A Tribute to Roberto Calasso

Friends and Colleagues Remember the Late Writer and Legendary Publisher

At the American Academy of Arts and Letters, where Roberto Calasso was elected as a Foreign Honorary Member, he is tickled by composer Charles Ives’ daily schedule which includes time for loafing after lunch as well as smoking and talking after dinner. 21 May 2015, New York City. Photo by Rachel Cobb. ©RachelCobb2015

Roberto Calasso is gone. Novelist, critic, scholar, and one of the greatest literary publishers of the last 50 years, the world of letters is diminished with his passing. I will always cherish the times I spent with Roberto at various books fairs and conferences around the world discussing books and authors and the challenging business of independent publishing, the conversations always concluding with how fortunate we were to engage in this enterprise. At the last London Book Fair we both attended the Canongate dinner and were leaving together when Roberto said “Let’s have one last drink,” so we followed the crowd downstairs to the dancing, Roberto propped himself at the corner of bar and ordered a gin and tonic. He surveyed the young publishing crowd pouring in and waved his arm at the scene and said “Isn’t it marvelous?” Yes, Roberto it was marvelous.

What follows are a few remembrances from some of Roberto’s friends around the world.

–Morgan Entrekin, Publisher and CEO of Grove Atlantic

*

I first met Roberto in the 1980s, at the home of Roger Straus. The guests that evening included Alberto Moravia and his wife Carmen Llera and Edna O’Brien—Roger’s pals—and Calasso was very much at home with them, a live wire, allegro and mischievous. Though a generation younger than Roger, he was already a longstanding member of the happy few club of international publishers, self-selected literary grandees still sailing along on the fumes of their authors’ reputations. Their enjoyment of each other and of the work they did, were both intimidating and infectious.

Calasso by then had been cutting a wide swath in Italian publishing for a good twenty-five years. He’d joined Adelphi, a scholarly house founded by a pair of friends, as the name implies, in the early sixties, and had brought it great energy and panache, eventually making it his own, by following the advice of the company’s legendary founding guru and guiding spirit Roberto (Bobi) Bazlen: to publish “only books we really like.” The books Roberto really liked were literary—far-flung, sophisticated, and above all, written—and Adelphi came to have a major impact on the Italian scene. Fashionable Milanese ladies had tables in their salotti that fairly groaned with Adelphi titles dressed in their elegant, severe covers. Some said they were the only books they read.

Being a latecomer to the party, as the new kid on the block is, Calasso knew that best-selling writers like Moravia and Morante, Calvino and Eco were out of range for a company with shallow pockets like his. He went searching elsewhere, notably in Bazlen’s beloved Mitteleuropa, and made hay with authors like Joseph Roth, Elias Canetti, and Milan Kundera. It was said he preferred his authors posthumous, and he had huge successes with, for instance, Georges Simenon’s Maigret novels which had been languishing in someone else’s warehouse. It was a matter of attitude and finesse, “sprezzatura,” the Italians call it—in the service of a cosmopolitan understanding of literature as a conversation across cultures and generations. And it could be great commerce. too. To see Roberto at the Suhrkamp Verlag luncheon during the Frankfurt book fair fielding offers for Sandor Marai’s Embers, a romance about pre-WWI Austro-Hungarian chivalry which he made into a world-wide bestseller, was to understand how far an astute nose and a pitch-perfect sense of style could take a canny publisher.

At Frankfurt, he would show up at FSG’s minuscule booth late in the afternoon, dressed in the typical Italian bourgeois’ Anglophile uniform of tweed jacket and flannels, looking for all the world like the rumpled professor he could easily have been. He’d pore through our future lists hunting for writers who could strike sparks on his eclectic but always coherent list. Many of our American offerings didn’t quite fit, or were already sold; his own recommendations, repeated year after year, tended to focus on Italian writers of great quality—Campo, Ceronetti, Manganelli, Ortese—who were usually too “specialized,” i.e., too profoundly Italian, for our readership, though we tried a few. No matter; it was the hunt, the excitement aroused by the author’s inimitable voice, that drove the conversation.

As it did with Roger, Roberto’s natural competitiveness could have a dampening effect on his camaraderie with homegrown colleagues—something that has been one of the joys of our trade for my generation. Their true peers, they felt, were elsewhere, in other countries and other eras. More than anyone, Calasso understood the eternal simultaneity of literature, how the conversation remains ongoing—the major theme, in fact, of his own prodigious books which make up a masterly multi-volume investigation into Greek and Indian and Hebrew myth, Kafka and Tiepolo and Baudelaire—which is dedicated to teasing out the enduring presence of the divine, the uncanny, the inexplicable in human art and life. The gods, as he called them, are always present in Calasso’s world, projections of our immortal needs and desires and aspirations.

