Ada Limón on Kanye West, Womanhood, Truth in Poetry, and More

The Author Of The Carrying in Conversation with Steph Opitz

In 2016, I had the opportunity to meet and introduce Ada Limón for an event at Sam Houston University in Huntsville, Texas. Ada was on a National Book Award Finalist tour celebrating her poetry collection Bright Dead Things. I had written out my own introduction, so I knew what I was going to say, and had practiced it, but I still managed to tear up when introducing her. I’ve jokingly mentioned this instance to others in the Ada-hive, an anecdote about how emotional I feel about her. But they don’t really laugh, because they get it.

It’s hard for me, as someone who’s enthusiastic but inarticulate about poetry, to say technically what is great about Ada’s work. It’s similar to wine; I don’t have a sommelier’s toolkit, but I know what I like. And, honestly, I’m not that interested in telling professed poetry people why her work is good. I’m here to tell you, person who doesn’t see themselves as a poetry-person, you: there is something special here.

I’m not going to say it’s “accessible,” although it is, and I guess I just did, but it’s more visceral than that. I read her work and I feel it in my gut to be the truth; that someone is saying something to me. Maybe it’s because her latest collection The Carrying deals so much with the body that I’m inclined to point towards my own self as a reason I know. Better yet, I know Ada is saying something to me because of her ability to write about wearing sweatpants as a way to say “I love you,” or about driving past road kill as a way to convey “I’m scared of infertility.” Or, best, it’s her way of telling the reader to pay attention, to be alive, to notice the multitudes.

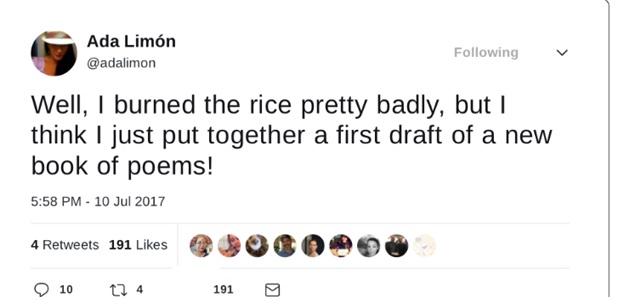

Whatever the case, I’m shouting from the rooftops my love for her work, and was overjoyed to correspond with her over the past month in an email exchange about Kanye West, burnt rice, and womanhood.

–Steph Opitz

Steph Opitz: I’ve heard through what must’ve been an adult version of the game telephone—unless it’s true—that Kanye West somehow inspired you to become a poet? Tell me everything.

Ada Limón: So, this is truly bizarre; that must have been one messed up, hallucinogenic-laden game of telephone. I’ve never been a fan of Kanye West. He’s never really inspired me to do anything except maybe ignore twitter for a while. I’m trying to think how that would have started? Me=inspired by the landscape of West Coast? Me=inspired by 60s and 70s soul music and an old album of whale songs? Me=inspired by creek water and ancestors and Purple Rain and poems written for the Labrador? I hate to ruin the rumor, but alas I’m more inspired by Odetta and Janis Joplin and trees than Kanye.

SO: The story I heard, that I can’t quite piece together, had something to do with a Conde Nast party, maybe Yeezy was there? Not necessarily Kanye West fandom. What a weird thing to hear. Ha.

Let’s get meatier then? From an outside perspective, it seems like The Carrying came out very quickly. This might have something to do with social media giving your fans access to information via tweets like:

Which made me think, wow, she is cranking this out! Did it come together at a different type of pace than previous work? I guess what I’d ultimately like to know is two part: (1) the above question about pace and process, and (2) the sharing of your progress with the general public and how that impacts your work (does it give you accountability, bravery, or something else entirely)?

AL: Question 1:

Wow, you have an incredible memory. I cannot believe I forgot that story. I literally had no idea what you were talking about, but now I remember. It’s not so much that Kanye West inspired me to become a poet, but rather he is partially responsible for my drive to leave New York and write full time. I was working as the Copy Director for GQ Magazine at the time and we were having this super swanky VIP party and Kanye West was playing. Everyone was dressed up and the evening was all signature cocktails and little black dresses. I have this memory of him playing to a very select small crowd and everyone loving it while I was sitting outside sitting on lip of a large cement planter crying a little because I was ready to leave New York. I was so aware that someone else would really love this life I was given, but all I wanted to do was go home to Sonoma, CA and stare out the window, get a dog, and write poems. Three years later I did some version of just that. That night was a shift though. I wasn’t happy and I knew I needed to make a change. I started making a plan, putting away some money, and figuring out how to make a different life. I go back to New York all the time, and I still look back and love the time I spent in the New York publishing world, but every day I get up and know that I’m dedicated to my own words is a good day. Even without the fancy parties and the super stars.

