A Tale of Two Sylvias: On the Letters Cover Controversy

What Do We Look For in a Literary Icon?

I leave my house wearing a baby blue wrap skirt, ankle socks, and two-tone oxfords. It’s mild for early summer, my bare legs paired with a sweater: champagne angora that frizzes an inch off each shoulder.

I’m headed to the community writing school behind the bagel shop where I’m teaching The Art of Character. Before I left, as I’d wrapped my hips in the skirt and tucked in the sleeveless collared blouse, I thought about dress: professional enough to be taken seriously, casual enough to look like myself. Clean, pressed. Nothing too low-cut. I thought, as I often think, that my male peers don’t worry about this, don’t need their outfits to prove authority. They look like they always look: breezy and indifferent in collared shirts or t-shirts and jeans.

As soon as I hit the main street, I run into someone I know from the English department. We say our hellos, and then he asks, “Where are you going looking so wholesome?”

Wholesome! “I’m channeling The Bell Jar,” I say.

“Right.” He nods. “Very 1950s.” I watch the smile slip to his chin, as he realizes my implication.

While I’m laughing and he’s standing there, slightly disturbed, I recognize the twist I’m after in life and writing. It’s the feminist affect poet Cate Marvin calls “arsenic icing,” borrowing the phrase from Mary Robison. Surface level: sugar sweet. Poison hidden under pastel.

“So he accuses me of ‘struggling for dominance’? Sorry, wrong number.”

−Sylvia Plath, May 15, 1952

Sylvia Plath has been on my mind all summer. I first hear about the October publication of never-before-seen Letters of Sylvia Plath (1940-1956) while visiting my hometown in Western Massachusetts and wandering around Smith College. I head to their Special Collections Library and am disappointed to learn it’s closed, for renovations.

Instead I thumb through my dog-eared Unabridged Journals, focusing on her first years at Smith: social anxiety around other women in her dorm; rigorous goals for publications and straight A’s; fears about losing her mind. I return to my own journals from this age and wince. Ambition coupled with strict standards. Self-punishment at any hint of failure. Plath dates often, with confidence in her beauty and anger at society’s double-standards: “hate, hate, hate the boys who can dispel sexual hunger freely, without misgiving, and be whole, while I drag out from date to date in soggy desire, always unfulfilled” (August 1950). A few days later, she writes, and Plath fans know this quote intimately: “If only I can find him . . . the man who will be intelligent, yet physically magnetic and personable. If I can offer that combination, why shouldn’t I expect it in a man?”

Weeks pass. I’m still lugging around her journals. My Ariel has lost its cover, poor naked spine. Re-reading Plath, I realize, isn’t merely a personal connection. It’s political. “You know, it doesn’t really matter what they write as long as you’ve got a young and beautiful piece of ass,” said Trump in the 90s, now emboldened even further, telling the French First Lady that she’s “in such good shape.” So I turn to Plath, who coos, rolled eyes: “Every woman adores a Fascist.”

Plath knew what it was like to be picked apart for meat: valued as legs or breasts or blonde hair. In July 1952, she suns herself in “aqua shorts and a white-and-aqua halter” and writes:

Outwardly, all one could see on passing by is a tan, long-legged girl in a white lawn chair. . . . To look at her, you couldn’t tell much: how in one short month of being alive she has begun and loved and lost a job. . . .won one of two $500 prizes in a national College Fiction Contest and received a delightful, encouraging letter from a well-known publisher. . . .To look at her, you might not guess that inside she is laughing and crying, at her own stupidities and luckiness, and at the strange enigmatic ways of the world which she will spend a lifetime trying to learn and understand.

Plath wrote with an awareness of the public, in her poems and journals. She worked damn hard to be famous. She idolized Virginia Woolf’s novels and diaries, both. And she certainly did worry about the overlap between her life and writing, but seemed to settle on curiosity. “The dialogue between my Writing and my Life is always in danger of becoming a slithering shifting of responsibility . . . I justified the mess I made of life by saying I’d give it order, form beauty, writing about it; I justified my writing by saying it would be published, give me life (and prestige to life). Now, you have to begin somewhere, and it might as well be with life” (February 1955). There is a danger in reading a life story over the poems and novel, themselves, but when you look at all the work at once, you’re met with an awareness of how this art could come from only one.

