Abel Ferrara Starred in His First Feature, a Mob-Backed Porno

The Acclaimed Director Looks Back on the Start of His Legendary Career

We broke up on December 7, 1974, Pearl Harbor Day. We had played out the string of this relationship. Nadia and I were living in an old house in Nyack on the Hudson River, a forty-minute drive north of Manhattan but as far away as the moon.

We were in that dark place for college sweethearts when college is over. I was spending days commuting into the city, trying to find a paying job in the film business, willing to do anything. I was in no-man’s-land, either make a living in the real world as a filmmaker or work the rest of my life driving a scrap metal truck for my father or a garbage truck for my uncle. I was doing it part-time, out of family responsibility and because I needed the cash. Everyone I knew was watching, seeing if I could make that leap from university hotshot to life as a working director.

Nadia had made up her mind about her future. She wanted out. She had been the star of my graduate film Could This Be Love, a twenty-six-minute color sync sound film which was to be our ticket to paradise. She was the cool blonde playing the lead. She wanted to be an actress, but she didn’t have the fire that was raging inside of me. We finished the film in the summer and now it was the dead of winter. I came home exhausted from work and she just laid it on me. She was in love with a friend of mine, a successful NYC photographer who she was modeling on and off for, with a big studio downtown and an apartment on Central Park South.

I felt good, thankful to have friends like him and a place to begin again, until the middle of the night when I woke up in tears, shattered by the heartbreak of losing my first true love.

“You want to leave right now?”

“Yes.”

“Tonight?”

“Yes, I want to be with him tonight.”

“It can’t wait till after Christmas? My mother and sisters already bought you a present.”

No, it couldn’t. It was her apartment, in theory, that we were sharing the rent on. So in the face of her honesty, in the early darkness of December, I put on the only suit I had, a blue velvet one I bought for someone’s wedding, and picked up my Goya guitar and the large 16mm film can that held my university thesis. We had spent a year of our lives on it, plus a few thousand dollars of my mother’s money and the blood and favors of everyone we knew. Could This Be Love, right. I got in my car feeling released, intoxicated, jet-propelled into my future and drove off deeper into the suburban heartland of Rockland County, Pearl River, to another big old white house like the one I had just left.

Dennis was an artist and classical piano player who was an actor in the film. It was his house, and when he saw me standing there he began laughing hysterically in that high-pitched voice of his. He knew the whole story without asking and led me to a monk-style room on the second floor with a desk and a bed and a window looking out into the backwoods.

I felt good, thankful to have friends like him and a place to begin again, until the middle of the night when I woke up in tears, shattered by the heartbreak of losing my first true love. We had had our ups and downs and mini-breakups over the past five years but she was everything a dude from Peekskill could imagine in a girlfriend. Tall, beautiful, from an aristocratic Russian family with European manners, a light-year from the blue-collar Southern Italian war zone I came from. We met as freshmen at Rockland Community College, which coming from Northern Westchester was like studying at the Sorbonne.

It was five in the afternoon, which is when their office opened, just as the rest of the building was getting ready to go home.

Now that life was over and I knew it, but to deal with it was a new lesson in extended pain. Dylan’s new album came out, Blood On the Tracks. Dennis had some nice speakers and a turntable and like every brokenhearted motherfucker I listened to that record a million times.

Matty Ianniello’s office was in Midtown Manhattan in the 50s off Sixth Avenue, on a block full of the highest rents per square foot in the world. In 1975 Matty the Horse, as he was called, ruled Midtown. The go-go club scene was in full swing, along with the X-rated theaters. That was the legitimate side. The high-end gambling parlors, the second-story shit, Wall Street swindling, phony credit cards, and any hustle you can think of were also his. Like Walken says in King of New York, “A nickel bag gets sold in the park, I want in.”

And that’s how it was, anything shady going down in Midtown, he was your partner. This was a golden age for these guys, ten years before Giuliani and any kind of real government crackdown, and a few years after Coppola’s Godfather.

Matty wasn’t your average wise guy, you didn’t get to where he got by just breaking heads, you needed the brains and the charisma to go with the willingness to adhere to the code. The real scary guys were those who came back from the war and hit the streets with all that good stuff they learned, how to use explosives and how to really handle weapons. Matty was a hero in World War II, served in the Pacific theater with the medals of bravery to show for it.

