After Hiroshima and Nagasaki: How Allied Media Reported on the Atomic Bombs’ Devastation

An Oral History of the Coverage What the United States Attempted to Cover Up

In the months after the end of the war, the US went to great lengths to cover up the truth about what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and hide the horror from the American people. Even while the rough enormous casualty figures were public, the specifics of the destruction and the experiences of those in Hiroshima and Nagasaki emerged only slowly. Japanese-American correspondent Leslie Nakashima, who had spent the war in Japan, traveled to Hiroshima in late August to search for his mother and filed a dispatch with United Press on August 27, 1945, that was the first widespread report about the scale of devastation.

Leslie Nakashima, correspondent, United Press: That the atomic bomb, more than Russia’s entry into the war, compelled Japan to surrender as she did on August 15 instead of waging a showdown battle on the Japanese mainland is a justifiable conclusion drawn after one sees what used to be Hiroshima city. I’ve just returned to Tokyo from that city, which was destroyed at one stroke by a single atomic bomb thrown by a super flying fortress on the morning of August 6. There’s not a single building standing intact in the city—until recently of 300,000 population. The death toll is expected to reach 100,000 with people continuing to die daily from burns suffered from the bomb’s ultra-violet rays.

*

On Friday, August 31, 1945, a brief version of Nakashima’s story ran in The New York Times with an editor’s note appended: “United States scientists say that the atomic bomb will not have lingering after-effects in a devastated area.” Below, on page four of the newspaper in the same column, a short story datelined Oak Ridge, TN, announced “Japanese Reports Doubted.”

New York Times brief: Japanese reports of deaths from radioactive effects of atomic bombing are pure propaganda in the opinion of Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves, commanding general of the Manhattan District. Studies by scientists in this country do not bear out the death reports, General Groves said at a press conference here today. “The atomic bomb is not an inhuman weapon,” General Groves told workers and military personnel in a surprise visit to the project yesterday. “I think our best answer to anyone who doubts this is that we did not start the war, and if they don’t like the way we ended it, to remember who started it,” he said.

*

In early September 1945, Australian correspondent Wilfred Burchett was the first outside newsman to make it to Hiroshima.

Wilfred Burchett, article, “The Atomic Plague,” Daily Express, September 5, 1945: In Hiroshima, 30 days after the first atomic bomb destroyed the city and shook the world, people are still dying, mysteriously and horribly—people who were uninjured by the cataclysm—from an unknown something which I can only describe as atomic plague.

Hiroshima does not look like a bombed city. It looks as if a monster steamroller had passed over it and squashed it out of existence. I write these facts as dispassionately as I can in the hope that they will act as a warning to the world. In this first testing ground of the atomic bomb I have seen the most terrible and frightening desolation in four years of war. It makes a blitzed Pacific island seem like an Eden. The damage is far greater than photographs can show. When you arrive in Hiroshima you can look around and for 25, perhaps 30, square miles you can hardly see a building. It gives you an empty feeling in the stomach to see such man made devastation.

My nose detected a peculiar odour unlike anything I have ever smelled before. It is something like sulphur, but not quite. I could smell it when I passed a fire that was still smouldering, or at a spot where they were still recovering bodies from the wreckage. But I could also smell it where everything was still deserted. They believe it is given off by the poisonous gas still issuing from the earth soaked with radioactivity released by the split uranium atom. And so the people of Hiroshima today are walking through the forlorn desolation of their once proud city with gauze masks over their mouths and noses.

George Weller, correspondent, Chicago Daily News: I entered Nagasaki on September 6, 1945, as the first free westerner to do so after the end of the war. When I walked out of Nagasaki’s roofless railroad station, I saw a city frizzled like a baked apple, crusted black. I saw the long, crumpled skeleton of the Mitsubishi electrical motor and ship fitting plant, a framework blasted clean of its flesh by the lazy-falling missile floating under a parachute. Along the blistered boulevards the shadows of fallen telegraph poles were branded upright on buildings, the signature of the ray stamped in huge ideograms.

In the battered corridors of these hospitals, already eroded by man’s normal suffering, there was no sorrowful horde. The wards were filled. There was no private place left to die. Consequently the dying were sitting up crosslegged against the walls, holding sad little court with their families, answering their tender questions with the mild, consenting indifference of those whose future is cancelled. The atomic bomb’s peculiar “disease,” uncured because it is untreated and untreated because it is undiagnosed, is still snatching away lives here. Men, women and children with no outward marks of injury are dying daily in hospitals, some after having walked around for three or four weeks thinking they have escaped. The doctors here have every modern medicament, but candidly confessed that the answer to the malady is beyond them. Their patients, though their skins are whole, are simply passing away under their eyes.

