After Freedom, Then What? What Those Escaping Slavery Found in Boston

Jacqueline Jones on the Economic Struggles of the Formerly Enslaved

One day in mid-March, 1856, an enslaved woman named Rebecca Robinson Jones and her three daughters, ages six to nine, stepped off a Norfolk, Virginia, dock and onto the deck of a schooner captained by Alfred Fountain. Unlike many other fugitives, the twenty-eight-year-old mother wore no disguise, and she boldly ushered the children onto the boat with her. Later, William Still, an Underground Railroad conductor in Philadelphia, remembered that she “firmly resolved to be the slave of no master, nor to allow her three interesting children to grow up in slavery.”

Jones’s decision to rely on Captain Fountain carried its own risks; he was well known to Norfolk authorities as a committed abolitionist who had transported many runaways to freedom in the North. The November before, he had bluffed his way out of a tough spot with the Norfolk mayor, who, together with a “posse of officers,” had boarded Fountain’s vessel in search of stowaways.

In a show of bravado, the captain seized an axe and vigorously began to chop a hole in his own deck, a ploy to convince the startled onlookers that no one was secreted below. Satisfied, the mayor and his entourage departed the ship, and Fountain sailed off, with twenty-one men and women hidden underneath a cargo of wheat stowed in the hold.

The quest for freedom was a serious business, with cash changing hands several times over.

William Still considered Jones an uncommonly courageous woman—“a true-born heroine”—and, tellingly, once in Boston she kept her name and found a job right away. Back in Norfolk, her owner offered a $150 reward for her and her daughters. Yet it took a great deal more than raw courage to escape by water from the Virginia Peninsula; it took money. The quest for freedom was a serious business, with cash changing hands several times over. Jones had used the services of Norfolk’s mysterious Dr. Harry Lundy, sometimes identified as a doctor and sometimes as a dentist. An illiterate free person of color, Lundy employed a scribe who took care of his correspondence and forged papers.

The routine charge per clandestine passenger was $25 (about $800 in today’s money); most of those who availed themselves of Lundy’s services were men who had hired themselves out or otherwise earned enough to afford passage. Lundy kept some of the fee and paid his helper, and Captain Fountain received a share as well. On board, members of the crew might demand an additional fee (a bribe), pushing the price of liberty even higher. Still, Lundy was a miracle-worker for those determined to journey to Boston and for those Bostonians who wanted to bring loved ones north.

Once safely in the Bay State, Rebecca had probably relied on help from Mark DeMortie, a shoemaker and one of Lundy’s former employees, who had settled in Boston four years before the siblings’ arrival. Born in Norfolk in 1829 to Haitian Francophone parents (it is unclear whether he was born enslaved or free), DeMortie had worked for Lundy for several years, probably beginning in 1848, and took credit for helping twenty-two people reach freedom.

He traveled to Boston and back with some regularity, consulting with fugitive assistants about the financing of upcoming rescues. Sometime in 1851 or 1852, the young man wrote a letter on behalf of an enslaved woman who was hoping to join her brother in Boston; but, as he later recalled, the letter was “intercepted by her so called master, and I had to resort to the same means to make my own escape as I had sent the poor slaves.”

Virginia-born Peter Randolph was also able to supplement his income by boarding runaways, though it is uncertain whether he and Amelia lost or made money or broke even in the process. In January 1854 the BVC paid Randolph $51 to hide three men, who eventually made their way to Canada. In fact, the business of assisting fugitives proved to be a lively and varied enterprise. Lewis Hayden got paid for distributing handbills warning of slave-catchers and for boarding fugitives, and he was reimbursed for covering funerals of children who died, as well as for the carriage fare he paid for fugitives to go on to points north and west.

Other assistants were paid for clothing, food, and fuel they provided for people on the run. Antislavery ship captains received compensation as well: Austin Bearse, for example, for monitoring incoming ships in Boston Harbor, and Alfred Fountain for transporting enslaved people from the South to New York City or Boston (up to $100 per passenger). Fugitive assistance was both a moral calling and a business, though a business that provided very few with a full-time livelihood.

*

Samuel May Jr. and other white abolitionists scrutinized fugitives and recent southern migrants and assessed their willingness to work in Boston; yet these whites rarely factored into their “experiment” the trauma suffered by men and women who fled from slavery and made their way north. To expect the refugees to find a job immediately upon arriving in Boston was to ignore the tremendous emotional and physical residues of slavery and flight itself.

The passage between slavery and freedom was an ordeal from which many might never fully recover.

Many fugitives made the decision to escape after they had endured some sort of horrific physical or emotional abuse or the threat of it. In recounting their last days in slavery, they described vicious beatings, floggings, and shootings, the fear that they or family members were about to be sold, or the reality of such separations. A goodly number started out on a surreptitious journey only to be caught and dragged back to their owners, slaveholders who had no compunction about maiming, selling, or even killing those captured that they might serve as examples to others.