The introduction was from my father, who was a friend of his in another lifetime. Tired of watching me struggle and fail through a series of potential investors, my father figured it was time to introduce me to the people who could really help me. The slick lobby was guarded by uniformed doormen and the elevator took me to a long polished corridor leading to a big mahogany door. Inside was an office that appeared to be from another building, with some secondhand furniture in what might have been a waiting room and, behind a funky glass counter, a heavily made-up woman acting out the role of receptionist. It was five in the afternoon, which is when their office opened, just as the rest of the building was getting ready to go home.

She told me to go inside and wait in his office.

Nobody used his name.

His office was a big table with nothing on it, two chairs at either end and a forgotten filing cabinet in the corner. After a few minutes Matty walked in and sat across from me. He looked liked Luca Brasi from Coppola’s film and spoke so deep and gravelly that if you weren’t raised on it you wouldn’t understand one word. Years later in the same office he would hand me the FBI indictment against him, pages of transcribed wiretaps, asking me, “What did they say I did?” Reading what some middle American FBI guys thought they heard on that wire was hysterical, except that he went to jail for it.

But back then nobody was putting him away, nobody was even trying. He sat in that chair across from me without a worry in the world. He was a big dude, not fat but big. If it came to guns, fine, but he could handle himself without one. He was sharp, street-smart. I would come to learn he had a gift for sizing up a situation, making a plan, and acting on it in the same moment. He listened to my pitch, which was basically asking for money for my new film, and said come back in a week and he would let me know.

Being alone in NYC for the first time is exhilarating but diabolically lonely, the alone you feel surrounded by 10 million people, with no friends, no money, and a heart still in a thousand pieces.

It doesn’t take more than a few positive words when you are at this stage of asking for money. Even now I can turn “I will let you know” into accepting an Academy Award or two. Mark Twain said, “The worst things in my life never happened.” Well you can add the best things to that too. But in my business you’ll use anything for a bit of traction.

It was February in 1975 and NYC was cold and dangerous. My first apartment on 15th and Union Square was a studio in a classy old building with marble pillars, one small room with a bigger bathroom and strangely an even bigger closet. Union Square, which was to be my neighborhood for the next twenty-five years, was off limits after dark back then. It is the first main subway stop from Brooklyn and all the young thugs made it their own. Nighttime was Dobermans barking and occasional gunshots and I don’t think I ever went in there after the streetlights went on.

The city was going bankrupt, the cops were on strike, and a fire had wiped out telephone service in my part of the East Side. There were a couple of AT&T trucks filled with pay phones parked on Third Avenue, and that was it for communication out, communication in was zero. I remember trying the phone in my apartment incessantly for three weeks before one day I picked it up and heard a dial tone, a spiritual moment.

Being alone in NYC for the first time is exhilarating but diabolically lonely, the alone you feel surrounded by 10 million people, with no friends, no money, and a heart still in a thousand pieces. My longtime composer Joe Delia’s brother Frank shared the photo studio on Fifth and 13th with the guy who stole my girl, so what used to be a hangout was now enemy territory. Everyone I knew still lived upstate, so NYC at night was only mine. I learned where to walk and where not to, the best and cheapest pizza by the slice, the bars that would let you in to hear music without having to buy a drink.

I got some kind of flu and was laid up with nothing but tap water and change to call my mother from the phone truck, when I heard a knock at my door. It was my uncle Bobo, my father’s younger brother, my god-father and confidant throughout my childhood. He was a sweet and gentle soul and I loved and adored him.

How he found my place or got past the doorman was part of his mystique. He was doing business in town and wanted to make sure I was all right. I was recovered enough to go with him to Pete’s Tavern, a classic expensive restaurant down the block. He ordered all my favorite food and just smoked a cigarette as I ate everything that was put in front of me. He lived up in Bridgeport, Connecticut, another funky destination like Peekskill, part of my family’s diaspora from the Bronx.

He said, “Your father is not happy.” He didn’t say disappointed, but that’s what it really was. My father loved me, his only son, too much to say it, so he left it to his kid brother to tell me that broke and unemployed at twenty-four, with a useless degree and few prospects, wasn’t exactly the vision he had for me.

