A Taxonomy of Nonfiction;

Or the Pleasures of Precision

Karen Babine on the Peculiarities of Genre, Form, and More

I’m agate-hunting with my nine-year-old niece on the shores of Lake Superior, north of Duluth. It’s morning, the beach faces east, and there’s enough wave action to get the rocks wet, but not us. Agates are best spotted when they’re wet, my niece’s rock hunting book tells us. Cora holds up stone after stone: is this an agate? No, not that one. Our goal is to find enough agates to create a Lake Superior Mancala game.

We’ve been rock hunting since she was very small and each year we get more specific. One year: It’s a rock. The next year, we ask Is it igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic? Granite, rhyolite, or quartz? When I was a kid, we learned a mnemonic for the scientific orders—kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species—with a particular Minnesotan flair: Kirby Puckett Crushed Our Final Grand Slam and I loved the clarity of it.

Ask any writer or reader how they organize their shelves and you’ll get a glimpse into the way their mind works. I’m fascinated by the idea of a taxonomy in nonfiction, of order, an ever-expanding vocabulary to articulate what the page is doing. I’m not in pursuit of definition so much as I am seeking articulation. Marya Hornbacher writes:

The world is not vague. The world is extraordinarily precise. One of the tasks of nonfiction is simply to pay close attention to that world, and to record what we observe with precision and accuracy. […]

As a reader, I don’t turn to nonfiction to hear, for example, that summer is hot. I turn to nonfiction to learn how hot, what kind of hot? Are we talking California autumn hot, which smells of eucalyptus and fire? Or Minnesota August hot, which smells of melted road tar and fish? Which summer is this, hot to what degree, how does this writer know, why should I believe them, why should I care, what can they tell me about the world?

My high school science teacher once taught us the difference between accuracy and precision: he said that precision is a measure of the tool, accuracy a measure of the human. I am in pursuit of precision—which is not to say the shape of the tool, or its sharpness, can’t change. What the humans do with the tool is a different conversation entirely.

*

Genre

Genre contains the major groups of creative writing: fiction, poetry, nonfiction, drama. Some argue that genre doesn’t exist and I don’t agree. Ask any teacher whose students refer to all books—regardless of genre—as novels. Or all short pieces as short stories. Or all not-fiction prose as articles. What we call things matters. To my mind, hybrids do not exist as a genre: hybrids are simply how we add new vocabulary to what aspects of a genre, or a form, are load bearing?—how far you can get from a pantoum before it’s not a pantoum anymore?

Imprecision does memoir a disservice when memoir becomes the catch-all term for any personal nonfiction containing narrative or the first-person pronoun.

As a result, we have vocabulary to talk about Lee Ann Roripaugh’s Dandarians (poetry? lyric essay?) in a way we didn’t have in 2012. In the end, it’s not the classification itself that’s important. The more interesting conversation is what it’s doing—and how it’s doing it.

Subgenre

Subgenre is the field of knowledge in which the writer stands. Subgenre, which can be found across genre, is defined by content and includes travel, nature, science, food, historical, etc. It can be used as an adjective to form: historical journalism, travel flash, science memoir. Subgenre creates a lens: a subject like death or grief can be explored through a subgenre like food, like I did in All the Wild Hungers, or chemistry, like Oliver Sacks’ “My Periodic Table,” or falconry in Helen MacDonald’s H is for Hawk.

Form

Forms have definable edges. This isn’t to say that forms have rules, but they do have parameters, and those can be structural as well as rhetorical. (Certainly they can be arbitrary and confusing: is this a short story or a novella? A novella or a novel?) In nonfiction, form includes personal essays, classical essays, lyric essays, longform, flash, hermit crab, memoir, immersion journalism, literary journalism, experimental, etc. This level of classification is equivalent to the villanelle or sonnet in poetry, the novella or short story in fiction.

I strongly believe that the essay is a form, not a genre. I lay this taxonomic imprecision at the feet of Best American Essays, which contains many more forms than just essays. John D’Agata, among others, has frequently called the essay a genre, but I do not agree. Similarly, memoir does not operate on the same taxonomic level as fiction, poetry, drama, and nonfiction. Richard Hoffman, in “The Ninth Letter of the Alphabet,” calls the memoir a subgenre of the novel, which is taxonomically interesting, considering Irish critic Derek Hand makes a similar argument in A History of the Irish Novel.

Here’s why I care so much: recently, I was invited to speak about All the Wild Hungers with a community memoir class and I hesitated: if you’re going to judge All the Wild Hungers as a memoir, it’s going to fail, because it’s not a very good memoir, because I wrote it as a book of micro-essays.

That said, if she believes it’s a memoir, I’d love to hear why she thinks so. Imprecision does memoir a disservice when memoir becomes the catch-all term for any personal nonfiction containing narrative or the first-person pronoun. To lump them all together muddles the particular genius of each form.

Mode

The driving feature of mode is this: what creates the energy and engine in the piece?

If it is story that propels the page, its mode is narrative.

If the energy is language, it is lyric.

If the momentum is created by the writer’s brain, the mode is assay.

“Assay” means to test the quality or content of metal or ore, and this is the basis of Assay Mode. In an interview with Electric Literature, John D’Agata said, “I like to think of the essay as an art form that tracks the evolution of consciousness as it rolls over the folds of a new idea, memory, or emotion. What I’ve always appreciated about the essay is the feeling that it gives me that it’s capturing that activity of human thought in real time.”