My last communication from Roberto arrived in early July—two short books just issued by Adelphi. Bobi is a trenchant memoir of his old mentor and of his early years as a publisher. The other, Meme’ Scianca, written for his children, describes his own boyhood in an anti-fascist household in wartime Florence, perhaps his most personal and self-revealing work. I was unaware, as I have since learned, that Roberto had been ill, but the fervor and speed with which these books seem to have been written suggests that he was racing against time to have his final say.

At the back of Adelphi’s paperbacks, their perfect design unchanged for decades now, is a list of recently published titles. Among the latest 250—the whole extends to close to 800—are books by writers from Marina Tsvetaeva to Oliver Sacks, from John McPhee to Curzio Malaparte, from Alexander Pope to Thomas Bernhard. A few of the books that Roberto really liked—for the Adelphi list bears the unmistakable mark of the breadth and the boundaries of his interests, which ranged from ancient religion to modern physics. It’s difficult indeed to imagine the world of letters without Roberto Calasso; but the books he championed, for all of us, were in the best of hands.

–Jonathan Galassi, President of Farrar Straus & Giroux

*

We are proud to announce that Dr. Roberto Calasso, former head and brain of the little independent publishing company Adelphi, in Milano, decided to join our Heaven publishing department on Cloud One, where he has undertaken the LfIR (List for Intelligent Readers). Dr. Calasso, an expert in many Gods, had to undergo a long interrogation before the Committee of Unchristian Activities because he is known on Earth as the author of books on Indian, pagan, Buddhistic, and other Non-Christian organizations. Furthermore, he has declared an interest in Hell because he is deeply convinced that more or less all information circulated about Hell is ideological misinterpretation, especially our thoughts about the hot climate in that region.

After arriving in his new offices at Officine Aleph, Dr. Calasso hired a blind Argentinian librarian as editor in chief, who was useless to all the other Departments of Heaven.

The first books on their list will be a new translation of the Gilgamesh and a commentary on the Koran, which Dr. Calasso will review himself because there is no other expert available.

–Michael Krüger, writer and former Publisher of Hanser, Munich

*

“This is the most talented publisher of this country and certainly the most intelligent one” said to me Guido Davico, then publisher at Einaudi when meeting Roberto for the first time in 1976 in the streets of Bologna during the fair. I had just started as rights director at Flammarion. A few months later we would meet again when he acquired the rights of Leonora Carrington’s En Bas and the wonderful Hearing Trumpet. I also treasure the visit we made together with Fleur to the Lithuanian author Baltrusaitis in Paris after he bought the rights of Metamorphoses.

When a few years later I moved to London to marry Christopher, the latter asked me to read the collection of stories by Tabucchi entitled Piccoli Equivoci Senza Importanza. I loved it but we hadn’t been married for long and Christopher was not so sure about my Italian reading (though I spoke it fluently!) so he asked me to call Roberto to get his view. His answer still makes me smile thirty-five years later: “In the desert of Italian writing today this is probably among the most possible ones.”

–Koukla MacLehose, literary scout and original founder of London Literary Scouting

*

The Indian writer and publisher Anuradha Roy, who met Roberto Calasso several times at the Jaipur Festival, remembers him as erudite and approachable.

He lived beautifully, he wrote like an angel, and he was the best publisher in Europe for decades alongside his friends Michael Krüger and Jorge Herralde.

His catalogue, which was also erudite and approachable, was always flawlessly elegant, enviable and a lesson to us all.

–Christopher MacLehose, Publisher of Mountain Leopard Press

*

Roberto Calasso was a rare personality who unlike anyone before him managed to combine to the perfection the skills of publisher, critic, and novelist.

We were both exact contemporaries, two “toddlers” in the early seventies pacing up and down the alleys of the Frankfurt Book Fair, impatient to learn the secrets of the trade and eager to meet the stars and experts of the profession. Bumping often into each other, we were soon to become friends and accomplices, making sure to sit down to compare our notes and exchange our finds, at dinners and for a few years at our special Sunday lunch in company of other foreign favorite counterparts—discussing passionately the authors we loved and those we shared, like for instance our beloved Joseph Roth.

