Aching for the American Dream: On Writing the Delicate Stories of Immigrant and Refugee Students

Elly Fishman on What It Means to Earn the Trust of Her Teenage Subjects

When I first walked through the hallways of Roger C. Sullivan High School on the North Side of Chicago, I found myself surrounded by flags from around the globe and a swirl of languages—Arabic, Swahili, Spanish—as students crowded the space during passing periods. Groups of girls in hijabs linked arms as they greeted one another, their headscarves paired with bright red lips and leopard-print jackets. Boys quickly formed packs that followed a choreography marked by the sounds of their red Nikes squeaking against the linoleum floor. Above them, the walls were painted with quotes like Maya Lin’s “The American Dream is being able to follow your calling” and one from Dr. Seuss: “Think left and think right and think low and think high. Oh, the thinks you can think up if only you try!”

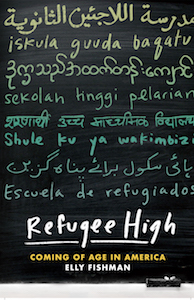

For a century, Sullivan has been a home to immigrant and refugee students; more than 70 percent of the students speak a second language, and over half of the students are either in, or have graduated from, an ELL program. In recent years, during the worst global refugee crisis in history, its immigrant population has numbered close to 300—nearly half the student body—and many are refugees new to the country. These young people come from 35 different countries, speaking among themselves more than three dozen languages. One nickname for Sullivan is the Google Translate School. I spent three years there, reporting what would become my book, Refugee High: Coming of Age in America. During that time, I found myself wrapped up in the students’ stories. Many were young refugees who had experienced immense hardship, but they were also your typical teenagers whose lives were a swirl of Rihanna, acne, and gossip mixed with Turkish pop, midday prayer, hijabs, and bottle-blonde hair.

As I started, though, I was acutely aware that many of these students had suffered years of horror that they often kept inside. Telling their stories would require building trust and understanding over a long period of time.

I started by being a fly on the wall. I spent quite a lot of time in the classroom and in the library, which, at Sullivan, functions as the unofficial English Language Learner lounge. One teacher put me in the “hot seat,” where students could ask me questions; in exchange, I’d answer and toss them a piece of candy. I also held several informal lunchtime circles where we’d push a few desks together and share stories about ourselves. Over time, I began to get a sense of who was interested in my project and who felt comfortable sharing their experiences. This project would be a long-term commitment for both the students and me.

*

Mariah, a sophomore and refugee from Basra, Iraq who arrived in the United States at ten, was one of the first students I met in the library. Like many students new to Sullivan, she spent a lot of time there. During busy lunch periods, Mariah was surrounded by groups of girls who would pose for Instagram posts, decorating their hijabs with puppy ears and flower crowns. Pairs of boys, who, despite speaking different languages, hovered over replays of the recent Real Madrid match, shouting and guffawing at every play. Mariah, like me, observed it all.

Mariah may have been new, but she wasn’t reserved. She never hesitated to offer her opinion on the events unfolding around her. There’s little at Sullivan that Mariah doesn’t care about or weigh in on. I eventually came to understand that this was her version of school spirit.

Mariah soon started seeking me out in the library. We discussed Riverdale plot lines and top 40 songs. We analyzed YouTube makeup tutorials and what makes Auntie Anne’s pretzel bites so dang delicious. This is how I approached building relationships with every student I encountered. Rather than push a microphone in their face, I first wanted to understand how they moved through the world.

But the stories of young people are particularly delicate, and I did not include anything in the book that might put a student at risk. I also changed the students’ names in the book because I wanted them to decide whether to identify themselves.

Over time, Mariah began to sprinkle in stories about her life in Basra. She didn’t remember much, but the memories that remained were sharp and vivid. She recalled walking down the street with her eldest sister and fearing the outdoor shower. For months, she told me about her struggle balancing her parents’ traditional expectations and her ache for autonomy and the American mainstream. She kept mentioning a “really bad” episode that ended in a weeklong stay in a hospital psychiatric ward, but always stopped short of the details.

While I knew living with trauma was a central part of many of their lives, I never wanted to suggest that trauma defined their experience.

Then, one day, nearly a year into my reporting, she told me an especially harrowing and heartbreaking story. What I heard was a story of a young person who felt lost, confused, and like they had nowhere left to turn. She spared no details and when she finished, I asked her how she felt. She said it felt good to finally share.

A few days later, I asked about it again. I also reminded Mariah that I was gathering material for a book, and if she decided she didn’t want the story in the final manuscript, she could say so at any time. We continued to meet, and we grew closer over time, and Mariah never did ask me to take the story out.

Mariah’s story is difficult to encounter—as are the stories that so many other young people at Sullivan carry. I thought deeply about how, and whether, to include it. While I knew living with trauma was a central part of many of their lives, I never wanted to suggest that trauma defined their experience, and I wanted to avoid any chance of retriggering it. Refugee High wasn’t going to be a story about students’ endless suffering, but I also wasn’t interested in writing a Pollyannaish portrayal. I decided to include her story, and, with consent, many of the most challenging stories I heard because it gave me, and others, a truer picture of the complicated, and often painful, experience of adjusting to life in America.

Since finishing my reporting, I have kept in touch with Mariah. She just completed her first year of community college and she’s working, too. She doesn’t watch Riverdale anymore, but she has taken a liking to The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina. It’s now been almost four years since I first met Mariah, and I still find myself wondering what she’s reading, who she’s texting, and which dreams she continues to hold close. Refugee High is by no means the definitive refugee narrative, or even an authoritative one on Sullivan. It is just one version of this story, and I hope it creates avenues for more stories like these to be told. Who knows, maybe one day Mariah will write her own version. I would be first in line to buy it.

__________________________________

Adapted excerpt from Refugee High: Coming of Age in America. Used with the permission of the publisher, The New Press. Copyright © 2021 by Elly Fishman.

Elly Fishman

Elly Fishman worked as a senior editor and writer at Chicago magazine. Her features have won numerous awards including a City Regional Magazine Award for her article “Welcome to Refugee High,” her first report on the students and faculty at Chicago’s Roger C. Sullivan High School. Refugee High: Coming of Age in America (The New Press) is based on the article, and won the prestigious Studs and Ida Terkel Prize for a first book in the public interest. A Chicago native and graduate of the University of Chicago, Fishman currently lives in Milwaukee with her husband and their dog and teaches in the Journalism Department at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.