*

While Weller’s report from Nagasaki never made it past the US censor—and was ultimately lost for decades—Burchett’s story created a stir, and a few days later, in an effort to combat the worrisome reporting, US military and Manhattan Project leaders spoke with William Laurence, now back at his post at The New York Times, to downplay the fears of radiation.

Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves, quoted by William Laurence in The New York Times, September 12, 1945: The Japanese claim that people died from radiations. If this is true, the number was very small. Any deaths from gamma rays were due to those emitted during the explosion, not the radiations present afterward. While many people were killed, many lives were saved, particularly American lives. It ended the war sooner. It was the final punch that knocked them out.

*

Within days, the US government sent out a notice to US editors asking them to restrict further reporting on the bomb and its effects in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and to submit further articles to the War Department for review as an issue of “the highest national security” to avoid details of the bomb becoming public. In Japan, the US occupation run by Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP) Gen. Douglas MacArthur set even stricter ground rules.

In the battered corridors of these hospitals, already eroded by man’s normal suffering, there was no sorrowful horde. The wards were filled. There was no private place left to die.

Dr. Tatsuichiro Akizuki: As one of the major policies of General Douglas MacArthur’s occupation, Japan was placed under a press code. The reasons for this were to preserve the peace under the allied occupation and to protect military security and the secrets of the atomic bomb. The occupation was afraid of the criticism that would be directed at the United States if the story of the tremendous cruelty of the atomic bomb were to become known in Japan and throughout the world.

Hideo Matsuno: Because of censorship orders from the military and the post war occupation government, articles couldn’t be written directly from the information collected by reporters. We couldn’t write articles detailing the misery. They just didn’t permit us to write pieces describing too much of the atrocity. Instead, there were articles that justified the atomic bomb, saying it was inevitable. Even on the anniversary of the bombing, at first, we couldn’t even provide extensive coverage on that day. The bomb was dropped on the northern part of Nagasaki in the Christian District. So people in the central part of the city tended to think that this was something that had nothing to do with them—they just wanted to forget everything bad that had happened as quickly as possible. The ruins of the Urakami Catholic Church were cleared right away.

*

It was only in 1946 that New Yorker correspondent John Hersey traveled to Hiroshima and explored the wreckage and the tales of survivors in detail; the result of his reporting ran as a 30,000-word article that took up the magazine’s entire issue in late August 1946. Hailed as an instant masterpiece, the magazine sold out on newsstands in minutes and was read aloud in its entirety on national radio.

Editors’ Note, The New Yorker, August 31, 1946: The New Yorker this week devotes its entire editorial space to an article on the almost complete obliteration of a city by one atomic bomb, and what happened to the people of that city. It does so in the conviction that few of us have yet comprehended the all but incredible destructive power of this weapon, and that everyone might well take time to consider the implications of its use.

John Hersey, article, “Hiroshima,” The New Yorker, August 31, 1946: A hundred thousand people were killed by the atomic bomb, and these six were among the survivors. They still wonder why they lived when so many others died. Each of them counts many small items of chance or volition—a step taken in time, a decision to go indoors, catching one streetcar instead of the next—that spared him. And now each knows that in the act of survival he lived a dozen lives and saw more death than he ever thought he would see. At the time, none of them knew anything.

Lewis Gannett, literary critic, New York Herald Tribune, August 29, 1946: When headlines say a hundred thousand people are killed, whether in battle, by earthquake, flood, or atom bomb, the human mind refuses to react to mathematics. You swallowed statistics, gasped in awe, and, turning away to discuss the price of lamb chops, forgot. But if you read what Mr. Hersey writes, you won’t forget. Mr. Hersey is the first writer to tell about Hiroshima with his feet on the ground, dusty with the ashes of atomized Hiroshima.

_________________________________________

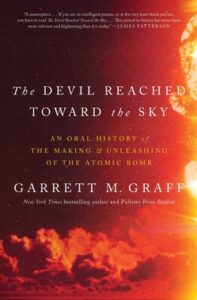

From The Devil Reached Toward the Sky: An Oral History of the Making and Unleashing of the Atomic Bomb by Garrett M. Graff. Copyright © 2025. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Garrett M. Graff

Garrett M. Graff has spent nearly two decades covering politics, technology, and national security. The former editor of Politico and contributor to Wired and CNN, he’s written for publications from Esquire to Rolling Stone to The New York Times, and today serves as the director of the cyber initiative at the Aspen Institute. Graff is the author of multiple books, including the FBI history The Threat Matrix, Raven Rock (about the government’s Cold War Doomsday plans), When the Sea Came Alive (an oral history of D-Day), and the New York Times bestsellers The Only Plane in the Sky and Watergate, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History.