*

Courtesy of The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Courtesy of The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

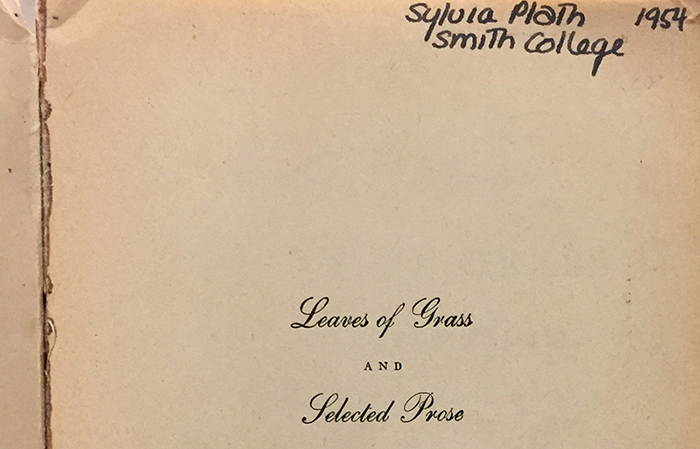

While getting my MFA at the University of Virginia, I’ve worked at the public services desk at the Small Special Collections Library, typing my favorite poets and writers into our search engine during my downtime. We hold eight books from Plath’s personal library, among them: Anna Karenina and Leaves of Grass. The first time I saw the “ex libris Sylvia Plath” sticker, the perfect posture of her “y” and “l,” her rounded v, the slight ink smudge along the h’s tail, I felt a giddy, privileged rush: my hands where hers had been. When I saw how much she’d marked up—underlining, exclamation points, comments, and quotations from other texts—the feeling was almost too much. I leaned forward to listen.

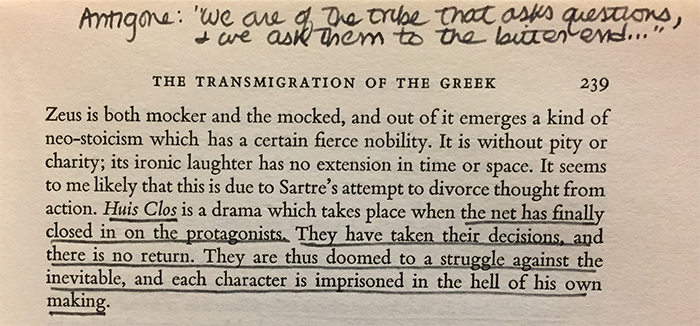

Plath makes craft notations: “bathos,” “vivid contrast,” “naturalistic detail.” She lists words she needs to look up, on back flaps—teaching us their definitions. There are funny margin notes. When Tolstoy’s Levin complains, hangry, about the empty dinner table “in a tone of vexation, ‘You might have left me something!’” she writes, “poor baby!”

There are troubling margin notes, too: suicidal ideation, pride in suffering. Deeply unsettling notes, knowing how sick she was. Whitman writes about suicide, and in the margins, Plath comments, “he doesn’t understand.” With Anna Karenina, in loopy script: “dream come true.” The teacher in me wonders about intervention, how she must have looked and seemed in class, gripping these books, just before her suicide attempt in summer 1953.

Courtesy of The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Courtesy of The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

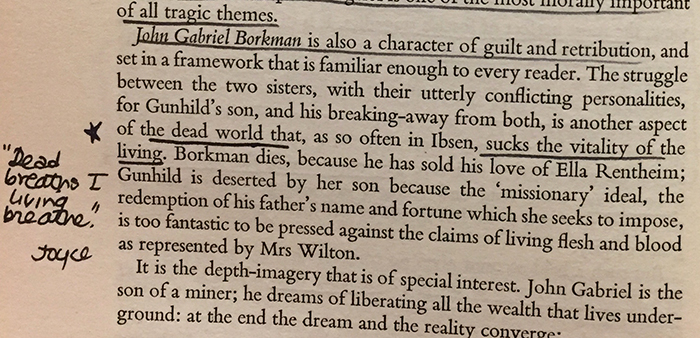

But the margin notes that strike me as most interesting point to Plath’s intellectual curiosity about her own dualities, leading to her thesis, “The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double.”

