After Steve Jobs, The Flood: Apple Without Its Emblematic and Enigmatic Founder

Tripp Mickle Explains the Line of Succession at a Silicon Valley Powerhouse

Jony Ive steeled himself outside the stately two-story home in Palo Alto. It was early Tuesday morning, October 4, 2011, and a storm system shrouded Silicon Valley’s usually sunny flatlands with heavy clouds. In better circumstances, Ive would have been arriving in Cupertino. Apple was hosting a special event there that day to introduce a new iPhone that he had designed. Instead, he was skipping the show to see his boss, friend, and spiritual partner, Steve Jobs.

Ive entered a house that had become a hospital. Doctors and nurses shuffled around inside where Jobs, sick with pancreatic cancer, was confined to bed. In the study-turned-bedroom where he lay, a TV was wired to provide the world’s only video stream of Apple’s product event, a private screening for Apple’s longtime showman.

Visiting the home weighed heavily on Ive. Since Jobs had gone on medical leave at the start of the year, he had continued to summon Ive and other leaders from Apple’s design, software, hardware, and marketing teams to the house. Inside, the passing of time could be measured by the CEO’s weight loss and diminished movement. His face had grown gaunt, and his legs had atrophied into rigid branches. He seldom left the bed where he was surrounded by photographs of family, prescription bottles, stacks of paper, monitors, and machines. Still he refused to stop working.

“Apple’s not a job for me,” he would tell them. “It’s part of my life. I love this stuff.”

Jobs was the ultimate showman. Cook was not.

On that day, as Ive headed for the room where Jobs lay, he passed an image by the photographer Harold Edgerton, the man who froze time. The photograph showed a red apple suspended against a space-blue background the instant after it had been shot by a bullet, exploding its core.

*

About fifteen miles away, Tim Cook pulled into the asphalt parking lot outside Apple’s headquarters at 1 Infinite Loop. The company’s thirty-two-acre campus, a ring of six off-white buildings, was located in Cupertino, just off Interstate 280 and behind BJ’s Restaurant and Brewhouse, a national chain and an unassuming base of operation for a company racking up yearly profits of nearly $26 billion.

It was perhaps the most important Tuesday of Cook’s career. Two months earlier, Jobs had elevated him from chief operating officer to chief executive officer. The timing of the promotion had caught the world by surprise. Apple and Jobs had concealed the severity of Jobs’s illness and deprived staff, investors, and the media of insight into his deteriorating health. When he ceded power to his longtime lieutenant, he assured employees and investors that he would remain involved in product development and corporate strategy but said that Cook would lead the business, a position that thrust the company’s back-office manager to the forefront of its product release events.

In a few hours, about three hundred journalists and special guests would descend on Apple’s campus for Cook’s first keynote address. Such events were usually held in large auditoriums or convention centers in San Francisco, but this one was being hosted in a cramped lecture room known as Town Hall on the back side of its campus. Apple’s showrunners had chosen the small venue, close to home, intentionally. Jobs was the ultimate showman. Cook was not.

Apple’s cofounder had turned corporate presentations into product theater, winding up the audience with carefully crafted stories that framed the purpose of a new device with a simplicity that excited potential customers and fueled sales. He had hyped the iPhone as being three things: a phone, a music player, and an internet communication device. He had turned the slender MacBook Air into a silver rabbit so thin it could be pulled out of a brown office envelope. And he had persuaded the world that iPods weren’t about playing songs but about changing the way people discovered and enjoyed music. Cook was more comfortable evaluating supply chain logistics than standing in front of an audience. When he had taken the stage at previous events, it had been in a secondary role to detail the number of computers sold or stores opened. But with Apple’s leading man ill, the time had come for Cook, the understudy, to step into a starring role.

With Apple’s leading man ill, the time had come for Cook, the understudy, to step into a starring role.

Holding the meeting in Town Hall reduced the risks of Cook’s debut. The venue was the equivalent of Off Broadway, with fewer seats for journalists and critics who might pen bad reviews. It was also on campus, so Cook had been able to walk over to the venue from his office throughout the week for repeated rehearsals. He had spent hours going through his scripted remarks in a bid to become desensitized to potential stage fright. The size of the venue meant that there were fewer cameras, a smaller crew, and less noise. The familiarity of the surroundings focused his attention on the most important task: delivering his lines.