When I was in my final year of university I took the law boards, an entrance exam, more as a lark but also to stay close to a school’s free film equipment, my lifeline. I took a Black Beauty and miraculously did well. I envisioned going to law school and emerging three years later with a degree and a few more films made, a superhero independent filmmaker entertainment lawyer. I was brought back to earth by my friend’s brother, a lawyer. When I said I was applying he said, “I thought you were going to be a filmmaker.”

I said I would do both and he laughed at me, saying, “The first two years of law school I didn’t have time to read the newspaper.” I took his word for it.

From the time I started making 8mm films as a sixteen-year-old she was there, my go-to financier, taking money out of my father’s pants pocket he didn’t even know he had while he was sleeping.

But now my uncle was bringing it up again. He put an offer on the table. There was a law school in Connecticut near him and he knew people there that could get me in. He would pay for my education, get me my own place near the school, and give me money to live on. How many people have uncles like that? I said no, I am making a film, I have a plan. He said, “It would make your mother happy.” That was a low blow, but still I refused.

My mother was not Italian. She was a beautiful Irish woman, blue-eyed, blond-haired, every bit the Marilyn Monroe to my father’s Joe DiMaggio, which was the template for these interracial marriages. My aunts and uncles all went the safe route and married Italians or Jews. My mother was also born in the South Bronx but she came from abject poverty, not a working-class immigrant family like my father’s. She lost both her parents when she was fourteen and had to raise her younger sister and three younger brothers, with little help from her two older brothers, who were still in their teens and well on their way to being Irish drunks. Somehow she kept the family together.

As a child of welfare, the luxuries of a bourgeois housewife meant zero to her. She could appreciate the comfort zone but didn’t trust it or need it. When you grow up with Christmas being a grapefruit, and an orange for your sister, it makes you grateful for what’s real.

For her, as long as I wasn’t dead or in jail she was fine. Maybe because of the star dreams of her older brother Kenneth, a failed vaudeville song-and-dance man and my only relative that was remotely associated with show business, she got what I was shooting for. From the time I started making 8mm films as a sixteen-year-old she was there, my go-to financier, taking money out of my father’s pants pocket he didn’t even know he had while he was sleeping. Dorothy O’Brien was cool like that.

I went back to Matty’s office and waited at the same empty desk. I could hear people talking in the other room, his business partners, guys I would get to know later, Benny Cohen, Robbie Margulies, slick dudes, perfectly manicured fingernails and razor haircuts. My father always preached to me that you can’t make money with Italians, you had to stick with Jews, Italians were too resentful and jealous to get anywhere with. Then he would rattle off the names of some serious Italian gangsters, followed by a Jewish guy you never heard of.

When they got to Matty it was Benny and Robbie, and now here they were. Robbie I especially grew to like. His brother owned a famous uptown steakhouse, and who knows everything that Robbie was into. He was making oil deals with the Russians and was involved in casinos in Las Vegas and Atlantic City. He was one of the few people in the world able to count cards at the blackjack table, which would have gotten him banned from his own casinos. He was the first guy I ever saw wearing gold bling around his neck, along with the rings and Rolexes they all had.

This was a serious favor to extend to the son of an old friend, to take me from nowhere and propel me to the middle of that whole game.

Matty came in the room, sat down, and laid out his proposal. “You know Jerry Weintraub?” Jerry Weintraub was Frank Sinatra’s manager, as well as a major Hollywood producer making big-budget movies. “Jerry will fly you out to California, he will give you $500 a week and you follow him around.”

“What do you mean follow him around?”

“You know, carry his bag, do what he needs you to do.”

This was a serious favor to extend to the son of an old friend, to take me from nowhere and propel me to the middle of that whole game. Except I wanted to make a movie, not follow some guy around, no matter who he was. I thanked him for the offer but told him again I was trying to raise $25,000 to make the film. In a prescient moment, which is what separated him from most of the others, he said, “Why do you want to ruin your father?” Then he stood up, told me to wait there, and left. Twenty-five minutes later in walked Franky C.

Franky was what they referred to as a smart guy, and for the next thirty-five years he would be my sometime manager, producer, and actor. He was someone I could always count on when I needed it most.

