Aja Monet on Robin D.G. Kelley and the Ongoing Struggle for Black Liberation

“Sometimes we trip into our past as we endure the present, but freedom is always now.”

When they say literature liberates, surely they were talking about Freedom Dreams.

Maybe it was love, maybe it was their dimples dancing, the way one girl rapped her words around us like a loose hug, our bodies transformed by the rhythm. Or how a few organizers lay in the hammock swaying as another’s guitar dripped in calloused fingers. In the humid honey of June heat, a mango tree open-armed and waving sat deeply rooted in our Little Haiti backyard. This is where a dream became freedom.

Shades of sweat gathered beneath shiny brazen green leaves, the people singing, catching the breeze like a spirit. We were timeless and no longer fighting. A premonition or an image that felt familiar came like a shoulder tap in my heart’s eye. We gathered there to hang and rest after a community organizing meeting. Everyone, for more than a moment, was present and alive and forever. It was sacred ground. We weren’t arguing, we weren’t triggered, we weren’t overwhelmed with grief. A smoke signal of possibility, a place we could feel, touch, and see. I found a new way to write a poem or as Kelley writes, a way to transport us to another place.

I was carved out of the flesh and blood of Black people who breathe poetry.

Where power seeks to obstruct and exploit language, Robin D.G. Kelley creates room for the unlanguagable. This book is a profound testament to the enduring dimension of our imaginations and the poetry of our organizing. Twenty years later, the truths revealed remain relevant and necessary especially in the thick paralyzing despair of a global pandemic. Many are disconnected from one another, a people socialized on social media constantly inundated with gross injustices all over the world and the final frontier of our movements becomes the mind. We are being initiated into the visions of those who have struggled before us: abolition, universal healthcare, global solidarity, and environmental justice. We are the dreaming.

Freedom Dreams is a book that documents and contextualizes the political power of our shamanistic ability to feel and embody medicinal methodologies of how we resist. In the cadence of courage, these words are my belonging; it reflects the life I have made unbeknownst to me, a Blues surrealist poet marooned in the movement for our being. Fueled by the radical movements of those who came before us, Kelley conjures the legacy of Barbara Smith, Jayne Cortez, Aimé Césaire, Queen Mother Moore, Amiri Baraka, Paul Robeson, Sun Ra, and so many others.

We are what we are fighting for. Right now. As we demand presence and awareness, we are the freeing. Who are we without war, poverty, violence, police, and prisons? Who would we be if money wasn’t our concern? If love was our currency, how would we distribute it? How do we value the unseen? I have spent my life traversing the tenses of time, the lettered language of the heart and mind. As our movement is busied by the struggle for our material conditions, I have obsessed over the immaterial needs of our people; poetry is where I’ve gone to meet the edges of myself. To touch the currents and vibrations of our experiences and perceptions. I was carved out of the flesh and blood of Black people who breathe poetry. The pain of being here and nowhere. A cause to live our most intimate lives.

We are the dreaming, an intervention organizing by way of presence. Years later, beneath the same mango tree, I watched Ntozake Shange glow back and forth in an old wicker rocking chair with a cigarette between her polished fingers like a wand. Her smile was an heirloom we all carried close. The Last Poets sipping cold brew flirting with the past, leaning in the groove of now. DJ Rich Medina spinning the soundtrack to a dream manifest conducting light in our hips and hands. The people were fed and full of imagination. Sonia Sanchez lecturing love in our living room with movement lessons. Inspired by the stories of African and Indigenous ancestors who were driven to the swamps and developed sovereign communities during the horror of American slavery, we facilitated a collective of young poets who were also organizers as we created the Maroon Poetry festival in Liberty City, Miami.

I had no idea we were rehearsing for the vision of Kelley’s closing chapter. We built a temporary stage made from wood pallets in Tacolcy Park with aspirations to design a solar-powered amphitheater. Elders and young people together in harmony. The event was free and accessible, healthcare professionals on-site taking blood pressure, healing hands offering massages, morning meditation and yoga, barbers donating their skills to cut the children’s hair. Tire swings roped around our trees, there was a huge flag with a North Star waving above the children’s jungle gym.

We built pop-up libraries, benches decorated with free books. We turned the children’s workroom in the community center into an art gallery with local artists and vintage national Black treasures. We registered community members to vote in the upcoming state election and discussed the local politics of our time. We petitioned our people to help restore voting rights for 1.4 million Floridians who were formerly incarcerated. Huge banners of Emory Douglas posters billowed in the field as he discussed the revolutionary function of art with the people. It was surreal. We were more than our competing identities; we were organized in deep relationships with one another.

