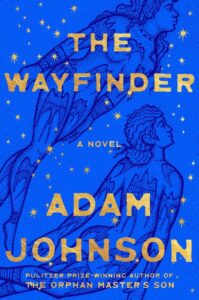

Adam Johnson on Writing a Novel of Ancient Polynesia

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of “The Wayfinder”

Adam Johnson is a rare literary genius. He’s written a Pulitzer Prize winning novel set in a nightmarish Orwellian North Korea (The Orphan Master’s Son), a National Book Award short story collection (Fortune Smiles) that includes one of my favorite short stories ever, “Nirvana,” about “love in the time of drones and holograms,” and now he’s created a 700-plus page saga set in the South Pacific’s Polynesian islands a thousand years ago, during the reign of the Tu‘itonga, the “King of Tonga.” This new novel pulled me under and separated me from our chaotic twentieth-century “world.” I carried it everywhere, to appointments (it’s a heavy book), coffee shops, eager to read on. My sense of time changed. I was swept away by The Wayfinder. How did you conceive this novel? I asked Johnson via email. How long did it take to research and write?

“The Wayfinder was a great pleasure to write, especially the joys of depicting a time of rich and resplendent nature,” he noted. “It was also very rewarding to be so immersed in such rich cultures and environments. Every morning for many years I would move from my dreams to the coffee maker to ancient Tonga, where I would live in a world without our technologies, problems, politics and concerns. That’s not to say that my characters don’t face many challenges, including some of the exact ones we face today, like resource scarcity, depletions and conflict. But by recontextualizing our problems, I felt that they were legible and understandable.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How did you choose the title, The Wayfinder?

This work transformed me and healed me of many modern maladies. Meditating my way into the natural world, as a daily practice, was quite restorative.

Adam Johnson: Celestial navigation is central to the novel. While you or I might look at the ocean and see it as something that separates islands, the Polynesians saw these vast bodies of water as highways connecting the many peoples of the Pacific. In that regard navigation was a sacred and powerful skill, one that took years to learn and much devotion to acquire.

JC: Your central characters are from two families. The heroic young girl Korero is descended from Aoteora (New Zealand) refugees, who are living on a sparse island that doesn’t draw attention from invaders. Hers is a culture of struggle and scarcity (people were eating “grubs and seagrass and boiled bark”). The Tu ‘itonga oversees warriors who take resources from other islands, “depopulate” villages, enslave people; he decides which islands will starve, whose tombstones get stolen. Yet the king hides this violence from his three sons. His oldest is being groomed to succeed him. The second oldest is being trained as a navigator, the third son as a poet. And there is the Tamaha, an all-powerful woman, the King’s aunt, who is the keeper of the Life-Affecting Fan. How did you develop these characters? Are they based on historic figures?

AJ: As the Pacific became populated, a scenario repeated itself over and over. A new island would be discovered. This island would be rich in natural resources. These resources would allow people to settle, to form communities and for their populations to boom. But over exploitation often followed, leading to depletions and extinctions. This struggle for resources often led to destabilization, conflict and displacements. Those who knew how to navigate could set sail for new islands. The people left behind, however, would be faced with difficult choices: taking other people’s resources or learning to live within one’s means. Both options came with challenges and sacrifices.

My novel focuses on two families with teenagers. In one family, the daughter is beginning to ask tough questions about their sacrifices and struggles. In the other, the teenage boys are becoming aware that their comforts come at the expense of others. As a father, this question of how and when to broach difficult topics with my children was ever-present. Should I awaken them to the challenges that put pressure on our communities, like climate change or social inequalities? Or was it my duty to protect my children’s innocence as long as possible? This novel is a repository for those pressing questions.

JC: The island of Manumotu, where Korero is raised, has a non-warlike approach. The idea is to resolve conflict with dialogue, at worst a duel, not warfare. Women are treated with more respect and dignity. Is there such a culture? How has it fared?

AJ: Kōrero’s society is based on the Moriori of Rēkohu Island. Having fled many conflicts on Aotearoa, the Moriori adopted a social code known as Nunuku’s Law, which established a society of non-violence, communal decision making and resource management. I think we could all take some lessons from the Moriori people. (Except for the part where they all died.)

JC: When did you first visit this area of the Pacific? How much time did you spend in the islands of Tonga? How did that shape your storytelling?

AJ: While I’ve visited many of the islands I depict in The Wayfinder, the novel is set before western contact, in a time before clocks, compasses and calendars, when life was measured in seasons and generations and where the oral tradition was sacrosanct. So, in truth, these were places I could only truly visit in my imagination.

JC: How did this story speak to your own family and heritage?

AK: Part of my family is Lakota, from the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota. There were many disruptions in the family line, however, so there are missing stories and inheritances. I feel like I’ve written my entire life to respond to missing stories; while in my real life, they are painful, in my creative life, they are the source of much of my inspiration and creative urge.

JC: One central point for the narrative is the arrival of a comet that appears only once in one’s lifetime. Is this based on a “real” comet?

