A View with a Room: How Poetry Can Save the Human Brain

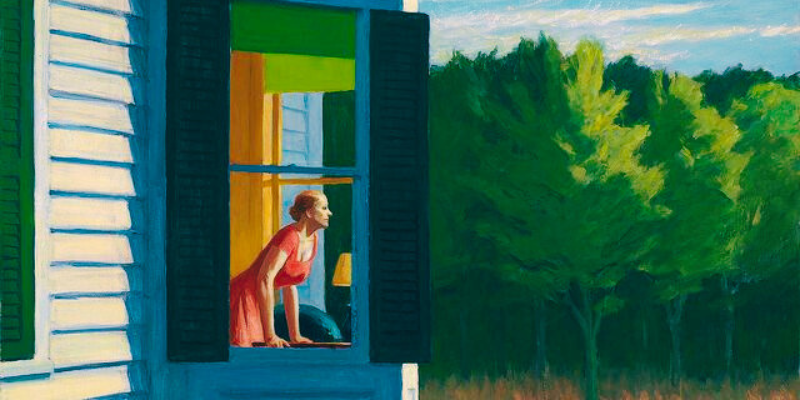

Kate Colby on Finding Inspiration in Edward Hopper’s “Cape Cod Morning”

I can’t write. It’s been over a year since I wrote a poem or anything at all, really, and this is not normal for me; I am always always writing. I’ve written my way through the hardest parts of my adult life. In fact, worry and lack of time have historically induced me to write more, as though I’ve used the conditions for not writing as a useful writing constraint.

My first baby was a terrible sleeper and I wrote furiously while sitting outside his bedroom door. I wrote a whole book at stop lights while commuting to a teaching job twice weekly. During a period of particular turmoil a few years later I exsanguinated poems, most of which will never see the light of day, but still. I thought the sound of small socked feet kicking the crib bars was a forbidding condition for writing. I thought toddlers would flood my brain with their tedium and unrelenting ooze of fluids. The string of puppies, too, with their chewing and barking and shoe-stealing should have taken a toll on my thinking and ability to commit it to the page, but none of these prevented me from churning out poems and essays at a clip that barely made sense, and it saved me.

The platforms are still there but the frenzy is over. There is nothing remotely motivating to be found in those vacant and echo-y rooms.

Here are some very good reasons for not writing: an excruciating back problem that flares up frequently and prevents me from touching a keyboard, two teens with challenges and emotional needs, two siblings who are killing my parents, and two aging parents who are winding down operations regardless of the siblings. There’s an unspeakable political situation, work work work, the constant need of wiping of things, the siren call of a gazillion gaudy facets of the internet. Menopause, tendinitis, overextended friends I bottomlessly need but hardly see, neverending worries about my kids’ prospects in a dehumanizing world of humans busily dehumanizing one another. What if they have children? I can’t abide the thought of them shouldering these worries but probably tenfold.

Those are not the reasons. I think back to around 2017 when writers’ attention was clumped in the same few places and in real time. It was an awful frenzy. Everyone climbing on top of each other’s heads trying to get to the top, the top consisting of the rare viral success that came with a pile-on of viral criticism. Those lucky/sitting ducks were at the center of a manifold creative pressure, like the core of a planet pulled spherical by gravity.

I did not long for that fame, I really did not, but I miss the clamor, all the anxious eyeballs pushing me to work under collective scrutiny. Now we’ve all scattered to the winds, abandoned the platforms. The platforms are still there but the frenzy is over. There is nothing remotely motivating to be found in those vacant and echo-y rooms.

I don’t know but I wonder if even the poets for a large part have stopped reading poetry. I know I haven’t been lately, though I still have a deep faith that attention to the nuts and bolts of language, the modeling clay of human reality, is critical to keeping us human by which I mean conscious of our consciousness and how it works and tricks us.

With AI leading humanity toward the exit by our elbows, the internet’s bottomlessly banal offerings ironing our collective and respective experiences into a rigid scroll, keeping a laser-focus on our language and its built-in and combinatoric prevarications is of the essence. Art concerns particularities of human existence framed by the big picture, but the picture has swallowed the frame.

The stop light made me think about the power of noticing and that one needs to notice in order to write and want to read poems.

I have all but stopped noticing, which I just noticed in a rare glimmer of lucidity. I drive around Providence in a fog. Yesterday, though, it occurred to me that the true red of a stoplight is deep and beautiful while the go green is ugly and insipid. It made me think of an article I read about the Disney Corporation’s proprietary paint color with which it paints dumpsters and drainpipes and other unsightly infrastructural elements in its theme parks so that they don’t detract from the magic for visitors. The paint color is named “Go Away Green.” It is neither light nor dark nor bright nor dull. It is merely ambient, disappearing whatever it adheres to.