Roberto was warm, witty, immensely learned—a modern version of the “Man of the Renaissance,” wishing to share his erudition and simply great fun. Also capable of unexpected and endearing gestures. Aware of my great fondness for a spot in Tuscany, near the city of Pienza, where I rushed every summer, he came once at the end of the Fair with a present: the two volumes, published by Adelphi of the Commentarii by Aeneas Silvio Piccolomini, a renowned diplomat of the 15th century, later known as Pope Pio the Second, who founded the ideal city of Pienza in order (it is said) to keep an eye on his Cardinals in residence.

Hence the way I wish to remember Roberto, apart from his huge literary and editorial talents: as a considerate and generous friend.

–Anne Freyer-Mauthner, Editor in charge of foreign literature at Editions du Seuil, Paris

*

Roberto Calasso’s passing deprives us of maybe the most significant, illustrious publisher of our times. I first met Roberto in 1971 or 1972, when I had just begun my tenure as director of holdings at IFI, the holding company of the Agnelli family. Gianni Agnelli had recently acquired several Italian publishers, including Adelphi. I met Roberto, who though very young had already gained international recognition for his work in Italian publishing and whose name had become synonymous with Adelphi, a jewel of the publishing world. I liked him a lot right away because he ran his publishing house with not only literary flair and success, but also financial savvy. I always remember him saying that publishing good books wasn’t at odds with profitability.

As I got to know him, I came to appreciate enormously both his toughness and his eclectic, affable personality. When I spoke to him last just a few months ago, he sounded well and sharp as ever. He sent me a book he had just published, Come Ordinare una Biblioteca (How to Organize a Library), and I marveled at how diverse his interests remained in his eighth decade. Throughout his brilliant career, he brought us a wealth of beautifully packaged titles each more fascinating than the last.

We have lost a champion of letters and will miss him very much.

–Alberto Vitale, former Chairman and CEO of Random House Inc.

*

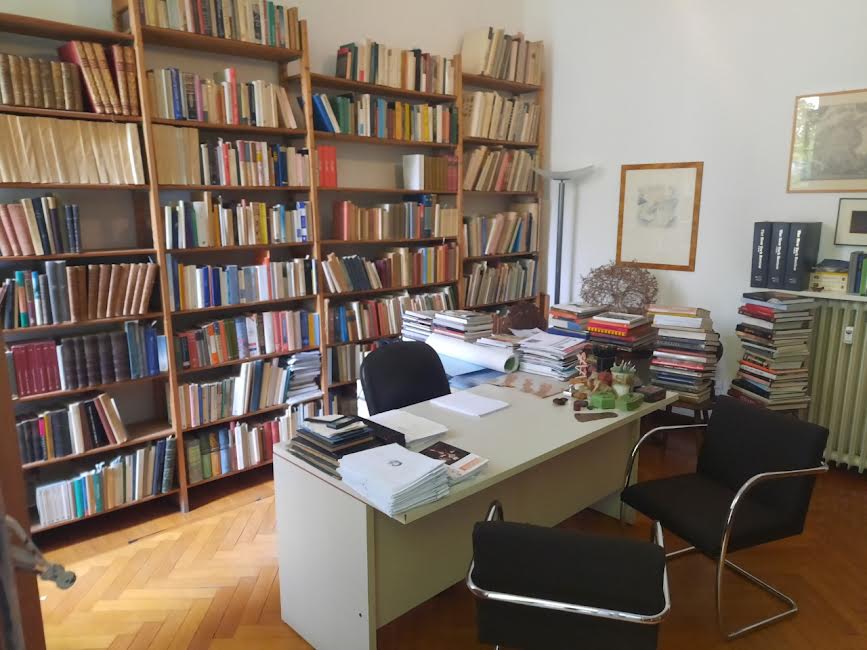

Roberto’s office at Adelphi. I was there yesterday to say a last goodbye.

–Carlo Feltrinelli

*

Jorge Herralde had asked us to join him in Santander for a weekend devoted to “independent publishing.”

Each of us was to deliver a speech on the subject of his choice.

When it was time for Roberto’s, the alcalde informed us that the conference would take place at the city theater. A bus would drive us there at four in the afternoon. There would be a cocktail party at the Yachting Club afterwards.

On stage, Roberto addressed us in English before switching to Italian—for which he apologized. “The subject of this conference,” he said, “is the following: WHAT IS A GREAT PUBLISHER?”

I couldn’t believe my ears.

Roberto had always been aware of his prodigious talents, but wasn’t it a little too much? Did he seriously consider paying a tribute to himself?

He began speaking, and after a while I realized my mistake—insofar as I was able to find my way through the maze of his formidable erudition. Roberto was talking about Alde Manuce, the famous Venetian publisher (and printer) who lived in Venice during the Quattrocento.

Shame on me.

While I had unfairly suspected him of gloating, Roberto actually taught us a great lesson in humility. For who among us could pretend to outdo the publisher of the legendary Hypterotomachia Poliphili

Later at the Yachting Club, over martinis, I confessed to him.

Roberto gave me a friendly look. “Je suis mégalomane,” he said. “Mais tout le monde ici est au courant, non?”

Then we laughed.

–Olivier Cohen, Founder and Publisher of Éditions de l’Olivier

*

The first time I met Roberto Calasso was in his Adelphi office in Milan. Early nineties.

I was there in the hope of persuading him to buy the Italian rights to Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder. The Norwegian writer’s novel about the history of philosophy had recently become a big unexpected success for Hanser in Germany, and several publishers in Italy and elsewhere were interested and prepared to make offers. Back home in Oslo, at Aschehoug, we were flattered and bewildered, unused to this level of courting from abroad.

However, in Italy, my meager knowledge of the publishing scene had pointed me to Adelphi. Their list and reputation seemed unparalleled. So, putting the bigger Italian contenders on hold, I approached Calasso. He was gracious, but I remember becoming slightly annoyed that he seemed more interested in talking about where I came from and how I lived than in the book I was there to sell him. Finally, a few weeks later, he sent me a letter, thanking me for having come to Milan in order to visit him, asking about my house by the sea and, almost as an afterthought, adding that he would not be offering for the book.

I have no idea if he ever read it or was just conveying an editorial decision. Most probably my pitch had been unconvincing. It doesn’t matter—Longanesi went on to make the novel a bestseller in Italy too.

Over the next thirty years we met regularly at literary events and book fairs. Regardless of the topics we were talking about he always made sure to inquire, “How is your house on the island?” “Good,” I’d reply, “you should come visit someday.” “I will, I hope to,” he’d assure me. And then we spoke about living by the sea, and he usually found reason to invoke literary and philosophical references to underscore his thoughts. In the first years they invariably led him to deplore his rejection of Sophie’s World, which in the meantime had become quite a commercial phenomenon globally.

But gradually, Roberto lost interest. Not in my living conditions, but in whatever reasons he’d had for turning down a novel about philosophy. My home and its landscape remained a fantasy that he would nurture every time we met. He’d never seen the place, but I know he imagined and re-imagined it, and somehow longed for it.

Seeing him through the lens of those visions, I can now picture him in the mythical place he’d gradually carved for himself. An ageless site from where he could contemplate and ponder the unyielding forces of earth and wind and sea in ceaseless combat with the majesty of the human mind.

–Halfdan W. Freihow, Editor Cappelen Damm

*

His qualities always baffled me and his faults always amused me. His qualities? An extraordinary curiosity, not limited—like in us common mortals—to narrow familial or professional interests. No: it was an omnivorous curiosity which was rarely satiated. Everything could become the object of a passionate exploration. Who had been invited to a dinner, what Milan Kundera had said that day, whether Yasmina Reza was present at a first in Berlin, which cocktail was being drunk these days in Paris, whether there existed undiscovered writings of Simone Weil. His faults? From when he was young, he had a reputation for being erudite, presumptuous, cold, unfriendly. This was a facade and it was easily chipped away when he came into contact with friendship, originality, novelty—all things to which he was extremely sensitive

For him publishing was a job built on relationships. The editor was a neurological junction and publishing was built on putting ideas in contact with people, people with places, places with books, and so on in an eternally intertwined back and forth. Publishing as he conceptualized it was an immense spiderweb woven with extreme care. Each book was a tile in a mosaic and no book that he chose to publish could be useless or provoke indifference. A proud ambition animated his career and every detail was important.

Two memories: when I was about to publish The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony in France, I called Roberto to tell him that I’d seen a small and very pretty painting in an antique store that depicted Cadmus holding up Harmony, with an azure and pink sky in the background. He took the train, came to see it, bought the painting, and thus was born the cover of the book that ended up becoming his bestselling one worldwide. A “difficult” bestseller, like he loved them. I think back also on the announcement of the Nobel prize for Elias Canetti: I was in Francoforte at Roberto’s stand, facing him; I saw his pure joy for the victory of a writer who he admired and published, one who had also become a friend and colleague.

We will miss publishers who have such an ardent and combative view of their trade.

–Teresa Cremisi, former publisher in Italy and France and CEO of Flammarion; currently editor of French literature and columnist

*

Roberto Calasso, a gracious thinker, was also a gracious publisher. Why he thought Adelphi, that august house, should publish my comic, romantic novel The Love Letter, I will never understand. But he did, with a pink cover playing on , the Italian term for a romance novel. And then, I later discovered, like the enchanting sorcerer he was, he charmed the booksellers of Italy and their customers into reading it. His authority, creativity and charisma as a publisher gave me a literary life in Italy for which I hope I thanked him enough.

When I flew to Milan, I was expecting to feel intimidated, an ignorant American dullard in the presence of European cultural elegance and intellectual majesty. Americans in publishing had tried to explain the exalted standing of Adelphi to me, I had read The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony almost breathlessly, with the excitement one imagines surfers feel riding a wave, and I felt, as writers almost always feel, I suspect, like a poseur who had stumbled on some mighty good luck and must not be found out by the eminent scholar. The man I met was instead a quick, stylish fellow, almost giddy with our joint success, who lugged my suitcase and me around with energy and humor, schmoozing in a comfortable, intelligent way that put me completely at my ease. I don’t know if this is the Roberto Calasso everyone remembers. Powerful people are complicated beings. But I, like all the booksellers hawking my pink novel, was utterly in his thrall. I cannot imagine a world where he is not thinking in ways no one else thought to think and writing it all down for us.

–Cathleen Schine, author of The Grammarians

*

Roberto Calasso was always a mythical figure to me, even after I met him and we became friends.

I’m pretty certain it was at a Frankfurt Book Fair in the late nineties and I’m pretty certain it was Morgan Entrekin who introduced us. I knew of Roberto prior to this because of his writing and specifically The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, his magnificent book on Greek mythology. What I hadn’t appreciated when we first met was what a brilliant, inspirational, careful, caring and completely uncompromising publisher he was.

The publishing house he was inextricably linked to was Adelphi which he joined aged nineteen and never left. He didn’t need to because he helped make Adelphi one of the most admired and successful independent publishing houses in the world.

I found Roberto intimidating when we first met. Part of me always did because intellectually he was orbiting me at such a distance. And even being called a publisher made me feel like an imposter of sorts when compared to Roberto—for Roberto was the real deal, a publisher who was fluent in half a dozen languages, whose knowledge extended into so many areas it made me dizzy, whose appreciation of art, film, politics and culture was so refined, whose understanding of publishing was so subtle and nuanced.

But his erudition rarely shrouded his impish and maverick qualities, his mischievous sense of humour, his insatiable curiosity, his openness to new ideas. He was great company because he could discourse on such a wide range of subjects and he was refreshingly down to earth considering how high-minded he could have been. And he was a true Epicurean.

One of my favourite Calasso stories, one I remember him telling me with great glee and gusto, is how he came to publish Sandor Marai, the Hungarian writer whose novel Embers became a global sensation twenty or so years ago and almost sixty years after it was first published. Roberto was in Paris, browsing in a second-hand bookshop when he came across a French translation of Embers from the 1950s. He didn’t know the novel but he thought it looked very interesting so he bought and read it. And he liked it so much that he contacted a Hungarian friend and asked him to read the novel in its original language as he wanted to get it translated into Italian. It was only when his friend alerted him to the fact that this French translation had taken terrible liberties with the original that Roberto realised the novel was even better than he had initially thought. So he acquired world rights in the novel, made the book a huge bestseller in Italy and proceeded to license it all around the world (it was translated beautifully into the English language by Carol Janeway) and it became a global bestseller as did a number of Marai’s other books which Roberto went on to publish.

In his own subsequent book, The Art of the Publisher, Roberto shares many of his insights and thoughts on the complex business and art that is making books, and since his death I have been rereading this seminal book and I have been hearing his unmistakable voice and it has been making me sad because I am never going to be in his presence again and I am never going to see his animated face and bright eyes or hear his wicked laugh. But I will never forget Roberto as long as I live because he made a huge mark on me, both as a reader and as a publisher. And I think he was one of the greatest publishers ever and I feel so lucky to have come into his orbit all the times that I did.

Thank you Roberto for brightening my world. And guiding me in ways that I only partially understand.

–Jamie Byng, CEO and Publisher of Canongate Books

__________________________________________________________

Head here for more on the life of Roberto Calasso (1941-2021)