Alia Trabucco Zerán on Writing About Women Who Kill

“Their crimes are a privileged window from which to observe how the very meaning of womanhood has changed over time.”

“Women who kill,” I reply, time and again, when people ask me what my book is about. “I’m researching cases of women who kill.” And each time, as if part of a script, the same scene plays out in front of me. Men and women alike furrow their brows, wince, and then nod their heads in approval of my decision to tackle such a pressing, awful, and all-too-common problem in Latin America.

It’s my turn: the moment when I must correct their mistake, word by word, and watch as their understanding becomes disapproval and suspicion. Where they should have heard the words “women killers,” a strange mental lapse made them hear the opposite: “women who have been killed.”

Once I got over my surprise at this repeated misunderstanding, it actually helped me to realize something fundamental: it’s easier for people to imagine a dead woman than a woman prepared to kill. And it didn’t matter if I said “murderous women” or “violent women.”

By the same slip—more cultural than auditory—the disturbing image of an armed woman was superseded by another, inoffensive one: that of a defenseless woman, six feet under, herself murdered or the victim of violence. “Woman” and “killer” were true antonyms, it seemed—words that, when spoken together, proved unhearable, unthinkable, either causing selective deafness or conjuring the most terrifying flights of fancy: witches, Medea, vampires, femmes fatales.

Incidentally, this mental slip doesn’t happen when we mention “men who kill.” The invisible gender laws operate covertly and constantly, guiding the script of violence toward the same ending. When a man kills, he does not cast doubt on his masculinity, irrespective of his motives or victims, his weapons or circumstances. For a man, the possibility of his violent act is always in the air and even helps confirm his status as a “real man.”

A woman who kills, on the other hand, is twice outside the law: outside both the codified laws and the cultural laws that define and regulate femininity. And it is this double transgression, this twofold rebellion, that triggers that telling slip of the ear. Writing this book, reassessing these emblematic cases of female killers, would mean precisely retraining that ear. Only then can the reverberations of their gunshots be heard.

Their crimes, while disturbing, are a privileged window from which to observe how the very meaning of womanhood has changed over time.

But what made me want to write this book at all? What drove me to lurk in dusty archives, to be repeatedly met with looks of suspicion and fear? Today, as feminists take to the streets to decry the sweeping scale of gender-based violence, the question “why write now about women who kill?” isn’t a trivial one. Some will believe this publication to be an error of judgment, an unnecessary departure just as we slowly begin to shape a fragile awareness of the primary victims of machismo.

There will also be readers who search these pages for a false equivalence between the systematic violence suffered by women and another, statistically exceptional kind. I don’t intend to oblige those readers. My aim is not to minimize the alarming recurrence of femicide, or, much less, to endorse killing as a weapon in the feminist struggle. Women who kill are the exception and it’s better that they remain that way. Why, then, focus on female offenders? What interested me in women who kill?

It’s never easy to pick apart the driving impulse behind a book. Interest, pigheadedness, morbid curiosity, desire, and a rebellious streak are all there in the background when I think about the earliest stages of writing When Women Kill. To this, I could also add an intuition and an anecdote. The former was a suspicion that steered me from the very start, but that only now, at the end of a long and winding journey, can I state with any conviction: remembering “bad” women is also a task of feminism.

And I don’t mean reclaiming wrongly persecuted figures like the witches Silvia Federici rescues from the stakes, or the killjoys Sara Ahmed vindicates as both the most disruptive and the most necessary members at the family dinner table. I’m speaking, rather, of the genuine wrongdoers, proven killers, almost irredeemable beings who are, at the same time, essential to a feminism intent on expanding accepted ideas of what men and women should feel, to include men who no longer base their masculinity on violence and women who are able to express rage without being seen as somehow less human.

The pressure on women to be perfect mothers, exemplary daughters and wives, and successful professionals has reached unsustainable levels. Virginia Woolf’s angel in the house looms overhead, hurling her ruthless demands at us, both inside and outside the home. In today’s world, resisting her call and questioning her intentions is a matter of survival; we must ask the angel why we have to remain sacrificial and passive, silent and servile, and what is so bad about expressing our anger and frustration.

Woolf treacherously proposes to kill her. I propose that the angel go mano a mano with the women killers. I propose that, confronted with the angel’s penetrating gaze, we recover all the antiheroines: the crooks, the convicts, and even those women who picked up a gun, aimed it at their victims, and shot them at point-blank range. In the face of the angel’s vexing demands, I propose we rescue a handful of women killers: strange women who are the antitheses of feminist figures like Simone de Beauvoir or Amanda Labarca, Flora Tristan or Mary Wollstonecraft, but who enable us to see what happens when we fail to meet the expectations that hang, like an invisible guillotine blade, above our heads. Their crimes, while disturbing, are a privileged window from which to observe how the very meaning of womanhood has changed over time.

Their contradictions and failures act as a mirror, reflecting back typically “un-feminine” emotions. And that is why remembering these women, retracing their movements and reconstructing their trials and crime scenes, is so vital for feminism. To see ourselves in them, to see them in us and to speak their names without fear: Corina Rojas, Rosa Faúndez, Carolina Geel, and Teresa Alfaro.

__________________________________

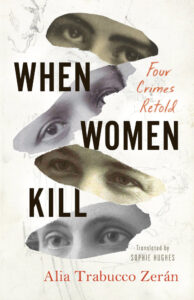

© Alia Trabucco Zerán from When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold, And Other Stories, 2022. When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold is the winner of the 2022 British Academy Book Prize for Global Cultural Understanding. It is translated by Sophie Hughes, and published in the US by Coffee House Press.

Alia Trabucco Zerán

Alia Trabucco Zerán was born in Santiago, Chile, in August 1983. She was awarded a Fulbright scholarship for her MFA in Creative Writing at New York University and holds a PhD in Spanish and Latin American Studies from University College London. Her debut novel The Remainder won the Best Unpublished Literary Work awarded by the Chilean Council for the Arts in 2014, and on publication was chosen by El País as one of its top 10 debuts of 2015. In 2019 it was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize.