It is told this way:

Not so long ago, on a winter’s afternoon in a small town in Mexico, a volcano was born. As the youngest volcano in the world, it is the only one with an ample record of the years following its birth beside the home of Demetrio and Bernarda.

Demetrio, who owned the tract of land where the volcano was born, was plowing the soil with two oxen one afternoon when he heard a rumbling underground. He thought it was an earthquake like the one that had shaken the town days earlier, raising clouds of dust and covering his roof boards with dirt. The rumbling was followed by a slight tremor that raised only a thin puff of dust, like the ones that formed and vanished as the oxen walked. Other weak tremors, sensed by a few of the animals, followed one another like a line vanishing into the horizon. Demetrio was plowing his land and thinking about how he would need to sweep the dirt from his roof boards again when suddenly he heard an explosion like a sharp crack underground. His oxen spooked and a wisp of smoke began to rise from the earth.

Demetrio hurried back to the house to tell Bernarda what had just happened; she left in search of the priest to tell him what was happening on their land. In those days, the priest was supervising the construction of a church that would bring the two neighboring towns together. The priest was not at the unfinished church, but one of the builders told Bernarda to look for him at his troje. Demetrio paced, not knowing what to do, as the sunset and a wisp of smoke continued to rise from behind his home. The smoke seemed endless, like how night follows day. That wisp of smoke reminded him of the tornado that had once formed on the other side of the milpa when he was a boy; it had come upon him at a sprint as the dogs barked, and if he remembers anything, it is that feeling of terror and the roar of the raging air when it twists itself into a tornado.

Bernarda returned to their land with the priest just before night fell, and the three of them examined by candlelight the place where the wisp of smoke had risen but no longer rose, as if it were hiding underground. There was nothing but a long, long crack in the ground, like the ones that open during a drought before the first rains of spring. There was no smoke, but the earth was as hot as a comal over a flame. The priest could not fathom why the earth was so hot, how its temperature could have changed, or why it smelled so strange. When he smelled the odor coming from it, so fetid it was as if the earth were dying inside, he closed his eyes and began to pray. Bernarda followed suit, while Demetrio, his mind completely blank, simply closed his eyes.

Demetrio couldn’t sleep that night. What would happen if the earth thundered again? What if the smoke was a terrible omen? What if God was punishing them? And what would happen if the wisp of smoke became a tornado? A tornado incubating down there that—as soon as it touched the earth, like a colt fresh from the mare—would take his crop and the milpa with it. What would happen if that wisp of hot smoke with its violent smell killed his oxen and goats? His wife slept like a rock despite the day’s strangeness. Demetrio drank one cup of water after another that night, as if unsure what to do with his wakeful body. He finally managed to doze off, and the little sleep he did get mingled with sounds that came either from his dreams or from the depths of the earth, he did not know which. Just before the sky began to lighten, at that hour when the sun’s first rays faintly announce their presence and the horizon seems to have caught fire, he opened the door to his home and saw a small black hill that had not been on his land a few hours before. But what was a small black hill doing on his doorstep? How had it gotten there? No one in town could have possibly done them the wrong of putting a small black hill on their land. Demetrio walked toward the newborn volcano, which at that hour of the morning looked darker than the night, and the sun’s first rays seemed to want to hold it out to him with open hands. There it was: a black hill the size of a parish church. With a strange hole at its peak.

The hole at the peak of the newborn volcano changed shape right in front of him, as if it were a living thing. Demetrio stared at it. It looked like one of the horseshoes they have so many of on the haciendas. It was changing shape, but he thought it looked like the muzzle of a newborn animal that had come with its unknown language from the depths of the earth. When day broke, the newborn volcano grew a bit more, and when the sun came out from between the mountains, Demetrio could no longer see his neighbor’s milpa, and a vast guilt swelled in him.

None of the houses or trojes in town had more than two rooms; most houses had only one and were built of adobe slabs that held the heat in during the winter and stayed cool in the summer. Some had wooden walls that let in the sun’s rays in the morning to form strips of light and shadow on the dirt floors; others had their kitchens outside in a little hutch; some had no roof; several had chicken coops and pigs and other animals in pens; and there were a few pine-beamed trojes that had been passed down from generation to generation. Some of those had been around for two or three centuries, which made the town look like something from another time. The priest’s troje and his tract of land had been gifts from one of the landowners in the next town over, in exchange for officiating at the first communion of his twin daughters on his avocado plantation.