The breakdown is this: A smart guy is a guy who can make money. A tough guy is a leg-breaker and maybe a killer. A wise guy is a killer, a made man, and you had to be 100 percent Italian to be in that club. Gerard Damiano was a smart guy, a hairdresser from the Bronx who directed Deep Throat and the follow-up, Devil in Miss Jones, which were killing it at the box office, high up on Variety’s Top 50 list of the highestgrossing films.

He introduced me to his producer Tommy from Miami, who was definitely a tough guy and was the one who ended up making all the money. When I told him I needed some help to get in the business he turned cold and said, “You’re not thinking about ripping us off, right?”

“No, I just want to make a movie.”

A meeting was set for ten o’clock the following night, which was mid-morning to these guys. Lino’s is a restaurant on 35th Street buried deep in the Garment District. The place was empty except for the maître d’ who, when I told him who I was meeting, sat me in a side booth. Tommy shows up looking slick with the go-to Julius Caesar haircut, his wide collar open over wider lapels, with a Kim Novak look-alike walking alongside. 1975 was the real fashion year for ridiculous-looking shit but at least she could make it work. I was too wound up to eat and said I would order later. He just had a drink and waited while they brought her out a dish of veal parmigiana with a side of spaghetti. She starts eating like it’s the last meal of her life.

After an awkward ten minutes he says, “Is your guy coming or not?”

Just then a dude who was sitting at the bar in the corner comes up to us. He is dressed in a dark conservative suit with a dark shirt, no tie, pretty much like I was. With a Hester Street accent, as opposed to the Broome Street one that Matty had, he says, “My friend is on his way.”

He goes back to the bar and we wait for what seems like an eternity, then Franky C shows up. He is also dressed in the fashion, only he’s wearing a tie. Franky believed in ties. I once saw him buy a thousand dollars’ worth of them while waiting for a plane. “It’s the topper,” he used to say. Franky is of medium height and back then he weighed close to four hundred pounds. He sits down next to Tommy and the guy at the bar, whose name is Z, comes over uninvited and sits next to me. There’s some small talk and then we get down to business.

In the end it was my father who put up the 25k.

Tommy starts explaining how it works, what us creative types have to look forward to for the rest of our lives. We come in with the ideas, the energy, do most of the work and for their investment the financiers figure whatever money gets made is theirs. We keep the glory. These were gangsters, so they weren’t obliged to couch this any way but direct. Pointing his finger at me, Tommy laid out the next fifty years of my movie business existence. “Who gets ripped off? It’s guys like him who get ripped off.”

It was the last sentence that got Z’s attention. He looked right at Tommy. “He’s from our office. Nobody rips him off.”

Z was the real deal, intense, with a thin wiry body and narrow eyes. Downtown he was known as the Chinaman. Focusing on him for the first time, Tommy got the picture, and he didn’t like it. He was stuck between Kim Novak and a wall on one side and a four-hundred-pound dude on the other. Across the table was me, a long-haired, crazed maybe-director, and Z, who if Tommy didn’t know before he did now. But Tommy stays cool, turns, puts his hand in front of his mouth and whispers in Franky’s ear, “So who are you with?”

“The fat guy,” Franky says, the term they used for Matty. Tommy is incredulous but relieved because he works for him too. “You’re with him and you’re asking me for money? Why don’t you give him the money yourselves?” Franky says, “I’d rather buy him a house.”

In the end it was my father who put up the 25k. The deal he made with Matty was that he would front the money and Matty would watch over the production and keep an eye on me and make sure no one bothered us. So now Franky C, his pal Cha Cha, and the rest of that gang were my producers.

If we were only smart enough to film their real lives we would have made a great movie.

Nicky St. John, my screenwriter and filmmaking partner, had just come back from Germany with a master’s in philosophy from the University of Würzburg. We were ready to start our careers, and now we belonged to something. We had a start date to make a 35mm film with a clear distribution plan. NYC was no longer a fortress of closed doors. We were hooked up.

Mulberry Street between Hester and Canal was our new stomping ground and shooting location. No more steady diets of Stromboli pizza with that syrupy fake cola, although if it wasn’t for the generosity of those young Sicilians who ran the pizzeria on 13th and University we would have already starved to death. When you’re sitting at Umberto’s and Matty comes in and tells the waiter he’s got your check, New York becomes what everyone dreams it can be.