The stop light made me think about the power of noticing and that one needs to notice in order to write and want to read poems. I made a vow to crank up my old noticing mechanisms, which would require divesting from media and its totalizing constructs. I would have to divest from other parents with their global anxieties. I would have to divest from the future, though not futurity. It’s that last thing I want back. Go away politicians, go away college admissions, go away desertification.

It’s not happening.

Before I stopped writing, I had been writing about failing at writing about Edward Hopper’s Cape Cod Morning for a good five years, and since I started trying to write about the painting while art was still coughing up a few sparks, I am interested in the difference between what I couldn’t say about it then and what I can’t say about it now. I know there is a difference because the image still reminds me of me, but I do not remind myself of myself as I was five-plus years ago. I can try to describe what I wanted to say about it then, though, because I drew a grid on the picture with a ballpoint pen that remains as a record.

The painting is of a woman, neither young nor old, in a bay window. We see her from the side, leaning on a table and looking intently through the glass, as though guiding a ship through an ice field. The outer edge of the protruding window exactly bisects the painting, so that the human elements—the house and the window and the woman they contain—occupy its left half and the natural elements the right. The left is crisply defined by light and shade and nested architectural frames. The right is soft and layered in a zero-point-perspective trifle—one third sky, one third trees, one third half-and-half: dark forest understory foregrounded by golden sunlit grass.

It is summer and the bright white house is sharply shadowed in accordance with the clear morning light and Hopper’s glaring American chiaroscuro, dark lines beneath the lips of the overlapping clapboards. The facet of the jutting window that faces us is shaded while the woman within its little room is well-lit, indicating that the sun is coming up in front of her, which in turn indicates that she is looking to the east, toward the ocean. The golden grass stretching out before her and the house would seem to be a meadow above the sea.

The dark woods not far off to her left, at the end of the viewer’s view, are not typically seen marching up to the sea in New England like that—we usually get some scrappy stuff and twisted, salt-stunted pines, not these fine upstanding trees—but the painting’s title insists on sea and that she is looking out at it, seeming by her stance to be riveted. Something terrible has happened or is about to, or else she is just noticing things intently.

With a ruler, I drew a grid of nine squares on the image, which I had ripped out from a magazine. I was trying to understand the composition of the painting, which, I was both gratified and let down to realize, strictly adheres to the rule of thirds. Per this rule, you don’t center the important elements of your image—especially not the horizon—but stick them a third of the way out toward the edge, ideally on the “power points” where four gridlines intersect.

It is double vision that I and we, the poets, need to employ like mad to keep us distinguishable from the machines.

I drew the grid in order to locate the power points and, wouldn’t you know, the lower left one falls smack in the center of the woman’s body. Then I drew a grid of nine squares in the center square of my grid and discovered that her face is centered in the lower left square of that grid. I did not draw a grid on that square, but I can see that her face is centered on the upper right power point of that one.

If I could re-center and keep ratcheting in on the image, like Harrison Ford in a forensic moment of Blade Runner (presaging the manner in which we now pinch and zoom in on digital images, which I increasingly have to resist doing to images in print), I don’t think but sense that it would just keep receding by halves and thirds in turn till I reached the elemental point of the painting, which may or may not be—in this case and also generally—the same as the vanishing point, which in this case, to my eye, is right at the end of the woman’s nose. The whole image is a set of geometric elements receding precisely, which either or both ruins or/and enhances a little of the painting’s magic for me. Go away ruler. Go away instinct.

She is looking about her looking.

Go away, Harrison Ford! There’s only madness at the bottom of that picture.

When I wanted to write about this painting I wanted to write about its composition and also the tension between the viewer of the painting and the viewer in the painting, whose view I am not privy to, but somewhere in the last five years I replaced my interest in what the painting does with what it depicts.

I was raised on and by poets who lived and died on the hill of William Carlos Williams’s credo that “a poem is a machine made of words,” meaning that a poem doesn’t represent anything other than itself because it is constituted of and inseparable from the occasion of its composition, i.e., it only means it made itself. But all of human experience is machine(s) made of words, since most of what we perceive is by expectation—we use math and language to map a world that we then confuse with the map. Now that we are handing that map off to the actual machines, it’s time to double down on looking about us seeing.

Something terrible has happened and is about to and I’ve all but ceased to see to see, that crucial capacity that Dickinson evinces then loses in her most harrowing death scene. It is double vision that I and we, the poets, need to employ like mad to keep us distinguishable from the machines.

I’m afraid that art is over, which is why, I believe, I can’t write. But a small wonder of the English language is that “I’m afraid” can express fear that something might be the case or state dolefully that it is already is. Even I don’t always know in which way I mean it. It leaves a little room to be uncertain in.

Here grass, shade, metallic disc of sunlit sea—

Never center your horizon!

Cormorant. Red nun. Whitecaps.

__________________________________

Paradoxx by Kate Colby is available from the Essay Press.

Kate Colby

Kate Colby has published eight books of poetry and prose, including The Arrangements (Four Way Books) and Dream of the Trenches (Noemi Press). She lives in Providence, Rhode Island.