The church—a pile of stones, dirt, lime, concrete, and three pillars that were about as useful as three legs on a table—had a courtyard paved with concrete where a market was set up every weekend. There was no high school in town, or in the next town over, and no one knew or wanted to know what high school was for, but there were three pulquerías where you could buy aguardiente, rum, and tequila. One of them was famous for the spicy mix of roasted peanuts, fava beans, and corn they made fresh every day. There were no hospitals around, and the nearest clinic—a dilapidated structure with blown-out fluorescent bulbs—was miles away, but there was an older woman with heavy breasts who was no more than four and a half feet tall and wore her hair in the same braids crossed over her back as she had in her adolescence. She tended to the ill and the lovesick with her herbs and her mushrooms and the fire circles she made in little tins to perform her rituals—she always made the same circles on her land, creating different geometries inside them that she translated according to her visitor’s affliction, as if the affliction itself were speaking to her, dictating the patterns. If she lit one of her fire circles at night, by morning the rumors were already swirling about what deal she’d made with the devil. It was also known that she was the only person in any of the surrounding towns who could take unwanted children from the sight of God; she would make an elixir in those same empty tins she used for her fire circles and she would give it to pregnant woman who did not want to give birth. They came to see her from far away; she was a woman of few words with no husband or children. Not much was known about her past, but everyone knew that when she was a little girl, her father had been gunned down for casting spells and that she had watched him die.

The townspeople gathered for Mass every Sunday in the courtyard of the unfinished church. There was a canopy held up by five log posts, the tallest one at the center, and from it hung strings of white paper flowers that the wife of the avocado plantation owner had commissioned for the first communion of their twin daughters as a gift to the town, since the party had been on their hacienda. This was the only elegant detail in the entire town, like a delicate brooch pinned on a coarse garment. The nearest cemetery, which was next to a forest, was shared with the neighboring town. One night each year, on the Day of the Dead, most of the townspeople walked by candlelight along the edge of the forest that divided the two towns, sipping corn atole that they heated in great copper pots to ward off the cold. Families shared food to pass the night, and Demetrio and Bernarda usually joined one of them. Their children lived four hours away, except the eldest, who had settled in the United States without papers after crossing the desert on foot with other men from their town. Demetrio and Bernarda often spent the Day of the Dead with a family whose son had also crossed the desert on foot; they would bring offerings for their youngest daughter, who had died in a tragic accident caused by the mud that formed along the banks of the river during the summer rains.

Demetrio and Bernarda’s tract of land, like those of almost everyone in town, was vast. Each house was a long walk from the next, except the small ones built on the town’s lone avenue—which, scrawny, dusty, and neglected, was like a stray dog everyone knew. The hectares between Demetrio’s house and his neighbor’s seemed to have shrunk with the birth of the volcano, which grew and grew, slowly blocking out the horizon. Its stench was growing stronger and more unpleasant, like a dead animal drawing flies, but it was also unlike the sweet odor given off by animals that die under the sun’s rays. Demetrio thought he might be able to pour lime into the mouth of the newborn volcano to cover the stench, at least, to overpower it with the help of his oxen and a few men; he was thinking that there was no reason for the earth to be so violent, being made by the hands of God, and that maybe he could destroy the newborn volcano, when it grew a bit more right in front of him, right under his nose.

That was the night of the exodus. A landowner who had contracted an agricultural engineer to plan his vegetable garden came over from the neighboring town, which was how the soldiers and the two geologists arrived. That was the night of the exodus, and when Demetrio and Bernarda looked back they saw the first spurt of lava set their home ablaze. In the distance, they could see how the burning rock flowed slowly from the peak, how it illuminated the neighbors’ milpas in its descent, how in its slow descent it set fire to all it touched. The roofing caught right away, the trojes swelled with flames. How could the land be so violent? The thick lava—black and orange, such serene colors, so harmonious—destroyed everything in its path with its blaze; Demetrio thought he saw the cemetery that held the body of the little girl they would visit on the Day of the Dead catch fire, and after that he decided not to look back again.

Five nights and six days after the exodus, the newborn volcano had grown to three times its original size, bigger than any cathedral anywhere in the faith, and the residents of the two neighboring towns settled in a campsite on land the soldiers designated while the government decided where to relocate them. They numbered 2,839 and one baby, who, with Bernarda’s help, had been born before dawn on the first day of the exodus. At the end of those nights and days, in the distance, they could see the volcano’s full shape and one church pillar, the only thing its birth had left intact.

The priest recited prayers with small groups of townspeople. He spoke to them of the miracle of God, of Jesus, who walks beside them, of the Holy Ghost. Nonetheless, the first thing the volcano had destroyed when it was born—aside from Demetrio and Bernarda’s land, which had happened almost by chance, because it could have been born in any other town, anywhere in the world, or, for that matter, in any other age, but the volcano seemed to have made a decision, as it if had had an agenda or, rather, an obsession— the first thing the volcano had destroyed was the faith of many, and many poured their faith into work or the money that came with the tourists who flocked to the area.

It is also told this way:

The rumor spread quickly that the devil was getting ready to emerge through the crack in the earth that had just opened on our land. Before it came, I didn’t understand that a volcano could show up on your doorstep the way drunks sometimes do in the morning hours. Demetrio went off with the other men who were milling around with their eyes on the black hill that had burst through the ground, they even tasted the earth from that ridge, with its smell like the dead. There were a few quakes before it began to peek through, but we had grown accustomed to them because they were soft, like two people telling secrets so no one else can hear. Afterward, we cleaned our rooftops with brooms, but those quakes were just the earth sneezing, we never imagined that a dead hill would push its way through the crack. I barely felt the last one, the one that birthed the volcano. I thought: Bernarda, it’s an earthquake. I didn’t think: It’s an earthquake that will bring with it a hill that smells like the dead. But it did: it wasn’t just a little quake, it brought the volcano we thought was a dead hill with a hole at the top, the volcano we believed was there because the devil wanted to punish us all. But nothing came out of that soft spot on its newborn skull, all it did was move. I thought: Nothing’s going to come out of that hole, that hill is probably just useless. Sometimes useless children are born into hardworking families, and maybe that ridge with its smell like the dead is useless like them, not even good for burning trash, out there among the others that are good for raising crops.

There was Demetrio with the other men, staring at it. We already knew we had to leave, because a gentleman told the soldiers that the thing on our doorstep was a volcano, that it wasn’t the devil. I went into our home and gathered our packs and I waited for Demetrio to tell me we were leaving, because I don’t give the orders around here. And he said to me: Bernarda, let’s go. So we went. We left the ridge and its smell of death behind on our land. The smell was everywhere and it frightened us all.

Demetrio carried the packs and I brought the goats and the oxen. I couldn’t carry the packs because all the little ones I’ve brought to the town had ruined my back. We gathered in the church courtyard, the Father spoke to us of Exodus from the Bible, he told us that God our Lord had a new place in store for us and we set off walking with our packs, trunks, and plow teams, with our mules, goats, hens, and pigs, with our food gourds, our crates, pots, and chairs, and even with our decorations. The newly born volcano gave off its first lava that night. From the camp we could see its blaze and red glow. Demetrio was frightened, I know the face of stone he makes when fear is trapped inside him, but I wasn’t frightened, because it looked pretty from far away and because I thought: Bernarda, this is God’s will. Someone said to me that the earth had felt smothered and just needed a place to breathe. I thought: This is how a woman breathes when she delivers. I thought: This is how we breathe after giving birth, and the little ones look just as yellow and sick when they’re born as the newly born volcano looks ugly and sick with its yellow glow. The land gives birth just like we give birth. And that was when I saw how the volcano was lighting up the night with its glow and the fires coming out of it, and I understood that everything was fine despite the pain because that is how it is to give birth. I saw the blaze coming out of the volcano and the light bursting out of it and they were beautiful in the dark of the night. And just like those beautiful bursts can be dangerous, danger can come from the children we birth.

The Father had asked us to bring the saints and we carried them among many of us. The only one who carried a skull adorned like Santa Muerte was the curandera. I thought: That’s her way, if someone says light, she says darkness, because darkness is her nature. I am a midwife, I brought mine and others’ into this world, and everyone knows she has ways to make sure little ones are not born. She was the only one who walked the exodus alone, without a pack, clutching that skull adorned like a saint, with its black eyes. She was also the only one who didn’t talk with the others, she marched along as silent as death. They say she stopped speaking after her father was killed in front of her.