AJ: Yes, it’s based on a real comet, whose longest recorded passing over the earth came in the period when my character’s peoples most likely would have come into contact. I don’t want to name the comet or the year it passed, because those names and measurements come out of a Western tradition. What mattered to me is what the comet meant in Polynesian mythologies.

JC: How did you come by the poems (and the English translations) included throughout? What does poetry mean to your characters?

AJ: The oral tradition was everything while I was writing The Wayfinder. My first step was to forget the word “novel,” which has a Western tradition and conventions. I immersed myself in Tongan mythology and oral tradition, determined to be a storyteller sharing an epic tale, not a “novelist.” In researching Tongan oral expression, it was clear that poetry and dance were as important to the transfer of cultural tradition as storytelling. That made poetry and dance central to this book. There’s a wonderful chapter in which an older woman extolls a younger one to tell a painful story not with words, but with movements, so as to expel her pain without enlisting narrative’s power to summon, and thus force a re-living, of painful events.

JC: What sort of archival materials gave you details about the characteristics of each of the islands you focus on?

AJ: This is perhaps a continuation of the previous question. Of course, the early witnesses to Tongan culture were the agents of its disruption and diminution. Inherently, a writer doing historical research is always victim to this horrible irony. One of the earliest missionaries to Tonga was a man named Collocott, who, even as he actively diminished Tongan culture in favor of Christian practices, nonetheless was fascinated by Tongan culture and made it his life’s work to document the very things he was helping to disappear. This irony was something I encountered repeatedly. Missionaries in Samoa, Fiji, Tonga and Tahiti found themselves wholly transfixed by the cultural practices they were helping to extinguish as pagan.

Still, such men recorded the poems, songs, myths, stories and place names of Tonga, and without such records, the stories of (mythical? Historical?) figures like The Tamahā, Tui Ha‘atala and Vava‘u Lolonga might have become completely lost. Such is the difficulty of oral history to breech the gulf of a Western religious narrative. When I would visit Tongan islands, I’d ask locals the Tongan names of certain stars and whether they’d heard of local legends. I was much saddened by how much had been lost. One of my guides, Noah, took me from island to island, and he used Google maps on his cell phone, like anybody else. Why wouldn’t he? Another of my guides seemed ashamed, it seemed to me, that he could only give the Tongan names of two constellations: Toloa and Ha‘amonga ‘a Maui, what we would call the Southern Cross and Orion’s Belt.

JC: Your descriptions of seafaring are intense. Did you travel on double-hulled canoes? Study celestial navigation? And learn to map the tides, the winds, the sea swells, as the navigators do?

AJ: I spent every day for ten years amid the tides, the winds and the tremendous, trembling southern swells!

JC: Literally?

In studying a world lacking a Western perspective, I was shocked by how much knowledge and practical technology we’ve forgotten.

AJ: Well, that’s complicated. Oahu’s Bishop Museum has a planetarium specifically set up to teach celestial navigation. That was invaluable. And I read every book on the topic I could find. I tried to get on the Hōkūle’a, helmed by Hawai’i’s Nainoa Thompson, but we couldn’t find a leg and a date that would work with their schedule. Which was my great loss. So, no, the only double-hulled sailing I did was in my imagination.

JC: How did you gather information about the fauna and flora, the medicinal herbs and spiritual practices that are so central to your story?

AJ: Many experts donated years of their time and decades of expertise to help me make these depictions as rich and accurate as possible. Vasalua Jenner-Helu of Tonga’s ‘Atenisi Institute helped with the language, culture and history of Tonga. She also helped translate the poetry in this volume and proved an invaluable resource in every regard. I’m also indebted to the University of Hawai‘i’s Arthur Whistler for his expertise on the medicinal botanicals of Samoa and Tonga. Over and over, Art gifted me with his deep knowledge of Pacific flora and volunteered anecdotes of his extensive sociological fieldwork. University of the South Pacific’s Paul Geraghty provided much-needed assistance with the Fijian language and the dialects of the Lau Islands. His facility with pre-contact Polynesian lexicons helped me navigate many complex linguistic decisions.

JC: You include as a character Koki, a feisty parrot who quotes poetry, and knows the ancient Tongan canon. At one point you have a passage from the point of view of the moon. The sky, the ocean, the natural world dominate the landscape. Time feels different. How did your perspective change while working on this book?

AJ: Any book that takes a decade to write will naturally find the author a different person upon its conclusion. But I can confidently say that this work transformed me and healed me of many modern maladies. Meditating my way into the natural world, as a daily practice, was quite restorative. And imagining a world without our complexities and maladies was spirit expanding. I made many discoveries along the way. If I shared one, it would be this: we think that in our modern and advanced age, we know very much. In studying a world lacking a Western perspective, I was shocked by how much knowledge and practical technology we’ve forgotten.

JC: What are you working on now/next? Another novel? Short stories? Both?

AJ: Yes, I’m absolutely in the thrall of a new novel!

JC: Enough said?

AJ: I like to let narratives take me into worlds that are inaccessible without literary fiction. My new novel does just that. I’ll just say that my new book does not take place on the planet earth!

__________________________________

The Wayfinder by Adam Johnson is available from MCD/FSG, a division of Macmillan.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.