*

Staff nicknamed the phone coming out that day “For Steve.”

Over the past three decades, Jobs had cemented his place as a man of such original vision that he had drawn comparisons to both Leonardo da Vinci and Thomas Edison. Working from his parents’ ranch home in Los Altos, California, he and his friend Steve Wozniak, a self-taught engineer, developed one of the first computers for the masses, a gray box with a keyboard and power supply that could display graphics. In 1977, their company became formally incorporated as Apple Computer Inc., a name inspired by Jobs’s favorite band, the Beatles, and their record label, Apple Records.

Jobs’s brazen salesmanship of their computers was dismissed by some as all pitch, no substance, but the Apple II computer became one of the first commercially successful PCs, earning the company $117 million in annual sales before it went public in 1980. It made Jobs and Wozniak millionaires and secured their place in Silicon Valley mythology with a rags-to-riches tale that had begun in a garage.

Apple’s most ardent customers were as fervent about and protective of the company as members of a religious cult.

A masterful marketer with an eye for design, Jobs redefined the PC category in 1984 with the Macintosh, a computer for the masses that could be controlled by the click of a mouse rather than by pecking on a keyboard. He pitched it as a machine that would democratize technology and dethrone the largest computer maker, IBM. Working with the advertising agency Chiat/Day, he developed an Orwellian Super Bowl spot titled “1984” that cast the Macintosh and Apple as a sledgehammer-wielding Olympic sprinter who shatters a giant screen projecting Big Brother.

He unveiled the computer a week later at one of Apple’s first signature events, captivating the audience in a darkened auditorium in Cupertino by turning the computer on and allowing it to speak for itself, saying, “Hello, I’m Macintosh. It sure is great to get out of that bag.”

But a sales slump in 1985 led the board to oust Jobs in favor of John Sculley, a former PepsiCo executive. Sculley pushed Apple to new sales heights until Microsoft’s Windows software began whittling away at Apple’s market share. The company was a late entrant to the laptop market, and infighting led to Sculley’s ouster. His successor, Michael Spindler, who joined the company in 1993, flooded the market with Apple computers, a strategy that only deepened its woes. The company lost nearly $2 billion in two years and was on the cusp of bankruptcy in 1996 when it struck a deal to buy a desktop computer company called NeXT that Jobs had launched while in exile.

Jobs returned to Apple and ignited one of the most remarkable business comebacks in history. He culled its product lineup, used NeXT’s operating system as the foundation of OS X, a faster, more modern software system, and spearheaded the development of a translucent, candy-colored desktop called the iMac that returned the company to sales growth.

He then pushed Apple beyond computers into consumer electronics with the iPod, which came out in 2001 and put thousands of ninety-nine-cent songs into people’s pockets. The iPhone followed in 2007, introducing a touch-screen system that changed communication and became one of the best-selling products in history. Its successor, the iPad, which came out in 2010, redefined tablet computing. The string of product successes turned Jobs into a cult hero.

[Jobs] was so convincing that some believed he might even outlive death.

Apple’s most ardent customers were as fervent about and protective of the company as members of a religious cult. Some tattooed its corporate logo or advertising phrases onto their wrists. As CEO, Jobs assumed an almost messianic hold over them, and his daily uniform—a black turtleneck, Levi’s 501 jeans, and New Balance sneakers—added to his ecclesiastical bearing. He could distort reality. He refused to accept limits in engineering or manufacturing that might impede one of his ideas, and he could persuade his team of designers and engineers that they could achieve what seemed impossible. He was so convincing that some believed he might even outlive death.

*

Though Jobs hadn’t attended rehearsals ahead of that day’s event, some of Apple’s leadership arrived at Town Hall that morning wondering: Will he show up?

Staff saved an aisle seat at the front of the lecture room for him, draping a black piece of cloth with the word Reserved in white over the back of a tan-colored chair. Apple’s general counsel, Bruce Sewell, who sat in the adjacent seat, knew that the odds were against Jobs filling it. Jobs’s health had worsened in recent days, but he had surprised everyone before and even some of his closest advisers had not given up hope that the empty seat would be filled by the time the event began.

As the group huddled, they were gripped by fear: either Jobs didn’t like the event and wanted to chew them out, or his health had worsened.

