At six twenty p.m. Moscow time, Russian aircrafts attack Grozny. The bombs damage four power stations and a television tower.

The halls of the Vega are exceptionally quiet. Not even the TV in the common room is on. The potted palm curls up its leaves from the cold. Slowly the trail of muddy tracks that stretches from Natka’s office to the front doors of the Vega—which wobble on their hinges like they serve in a saloon—dries. Everyone but Sergey—who keeps reading books in his room on the second floor, playing songs every so often on his harmonica, playing himself in chess, packaging his jute bags for market—is sitting around the space heater, their eyes never wandering from its orange spirals.

“When we were living in Siberia,” Alex interrupts the silence, “there was this one cow named Apryelka.”

“Apryelka . . .” I repeat, because it strikes me as a nice name.

“Because she was born in April,” Alex explains. “That cow really made an impression on me. When she sensed we were about to sell her, she completely changed her behavior. She just wandered around mooing, with these tears pouring down her face like peas. Eventually my parents went to this struggling sovkhoz, where they bought Mayka. Mayka had been brought up under deep communism, getting her ears pierced, with this little number put in there. So then we went and took her home with us and started to just hang around a little where she was, started cleaning her, giving her different types of tasty treats, and it was like she could tell, I mean that we were really taking care of her, that we cared about her, and she became more similar to a dog or something. We never had to worry about her. We knew that if she went o somewhere she’d always come right back.”

“How’d you land in Siberia?” Waldek asks.

“My dad was in the military, they transferred him there. Meanwhile my grandpa got his electrician’s degree, and everybody told him not to enlist, because there had to be a man left in the village, but he wouldn’t hear of it. I’m not going to just sit around with the girls, he said. Although I think he regretted it later. In Smolensk, or not Smolensk, further west, as they were pulling up in their train there was this German flying his plane over them so low you could see his ugly mug and see that he was smiling, but our boys couldn’t do anything about it since all they had was just a couple of rifles. One day this guy Georgii comes up and says, Hey, you, look, there’s some lard there hanging o of that bush. Well, let’s eat it, hollers my grandpa, be- cause they hadn’t had anything to eat in two days or some such. He runs out and looks and what do you know, those smoked scraps were actually a piece of the nurse’s ass from when she’d stepped on a mine as she was trying to run off.”

“Where’d you learn to speak such great Polish?” I ask Alex.

“I learned it just like Natka did: from Poles.”

“But Natka grew up here, in the countryside, in Poland.”

“Alright, alright. I will confess. My mother taught me, her dad was a Pole; he lost his parents in Siberia when he was five, or maybe four, years old. All my pops could say in Polish was ‘hello,’ but whenever he got pissed off about something, he’d always swear in very old-fashioned Polish.”

“Why doesn’t Sergey speak Polish?”

“He does, he just doesn’t like to. He’s weird because when he was little he fell out of his stroller. First we were living in Georgia, in Tbilisi, because they’d sent our father there. Then we spent almost a year in Azerbaijan, in Baku and Nagorno-Karabakh, where there were riots.”

“You saw them?”

“I didn’t, because we were residing in a big apartment block by the army unit, but I saw the tanks heading in, and I’d wake up at night because of the shooting.”

“Were you scared?”

“Me? Nah. I actually wanted to go out there, but my mother would not permit me. All of us wanted to be in the army. Our father bought us a Makarov pistol that was just like the real thing, just blue so you could tell the difference, and you’d load these little caps into it. Plus we had shishigi.”

“What are shishigi?”

“GAZ-66 military four-by-fours. Sergey and I were al- ways hanging around the unit. There was this hole in the fence somewhere. You weren’t allowed to get into it, but we’d do it anyway, and one time I met Azer, this boy about my age. We started hanging around together, just hanging out and then whenever the unit alarm bell went o , we’d go up and hide in one of the army towers . . .”

Suddenly the beads at the entrance part, revealing Sergey’s head. Having overhead his brother’s story, he taps his forehead and recites something in Russian.