Assay Mode, the “activity of human thought in real time,” drives classical essays like Hazlitt’s “On the Pleasures of Hating” or Charles Lamb’s “A Dissertation Upon Roast Pig.” Jordan K. Thomas’ “The Murder of Crows” moves in and out of linguistic and cultural and racial associations with crows—and while the language itself is part of the work, it’s Thomas’ mind that is creating the energy that moves the essay.

Narrative Mode draws its energy from the movement of story, of plot. Nellie Bly’s “Ten Days in a Madhouse” is immersion journalism in form, narrative in Mode. Bly’s narrative is the engine that drives her page. Donald Morrill’s The Untouched Minutes, which won the 2004 River Teeth Nonfiction Prize, is memoir in form, narrative in Mode, and A Day in the Life in Shape (discussed further in a moment).

I wondered if all memoirs are always in Narrative Mode, but a friend argued that books like Morrill’s, or Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, or Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House, are memoirs in Assay Mode. That’s the fun of this entire taxonomic pursuit: it’s not a matter of being definitive. It’s about starting a conversation.

Lyric Mode creates energy through the layering of language. Kathy Fish’s “Collective Nouns for Humans in the Wild” contains none of the story necessary for Narrative Mode; the author does not explore the inner workings of her mind in Assay Mode. Through Lyric Mode, Fish creates the deep, unspeakable-ness of yet more children slaughtered in yet another school shooting.

Our goal is not to be definitive, but to articulate what we see in a page.

Clearly Lyric Mode is not an invention of the 21st century or Western nonfiction: both Basho’s Narrow Road to the Deep North and Sei Shonagan’s Pillow Book work in Lyric Mode, because the fuel in their engines is language, the arrangement of Basho’s haibun, the inflections inherent in Shonagan’s kanji.

Lyric Mode can also have labyrinthine movement. Heidi Czerwiec writes in “Success in Circuit: The Essay as Labyrinth,” “…there are essays that are circuitous, nonlinear, that spiral around a central concept or incident or image, accruing meaning as they move. No forks, no false moves, no misdirection, only perhaps a pleasant disorientation as the writing twists and turns.” Brian Doyle is a master of the labyrinthine, particularly in “Joyas Voladoras.”

Czerwiec concludes: “[A] labyrinth … uses its repetitions with variations, its circuitous patterning, to delight and disorient but lead us, turning and leaping, in its ritual dance around its center.” Forms driven by Lyric Mode still need a center—and the center always holds.

Shape

Shape is a concept I’ve adapted to nonfiction from Jerome Stern’s Making Shapely Fiction, in which he identifies the shapes of stories we tell.

Stern’s “Juggling” is a story shape in which the internal action of the protagonist doesn’t match her external actions. Maria Isabel Alvarez’s “Strawberry Girl: A Prose Sestina” is a good prose example (whether it’s fiction or nonfiction is another conversation entirely). “Onion” is a Shape in which layers compress the author. Joy Castro’s “Grip” is a lovely Onion. J. Drew Lanham’s “Birding While Black” is an excellent short example of “A Day in the Life”; in book-length, Donald Morrill’s The Untouched Minutes uses the finite time-space of the home invasion for its shape.

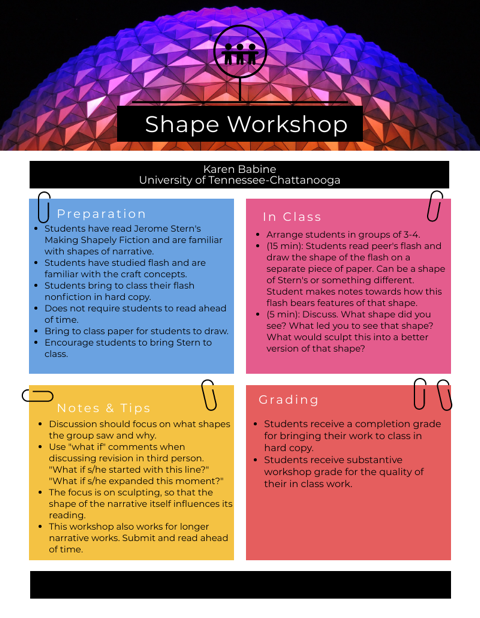

In my flash nonfiction class, we workshop a student’s draft-in-progress and allow the group members to decide which shape their classmate’s flash most closely resembles. Maybe it’s a Bear at the Door, maybe it’s an Iceberg. If the text doesn’t match Stern’s shapes, students are free to invent their own. Our goal is not to be definitive, but to articulate what we see in a page. At this stage, my students largely function on instinct. The conversations sparked by taxonomy move towards turning that instinct into knowledge, towards a precision of thought.

Against Taxonomy

I want to close with an argument against the impulse to get so specific as to lose the forest for the trees. My niece comes to visit and spies the Mancala on my shelf. At this moment, it doesn’t matter what the stones are. What matters is how we move them around the board and the time we spend together.

Karen Babine

Karen Babine is the author of All the Wild Hungers: A Season of Cooking and Cancer (Milkweed Editions, 2019) and Water and What We Know: Following the Roots of a Northern Life (University of Minnesota, 2015), both winners of the Minnesota Book Award for memoir/creative nonfiction. She also edits Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies. Her work has appeared in such journals as Brevity, River Teeth, North American Review, Slag Glass City, Sweet. She is an assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Tennessee-Chattanooga. Find her on Twitter , Instagram, and online at www.karenbabine.com.