Some of the animals died from the smoke that came from the volcano’s muzzle. A person died from the smoke too. His family carried his body to the camp. As the earth thundered from below, the way boiling oil thunders at drops of water, as we listened to the hot earth thundering on our exodus, a rumor began to spread that the curandera had made a deal with the devil, but I thought: Bernarda, her fires in tins couldn’t cause a head cold, much less split the earth in two. But the curandera almost never speaks, she just makes her shapes with fire, and I think this is why people are more frightened of her than they are of the volcano that drove us from our homes. The land can be dangerous. She looks gentle, but she can be cruel.

Darkness has its fortunes, so the volcano that sent us on our exodus carried with it more coins than we’d ever gathered between the two towns. We were poor, but the volcano put food in our mouths. It found its way into our hearts, even, with its smoke and its glow and the way it made the night beautiful. That was why I wasn’t afraid to look at it during our exodus, but Demetrio never turned around. We were frightened when the newly born volcano appeared near our milpa, right on our doorstep, because it appeared just like that and drove us all from our town. But it brought coins to us all, especially to the curandera, who got more than anyone because people said that her circles of fire had drawn fire from the earth. They said: That woman can do anything. And she was the one who became famous, they came to see her the way they came to see the volcano. More fame for the curandera than for the dangerous land.

Demetrio was invited to this, that, and the other university on the other side, he tried to sell the volcano to whatever gringo would listen, because it had been born on our doorstep, but Demetrio couldn’t sell water in a drought. And then he came back and went around with the tourists who spoke in different languages, because he’d learned a few words on the other side, and he would say, “Sank iu” and “Hau dew iu dew,” just like he’d been born there on the other side, and no one understood a word he said, but they were polite, you know, and they smiled because they were impressed by what was in front of them, not skinny Demetrio but instead the newly born volcano, the one that destroyed everything.

I made a journey to speak on the telephone with my boy who lives on the other side, and my grandson asked me if volcanos talked in stone. And I thought: Yes, the volcano is telling us something with its rocks. I also thought: We understand what the earth tells us when it speaks in water, in soil and seed, in trees and chayotes and squash and avocados, but not when it speaks in burning stone. One day I got close to the volcano’s rumble, which Demetrio said was like the rumble of the tornado that had held him captive as a child, and he said that the earth and the wind are equals in their rage. Demetrio never stopped talking about how the tract was ours, and more words came out of him than burning stone from the volcano, because he might be skinny but he’s a bottomless pit. And so money came in every day, with Demetrio telling what happened on our land with all the words that came out of him, and every day was like Christmas for us.

The tourists arrived and offered us tips for bringing them to the volcano and helping them with their photographs and videos, because some of them arrived with cameras to show the volcano in the parts of the world they were from. They left clothing, objects, they came from all over to see it. They wrote news reports about it in different languages, made videos, took photographs, they did all kinds of things to the volcano, and for all that they left money, so much that I thought: The volcano also spits out coins. I also thought: They are taking money from the rageful land. Many people questioned the will of God our Lord, but I thought: God exists, and just as He creates He also destroys, just like the volcano that destroyed everything we had. It took our land from us and our town, and in return it gave us so many coins we could have made another hill next to the volcano of nothing but coins. There were those who wished another two or three volcanos would be born so they could gather even more coins, but who cares more about coins than about the land?

__________________________________

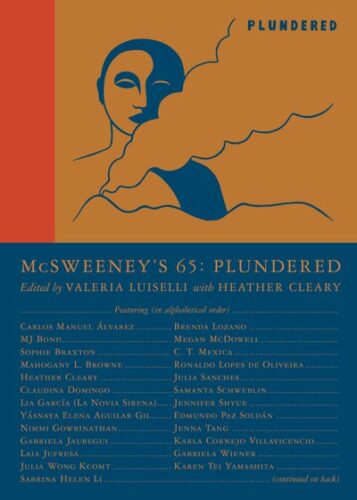

Excerpted from McSweeny’s 65: Plundered, edited by Heather Cleary and Valeria Luiselli.