s an artist, and you just have to know how to use a watercolor brush to color the book. But it was still a very challenging experience for me to collaborate. I’m not used to collaborating. In fact, that’s part of why I’m a cartoonist, is because I’m such a control freak. Cartooning is something that you can control all the levels of yourself, it’s nothing like filmmaking.

It’s a weird process, too. It wasn’t like she was sitting there with watercolors and doing a straightforward painting. She was painting a cyan layer, a magenta layer and a yellow layer for each page. All the colors are complicated combinations of layers. She was painting them all in gray ink, and the color all happened on the computer after she made these endless layers. It was, in many ways a very frustrating process, but I’m very happy with the end result.

CS: That sounds so complicated.

AB: It’s really complicated. I mean, there’s like five or six layers for every page of this 225-page book. Crates of paper.

CS: I wanted to ask you about ending this book, which you discuss in the book itself as a difficult process. Do you often encounter endings as obstacles, or was that specific to this project?

AB: Endings are very confounding for me. Even ending a comic strip when I was just doing like 10-panel cartoons, I would find it hard to end things. I find finality difficult. And I have learned to acknowledge that part of that is, you know, finishing a project is very much like finishing a life. There’s just something really sad about it, and finite, and I don’t want anything to end. In these memoirs I’ve been writing, I do have this odd compulsion to bring them right up to the present moment, the moment at which I finish the book. I felt the need to bring this book up to the very moment at which I finished it, which is some kind of strange high-wire act.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

__________________________________

The Secret to Superhuman Strength by Alison Bechdel is available via HMH Books.