Question 2:

Part 1: I don’t know if I wrote this book fast or slow. I don’t know if I have a sense of my own pacing or progress. I only write one poem at a time and I don’t think about a book until I see it really coming together. Over the last four years I’ve been writing the poems in this book. Because I was dealing with some minor health issues, the poems came in fits and starts, when I was feeling well I wrote a lot, when I was sick, I just napped and read and watched movies. Toward the end of last spring and the beginning of last summer I saw it coming together. It started to have a momentum all its own. And I started to get nervous. When I start to get nervous, I know something real is happening. So that tweet where I burned the rice (rice is so tricky when you don’t set a timer and space out in to poemland!) is from the moment that the draft was really ready to send to my first readers. I couldn’t believe it, but it felt done. The truth is the book hasn’t really been written any faster than any others, but it’s being published faster than my previous books. Milkweed Editions has been really wonderful and from the very start they’ve thrown their support into this book. They are the ones that have fast tracked this book into being and I am so lucky and honored for that.

Part two of your question—I do think that sharing my progress and process with other readers and writers is really helpful. It does make it feel accountable and it makes me very aware that I am not writing into a void. So I want to be, with each poem, trying to get better, to do something different. I want to get better and better every day that I’m writing and growing older. That’s where the real joy is, when you can see that you’ve grown as an artist, as a person, and created something that matters to you. I hope it matters to those readers who pick up the book too, since they’ve spurred me a long!

SO: I’m glad we found the mystery behind the Kanye connection!

You mentioned trying to get better as a poet, trying to do something different. Do you feel like your responsibilities as a poet have changed over the course of your career so far? Like, what are you doing with this book that you might not have felt you could do with earlier collections?

AL: I think any writer worth their salt is always trying to get better, trying to push out of their own comfort zones. I know that we are told we write the same poems over and over, but I am always trying to make those poems exciting for me as the writer. I think, in my earlier collections, I was more interested in more formal constraints, deep imagery, and exploration of thematic connections. I was also interested in what a poem could do: Could it tell a fictional story of a marriage falling apart? Could it use rivers and water themes as a way to cast spells and heal the self? I am still interested in those things, but I am also interested in getting at a truth that might otherwise go unsaid. I suppose what’s different now is that I feel a visceral urgency to write something true. Of course I want to focus on the musicality of the line, the work of the metaphor, the thematic resonance, but above all, I am interested in writing something that matters.

“I was so aware that someone else would really love this life I was given, but all I wanted to do was go home to Sonoma, CA and stare out the window, get a dog, and write poems. Three years later I did some version of just that.”

SO: Since you brought up getting at truth: can you talk about the difference (or not) between getting at what’s true and what it means to tell your own personal story through poetry? I think, as often happens with fiction, too, that readers conflate a general truth with a personal truth (I do this, despite my best instincts), but this book seems to deal with a lot of personal truth, maybe more so than previous collections. . . so, do I, as a reader, get to think this is all you and your truth? And, what does that mean in our relationship as reader and writer?

AL: I love the way you ask this question, because it can be hard with poems. There is a danger in assuming anything is autobiographical or conflating the speaker with the author. But in this case the truths are both personal and poetical. I don’t know when I started letting go of poems that obscured the speaker/author relationship, but somehow I did and, for better or for worse, here I am exposed and cautious for anyone to see. With these last two books—Bright Dead Things and The Carrying—I’ve been doing a lot of mining of the self in order to figure out how I fit in to the world, how I can live. And in that mining, the process of questioning, I hope I have also been able to come at a universal truth. But these poems do, in fact, begin with my life, my body, my mess of unfiltered emotional ongoingness and that material are the bones of the poems. The poems themselves, however, always feel larger than me. They flesh out into real other beings and walk around in the world without me. They grab the keys off the table and tell me not to wait up.

SO: There seems to suddenly be a much wider conversation happening in literature about womanhood, especially as it pertains to motherhood. The Carrying helps broaden the thinking of what it means to be a woman, redefining what it means to be a mother, while discussing your own difficulties of trying to have a baby. 1. Thank you. 2. Can you talk about the process of putting your experience into your art? And if there were other writers or artists that you drew inspiration from.