“What did he say?” I ask Alex, because although I supposedly studied Russian all through school I understand very little of it.

“It’s a poem by Fyodor Tyutchev,” answers Alex. “What does it say?”

“Let’s see . . . ‘Russia can’t be comprehended with the mind. Russia is unique. All you can do with Russia is believe.’”

Just then, as I’m about to mention the bombing of Grozny to the twins, Adelka leaps out of my lap and runs out into the hallway. The doors to the Vega open. At the clacking of Natka’s heels, the brothers get up, turn around and race up the stairs.

“What are they running away from her for?” I ask Waldek. “Haven’t they paid their rent?”

“What do you mean, college gal? You don’t know?”

“I guess not.”

“They’re both in love with her.”

“Well, what does she say about it?”

“Natka being Natka, she doesn’t say a thing. She’s still stuck on her old beau, Scurvy, who is alleged to have died in a car crash as he was making his way to Deutschland.”

–Translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft

__________________________________

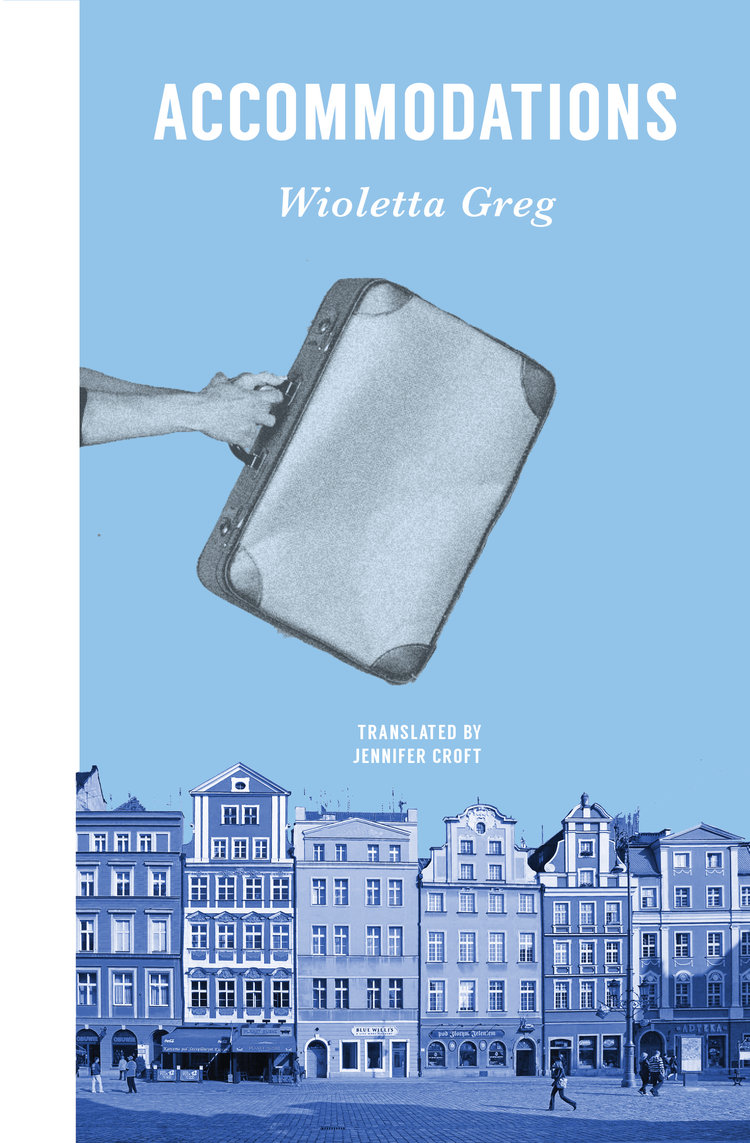

Excerpted from Accommodations by Wioletta Greg. Used with permission of Transit Books. Translation copyright © 2019 by Jennifer Croft.