The lights were low when Tim Cook slipped into the front of the room from behind a dark screen with a white Apple logo. His thin lips formed a flat grin as a few people applauded politely. In a Brooks Brothers spin on Jobs’s casual and fashionable Issey Miyake turtleneck, Cook wore a black broadcloth button-down shirt and spun a presentation remote in his hands as he paced in front of the crowd.

“Good morning,” he said. “This is my first product launch since being named CEO. I’m sure you didn’t know that.”

He smirked, hoping that his dry humor would take some tension out of the room. A strained chuckle rippled through the audience. Though the joke hadn’t landed, Cook pushed forward. “I love Apple,” he said. “I consider it the privilege of a lifetime to have worked here for almost fourteen years, and I am very excited about this new role.” His voice grew confident as he shifted his focus to Apple’s growing retail business. The company had just opened two amazing stores in China, he said. The one in Shanghai had set a record by welcoming a hundred thousand visitors in its first weekend, a total that Apple’s flagship store in Los Angeles had taken a month to achieve after its debut. Cook transitioned to business highlights from Apple’s Mac, iPod, iPhone, and iPad products, complete with line graphs and pie charts. “I’m pleased to tell you this morning that we have passed the quarter of a billion unit sales mark,” he said. “Today, we’re taking it to the next level!”

Cook ceded the stage to Jobs’s other top lieutenants. Mobile software chief Scott Forstall detailed new messaging capabilities, services head Eddy Cue followed with a demonstration of iCloud, and marketing chief Phil Schiller revealed the iPhone 4S, which featured longer battery life and a better camera but looked like its predecessor. The event culminated with Forstall doing a live demonstration of Apple’s new virtual assistant, Siri, that with the push of a button and a vocal question pulled up the weather, showed stock prices, and listed nearby Greek restaurants.

[Jobs] wouldn’t be reprimanding them. He wanted to say goodbye.

“It’s pretty incredible, isn’t it?” Cook asked as he reclaimed the stage. “Only Apple could make such amazing hardware, software, and services and bring them together in such a powerful yet integrated experience.”

His enthusiasm failed to win over the hardened tech press. The journalists and technology analysts in the audience were unimpressed. One technology analyst told the Wall Street Journal that the presentation had been “underwhelming.” Another expressed disappointment that Apple had stuck with a 3.5-inch iPhone screen instead of pushing it to 4 inches. Fans grumbled on Twitter. Investors dumped shares, sending Apple’s stock price down as much as 5 percent and erasing billions of dollars in market value. It was a box-office rejection.

Cook and the rest of Apple’s leadership had no time to process the public reaction. As the event ended, Jobs’s wife, Laurene, texted some of his top lieutenants—Cook, Phil Schiller, Eddy Cue, and Katie Cotton, the vice president of worldwide communications—to say they should come to the house. As the group huddled, they were gripped by fear: either Jobs didn’t like the event and wanted to chew them out, or his health had worsened.

They sped to the house, some fifteen minutes away, hopeful that Jobs’s wrath awaited. It was easier to imagine him angry than process their unspoken despair that his health had prevented him from attending.

When they arrived at the Tudor-style home, Jony Ive had already departed after spending time alone with Jobs that morning. Laurene told the parade of business executives that Jobs was doing poorly and wanted to speak with each of them individually. He wouldn’t be reprimanding them. He wanted to say goodbye.

*

The following afternoon, October 5, 2011, a symphony of notification dings rang across Infinite Loop. An alert appeared atop Apple employees’ iPhones, delivering the news “Steven P. Jobs, Apple co-founder, dead at 56.”

___________________________________

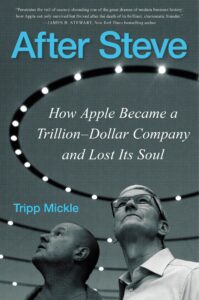

Excerpted from After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul by Tripp Mickle. Copyright © 2022. Available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Tripp Mickle

Tripp Mickle is a technology reporter for The New York Times covering Apple. He previously covered the company for the Wall Street Journal, where he also wrote about Google and other Silicon Valley giants. He has appeared on CNBC and NPR, and previously worked as a sportswriter. He lives with his wife and German shorthaired pointer in San Francisco.