Even for successful runaways, the journey north, by sea or land, held its own terrors. Once aboard ship, most fugitives had to remain hidden. Squeezed into the hold during what could turn out to be a weeks-long voyage, sweltering or freezing, depending on the weather; concealed somewhere in or among the ship’s cargo, whether on top of a pile of logs or in a hole cut in a bale of cotton; immobilized next to a steamer’s boiler, where the heat and coal dust were almost unbearable, many runaways arrived at the Boston docks wounded, physically ill, and shaken to the core.

One woman stowaway who kept her child in her arms for seven straight days, relying on the ship’s cook to feed them both, disembarked nearly paralyzed. For seventy-five days Clarissa Davis hid in a “miserable coop” in Portsmouth, Virginia, hoping for a rainstorm that would reduce visibility and also the number of people on the docks, which might give her a chance to sneak aboard a steamship in the harbor. She reached Massachusetts safely after traveling in a wooden box on board the packet City of Richmond. Those who traveled by foot suffered from hunger, frostbitten feet, and exhaustion, not to mention the constant fear they would be discovered. Some dared to earn money along the way, working for a farmer in his fields or for a ship’s engineer in the fire room, always looking over their shoulder.

In his flight from rural Maryland, Frederick Douglass disguised himself as a seaman and traveled by foot, train, ferry, steamboat, and stagecoach—seven legs in all, before reaching New Bedford. The passage between slavery and freedom was an ordeal from which many might never fully recover.

Responding to the demands for payment from brokers, dock-workers, crew members, and captains—not all of them imbued with lofty abolitionist principles—some fugitives had to pay up to $100 for a safe escape, leaving them penniless when they finally arrived on free soil.

To expect the refugees to find a job immediately upon arriving in Boston was to ignore the tremendous emotional and physical residues of slavery and flight itself.

Unremitting toil was the hallmark of enslavement, and fugitives and migrants generally understood that wage earning represented the next and necessary step on the way to safety and independence in the North. Baltimore’s William Howard noted, “I expected to work for a living, go where I would. I could not be stopped from working.” In certain respects, the transition from dock work in Richmond to dock work in Boston was not a difficult one. The same could be said for the jobs of gardeners and porters.

However, fugitives skilled in plantation work—blacksmiths, coopers, carpenters—rarely found the same jobs in Boston. Nor did formerly enslaved hostlers, carriage drivers, or teamsters always secure employment working with horses. Upon his arrival in Boston, Peter Randolph, who had been a blacksmith, became a janitor and a tender.

*

An unknown number of fugitives filled the ranks of dock-workers and waiters in Boston. Harvey Parker, proprietor of his eponymous restaurant in a cellar on Court Square, offered his downtown clientele “breakfasts, dinners and suppers at all hours of the day and evening.” Two waiters targeted by federal marshals soon after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act were serving customers at Parker’s. Formerly enslaved house servants might work at the elaborate banquets sponsored by fraternal groups and city authorities. The largest hotel dining rooms seated up to two hundred guests at a time and catered to tourists, who expected Black men to serve them their gin slings and mint juleps as well as their food.

The siblings Harriet and John S. Jacobs had to make a living while keeping an eye out for their owner or his agent. Abandoning the lecture circuit after canvassing upstate New York in the late 1840s, John moved to Rochester, where he worked on The North Star and opened his own oyster restaurant. When that venture failed, he and his sister went back to New York City, but before long he was on his way to the West Coast.

Meanwhile, Harriet spent her days anxiously scanning the newspapers to see which white southerners had taken up residence in local hotels. In June 1851 John was working in California, prospecting for gold but, according to Harriet, by October he “came out poorer than when he went in,” despite moving from the mines to the “dry diggings,” riverbeds of gravel. The end of 1852 found him once again in dire financial straits. He took off for Australia, where gold had been discovered the year before. William Cooper Nell wrote that he “hope[d] John will be lucky in Australia—how richly he deserves success.”

__________________________________

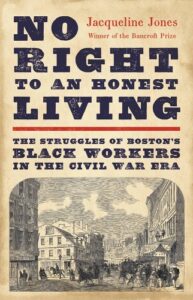

Excerpted from No Right to an Honest Living: The Struggles of Boston’s Black Workers in the Civil War Era by Jacqueline Jones. Copyright © 2023. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Jacqueline Jones

Jacqueline Jones is the Ellen C. Temple Professor of Women’s History Emerita at the University of Texas at Austin and the past president of the American Historical Association. Winner of the Bancroft Prize for Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow and a two-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, she lives in Concord, Massachusetts.