Poetry offers us a method and way through the world; how we organize one another shows who and what we are for.

“Surrealism is not some lost, esoteric body of thought longing for academic recognition,” Kelley writes. “It is a living practice and will continue to live as long as we dream. Nor is surrealism some atavistic romanticization of the past. Above all, surrealism considers love and poetry and the imagination powerful social and revolutionary forces, not replacements for organized protest, for marches and sit-ins, for strikes and slowdowns, for matches and spray paint.”

We are one of the many echoes of Robin D.G. Kelley’s words reverberating in the world. We are proof that his vision and argument are not only practical but critical to our movement’s possibility and power. Here we were, The Dream Defenders, supported by a small group of lawyers, the Community Justice Project, workshopping the poetic language for our political vision of another Florida a few years earlier. We called our socialist vision for our people the Freedom Papers. It was an unconscious nod to the emancipation papers given to escaped Africans upon their arrival to the Spanish colony of St. Augustine.

Over 250 years later, we conjured Fort Mose, the first free Black settlement in America, right in our backyard. Except, we defined freedom for ourselves—the freedom to imagine and struggle for alternatives: freedom from police, prisons, and poverty, freedom of movement, freedom of mind, freedom to be, etc. We spent many years using our literal home to facilitate workshops and nurture organizers in the efforts of decolonizing our imaginations. Language and how we use it is crucial to the vision for our lives. Kelley’s book offers us our history so we can create with a clearer vision for our future. Sometimes we trip into our past as we endure the present, but freedom is always now.

While our society is hyper-focused on the technical and material developments of nation states, as we resist the patriarchy of settler colonialism, and the rising sea levels, and forests on fire, and the not enough hospital beds, and the violence of poverty, we must not lose sight of the deep emotional expressions of our heart. We are in a battle of ideas. We are in a battle for our spirits. There have been many developments and evolutions in the mechanics of our technology—Kelley reminds us, every movement demands an evolution and transformation of the heart and mind.

The capacity to dream, to cultivate and facilitate the collective as self-determined visionaries, is how we demand the alternative.

He writes, “By revolution of the mind, I mean not merely a refusal of victim status. I am talking about an unleashing of the mind’s most creative capacities, catalyzed by participation in struggles for change.”

It was not easy at first to convince organizers and movement lawyers how poetry could organize our people into the revolutionary world we want to see, or that dreaming up a vision together was in fact the work we most desperately needed. But as Freedom Dreams demonstrates, we were not the first to struggle and we will not be the last. Poetry offers us a method and way through the world; how we organize one another shows who and what we are for. We used June Jordan’s revolutionary blueprint and focused on the poetry workshop as a way to access and cultivate our radical visions.

Our ability to reenvision and transform our society is what radical social movements are made of. We must return to the root, which is always love. So many of us have become victims of doubt and fear; remembering is our remedy and imagining is our inheritance. It is far more difficult to organize triggered, traumatized, and indifferent people into our liberation struggle. Therefore, our movements must lean on our radical imaginations for the strategy of social poetics to take hold.

Freedom Dreams is a dedication to the continuum. In order to create, we embody what we imagine. Freedom is not illusive. It’s not beyond our reach. It is within our very hands. The capacity to dream, to cultivate and facilitate the collective as self-determined visionaries, is how we demand the alternative. This book is not an answer but an invitation to question; it is a prompt and a road map. Robin D.G. Kelley is a cartographer of a past present future. We are the poem. As we imagine, so we remember.

Where ever we are going

We are there

Whoever we will be

We have been

–Aja Monet, Fall 2021

___________________________________

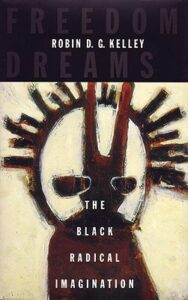

Excerpted from Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination by Robin D.G. Kelley. Copyright © 2022. Available from Beacon Press.

Aja Monet

Born in New York City to parents of Cuban and Jamaican descent and raised in the Brooklyn neighborhood of East New York, Aja Monet Bacquie began writing poems when she was eight or nine years old. At 19, Monet became the youngest winner of Nuyorican Poets Café’s Grand Slam. She later earned her Bachelor of Arts from Sarah Lawrence College and MFA in Creative Writing from the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. Not long after graduation, she published two chapbooks: The Black Unicorn Sings (2010) and Inner-City Cyborgs and Ciphers(2014). Both were later released as e-books. Monet also co-edited and arranged the spoken-word collection Chorus: A Literary Mixtape (2012) with Saul Williams and writer and actress Dufflyn Lammers.