Our production office was uptown, Mambo Hy Talent Agency between 53rd and 54th, a five-room apartment overlooking Broadway. You could look across Seventh Avenue and see the Stage Deli on one corner and the Carnegie on the other. This was no downtown scene, this was Broadway and all the show people and ballplayers and serious mob guys were right there, and Franky C knew them all, from Jackie Wilson to Clay Cole to Tiny Tim.

Mambo Hy was the agency for the girls who danced in the topless clubs. They had made-up names like Smokey and Lola and Gemini and were from every walk of life. Some were students working their way through school, digging the independence from their families that that kind of money gave them. Go-go clubs ruled back then, they were like theater, and the audience wasn’t just guys in trench coats. Limousines full of fashionable people would pull up to clubs called The Carousel, The Playpen, and The Pussycat Lounge.

The girls also worked the seedy bars filled with seedy people in places like Lake Ronkonkoma or out in Jersey somewhere, and because they all belonged to Matty there was some semblance of order. He was a security blanket that stretched far into the boroughs.

When it came time to cast the film we did not want professional porno actors or actresses. We had convinced ourselves we were making a real film so we were looking for real people. We must have been pretty persuasive about the validity of our movie because we attracted three of Mambo Hy’s best dancers for our leads.

Chantal may or may not have come from France but she was a killer, long black curly hair, an intriguing damaged face. Ava was a big athletic blonde who could have had a chance in Hollywood. Joy was Black, with a strong gay side like a lot of the dancers. She was over-the-top beautiful, funny, outrageous, somehow holding on to her innocence. I’ve never seen anyone with her color skin. It was amber and glowed in the right light from the right camera angle.

We made the day and everybody was happy, only I had a mother and now three daughters and I have to live with that.

They say you have to love them to direct them, so I had no excuses for this film. Their backstories, which you got in dribs and drabs, were astounding and left them streetwise and tough. If we were only smart enough to film their real lives we would have made a great movie.

The script bounced us all around location-wise so we figured we would start in Frank Delia’s photo studio for the exposition stuff and then move to the apartment Cha Cha had above his cafe on Mulberry Street, another “safe” environment. We could delude ourselves that we were making Salò or Last Tango or a Fassbinder movie, but this was a Triple X movie, real sex, cum shots, and people were getting busted for that as well as making fortunes. Who cares? We were making our first 35mm feature and I wasn’t even twenty-five.

Shooting actual sex is not so simple. When approaching a film you have to invent a method of shooting to capture the action inherent to that project. You discover it shot to shot. There is no other way.

In the middle of figuring it all out the one actual porno actor we cast couldn’t get it up. That’s a disaster. I am giving this guy 300 bucks, a small fortune, to fuck what is essentially our girlfriends, and he can’t do it. It’s an insult.

Cha Cha and Franky C are sitting downstairs in beach chairs playing producers, and they’re not happy to hear that we’re about to blow a day’s shoot. Between me freaking out and the actor realizing exactly who he’s pissing off, the dude makes the brilliant move of slipping out the bathroom window, down the back fire escape, and off somewhere into the Lower East Side.

I grew up choosing up sides or playing rock, paper, scissors, all games with your fingers. Drawing straws was something out of a World War II movie but that’s how we did it. It was me, Frank Delia, and a couple of the crew guys, and I got the short one.

The scene was the story of Job that Nicky St. John lifted from the Bible, how the two daughters had to do their father to procreate the race. So they put some talcum powder on my head and I acted like I was sleeping while Chantal and Ava worked out on me.

We made the day and everybody was happy, only I had a mother and now three daughters and I have to live with that. My mother raised me to respect women and respect myself, and in this film we crossed that line. To continue to make hard-core movies was not us, it was against our nature, so we stopped after one.

__________________________________

From Scene by Abel Ferrara. Used with the permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2025 by Abel Ferrara.

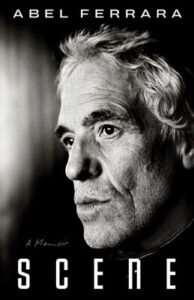

Abel Ferrara

Abel Ferrara is a critically acclaimed film director. Some of his cult classic works include Bad Lieutenant, King of New York, and Dangerous Game. He lives in Rome.