“All the variety, all the charm, all the beauty of life is made up of light and shadow,” Plath underlines and stars.

“How can you be so many women to so many people, oh you strange girl?”

−Sylvia Plath, August 22, 1952

It is with all this in mind that I encounter the cover art for The Letters, in July.

My first reaction on seeing the British edition is surprise, and then a smile, happy to see Plath’s dualities so neatly on display, across the two editions: summer, winter; blonde, brunette; light and shadow. On the left is the woman who dyed her hair platinum blonde—not on a whim, but to brighten her image, after her first suicide attempt and hospitalization. I’ve seen the photo before. It’s Plath’s “Marilyn shot,” taken by then-boyfriend Gordon Lameyer. Her mother Aurelia included the photo in the collection Letters Home. It’s also featured in the Smithsonian Exhibition, this summer, on Plath’s creation of her visual identity. Here’s the same woman, who, aware of what society sees when they look at her, dyes her hair dark while applying for the Fulbright. She was brilliant and beautiful, but in her lifetime, not allowed to be both.

Poet Kaveh Akbar tweets: “Burn all your swimwear photos, lest someone accidentally confuse one for a cover for your book of posthumously released letters.” A valid point, and one that resonates, liked by over 650 people. Still, I can’t let go of my gut instinct: it is a good thing to deepen the public perception of Sylvia Plath. This photo isn’t something she would’ve burned.

Darling, all night

I have been flickering, off, on, off, on.

−Sylvia Plath, Fever 103°

In mid-August, I teach ZZ Packer’s “Drinking Coffee Elsewhere” to a class of first and second years at the University of Virginia. We’re talking about narration, pinpointing Dina’s lexicon—how she tells her story, word choice, references, subtext, and register shifts. A student raises her hand. I walk over. Her finger taps the words “Sylvia Plath.”

“She’s the one who stuck her head in the oven, yeah?”

I breathe in. “She did commit suicide.” Then: “Why do you think Packer references her, here?” Even the narrator uses her as a throwaway joke: Don’t go all Sylvia Plath on me. Over and again we make the mistake of reading into her death a conclusion: that she was all despair, ignoring the funny poems, the sexy poems, the loving, maternal poems, the prismatic, all-encompassing poems.

I do think calling “male gaze” on the cover of Letters implies a certain level of pity: poor Sylvia, even in death, being paraded around for men. Yet we should not overlook the hyper-aware carnality of her work, her insistent control. Even in a poem like “Lady Lazarus”—in which Plath calls death “the big striptease” and brags about the “very large charge” for a glimpse at her scars—the tone is chirpy and flirtatious, with those trademark round vowels and confident, declarative lines. It’s this allure—delicious poison—that makes her poetry so powerful, so lasting. She is in control. She flirts you close enough to burn you.

I love Faber’s cover for what young women, especially the ones now beginning to write, will see: wide grin, toes dug into hot sand; an image of joy when they expect only suffering; relaxed and happy instead of buttoned-up, high art. I suspect they won’t see in this image a sex object, just as I do not. Rather, I recall the thrill she describes in her journals: the slow trickle of sweat; the heady pleasure of sun on bare skin.

And yet: is this the same side of me damned to preening myself into an image my students will take seriously? “To preen, for a woman, can never be just a pleasure,” Susan Sontag writes. “It is also a duty. It is her work.” How deeply engrained is it that to be taken seriously as a teacher, I need to look good, but not too good or else I’ll be deemed a flake? How contradictory, that my sex appeal and intellect cannot exist in the same body? Still?

What about the side of me, that like Plath, feels this gendered burden, hears again and again: “How will you make a living writing poems?” “I have a story you should write” “Have you published anywhere I’ve heard of?” “Who reads poetry? Give me your autograph, just in case.”

You’re demeaned for making art. “You do not do. You do not do.” In the off chance you succeed, they want the credit for making you.

*

Courtesy of The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Courtesy of The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

A month later, I’m still seeing double. I can’t talk to Plath, of course, but I can ask her poetic kin what they think. I reach out to poets I admire: ones I think are Plath fans, ones who have written about her outright, or who, in their poems, mix lightness and darkness, joy alongside sorrow. They’re daughters, descendants.