AL: You know, I am glad you asked this. I have to say, when I was going through fertility treatments I was experiencing so many different physical and emotional responses to the medications and procedures that I kept thinking, why don’t women talk about this more, this is absolute insane? I am lucky in the fact that being a mother wasn’t essential to how I viewed my future, and my husband was happy either way things worked out. But those ups and downs were so wild that I couldn’t help but write about them. I think I started writing about them as just a way of working through some of my own thoughts about the surreal quality of it all, then poem by poem, I realized I was writing a book. I think about Frida Kahlo’s more graphic paintings that were like ex-votos about her physical health and how even though I wasn’t painting or drawing, I was writing as a way of recovering too.

I also was inspired by the honesty and complexity of Maggie Nelson’s Argonauts and Marie Howe’s Magdalene and the poems in Lucille Clifton’s Collected. I’m attracted to the idea of complexity and capacity in creative work. Especially in the work of women. For so long there seemed like there were only two options: motherhood or spinster. How entirely untrue. How banal. How damaging and wrong. We are so much more than any singular limiting archetypal bullshit. The idea that even the physical body holds so much at one time, we have a great surge of complicated thoughts within us at every moment, a fluidity of multiplicities and I wanted to honor that.

“I’ve been doing a lot of mining of the self in order to figure out how I fit in to the world, how I can live. And in that mining, the process of questioning, I hope I have also been able to come at a universal truth.”

SO: You also handle the complexities of what American-ness looks like and/or how we talk about it. Most overtly, I think, in “A New National Anthem” and “The Contract Says: We’d like the Conversation to be Bilingual” but it’s there throughout the collection and your larger body of work. I feel like there’s a suggestion that writers are becoming more political, do you agree?

AL: I don’t know if we are getting more political or if people are just paying closer attention. I do think that it’s a time where everything feels connected. It’s impossible to talk about injustice at the work place without also talking about systemic white supremacy and heteronormativity and ableism. The concept of intersectionality isn’t new for writers and poets, it’s where we live. We live in the liminal spaces where things are connected and where the threads of the universe show up in our hands like life lines. So, I don’t know if we are getting more political or if people are needing poems more so that we are seeing them more places. Poetry is the right place for handling intense political and personal topics because it never has to provide and answer. It has no tidy ending and it’s not a polemic. It’s a place for mess and truth and life and honesty and complication and what’s more political than acknowledging that something doesn’t have an easy answer, and that our contemporary problems are also our historic problems. So maybe we aren’t getting more political, we are getting better at amplifying one another and maybe, just maybe we’re getting a little louder so that we can be heard over all the noise.

SO: What you’re saying reminded me that I saw a survey conducted by the NEA and the US Census Bureau, and recently published by PBS, that said, “28 million American adults read poetry this year—the highest percentage of poetry readership in more than 15 years…Young adults and certain racial ethnic groups account for a large portion of the increase.”

I think that must be a tangible result of the amplification you’re talking about. Can you talk about positive ways folks can amplify each other, how readers can amplify voices they love, maybe you have a specific example?

AL: Yes! I was heartened by that study and it confirmed what I had already witnessed and experienced in my wider community. Part of what makes poetry an art form that’s growing is that the currency of poetry is the single poem. You can send one poem, share one poem on a social media platform and people will immediately interact with those words. It’s a powerful experience and something that’s more difficult to do with long form writing.

I often share poems or even just lines of poem that move me or that I need at that moment. And I read poems that people post often immediately. In that way we are becoming our own curators. We can amplify diverse and important voices that we love and share the groundbreaking poems of the past—legacy poems—that broke open doors. I love reading and writing books, but the fact that the currency of poetry is one poem will always be true and there’s something rather magical about that “one poem at a time” sharing that takes place.

Steph Opitz

Steph Opitz is the founding director of the Loft Literary Center’s Wordplay, a book festival happening in Minneapolis May 2019. For more info please visit loftwordplay.org. She currently serves as a judge for Book of the Month club, as an advisory board member for Wordstock Literary Festival, and on the After Party committee for the National Book Foundation, National Book Awards. Steph was the books reviewer for Marie Claire magazine for six years, and her reviews can also be found in Garden & Gun, Departures, Kirkus, and elsewhere.