After some thought, I’ve found I am similarly of two minds. While it would be difficult—absurd, even—to imagine a scenario in which a male poet would be featured on a book cover in his swimsuit, this cover, and the photograph itself, doesn’t exist in an idealized vacuum devoid of sociocultural context. There’s much to be said about the male gaze and objectification of women’s bodies and whether or not women can challenge or co-opt established power dynamics by utilizing their sexuality. The influences at play when Sylvia had the photograph taken (her boyfriend would not have been expected to send her a series of swimsuit photographs, and very likely didn’t) and when Faber chose this photograph out of a number available are of course going to be, at least in part, shaped by a larger cultural context in which attractive women’s bodies are seen as valuable and representative of pleasure, desire, and vitality. It’s complex, and I think too much for me to parse through here.

So, that aside, I have to admit I have always loved Sylvia’s swimsuit photos. When I first stumbled across them years back, it was a relief. Perhaps that is a strange feeling to have, but Sylvia Plath has been transformed into an icon of despair and madness, a tragic cut-out as opposed to a multifaceted person, and I was glad to witness proof of what I knew in my heart: that she had lived a full life that included joy, with moments that didn’t call for seriousness or grief. There seems to be a tendency toward wanting to categorize women into two camps: either bright and serious (but not desirable) or fun and attractive (but not intelligent). Sylvia Plath in a turtleneck and coat is a predictable image, as it reinforces the (true) narrative of her as an intelligent, serious woman. What I enjoy about the swimsuit photo is that it upends the one-note myth of Sylvia—she was playful, and sexual, and took pleasure in her life, and she also ultimately ended that life. Her death should not be the sole lens through which we view and talk about her life. It’s dishonest, and lazy, and damaging. Whether or not Sylvia would have chosen this particular photo for her cover is not something I have an answer to. I’m not sure how I feel about the use of it as a cover, even after mulling it over so long. But the photograph itself, I can say, is one that I love, because it is one in which she is happy.

I wish none of Plath’s books had her image on the cover. I don’t generally like seeing author’s faces blown up on covers. I want to read the work, not look at the face. (Except Larry Levis because he’s so handsome.) But with Plath in particular I think putting her image on her books draws us once again to looking at her life over the work: which, I believe, is exactly what she would not have wanted us to do.

I like that the Faber cover defies reductive Plath stereotypes and shows her in a moment of joy. I feel protective of that joy; perhaps this book cover is meant to indicate that the letters therein are not by Plath as a received set of often sexist clichés, but by a real, whole person.

Is the Harper Collins cover, the image of Plath in a high-necked top, any more real? More intellectual? More serious? More… what? I mean, there is nothing inherently degrading about the image of a woman in a swimsuit, and this image in particular does not feel in service to the male gaze.

I do get how tired we are of sexist, objectifying book covers, of course I do, but a reflex negative reaction against this particular cover image feels incomplete to me.

I must admit: I actually groaned when I saw a tweet of the bikini cover. I like knowing, through your email, that she sent the photo to a boyfriend and dubbed it her “Marilyn photo.” But are we assuming that the publisher’s marketing department knew this, too? Is it cynical to believe that product packaging is meant to sell a product, and perhaps even meant to create buzz in order to do so? I have photos of myself in a swim suit, photos of myself dressed up for Halloween, and photos where I’m in my pajamas snuggling my children. They may reveal things about my private life and my sense of humor that a reader would find interesting, but do I use them on my book jackets or website? Would I want any of those photos on the cover of my posthumously published letters? No.

[NB: When I reached out for comment, the British publisher said there is a strict embargo on discussing anything about the Letters, until after its publication. The editor did mention, however, the importance that the cover image match the time period of the letters, therein.]

If Sylvia Plath were still alive, she would turn 85 this coming October, just five years younger than another iconic American poet, John Ashbery, who passed away at 90 this past week in September. Ashbery’s death got me browsing through my collection of his books and rummaging, in particular, for photographs and paintings of Ashbery, either on the covers of his and other people’s volumes, or elsewhere. I love the range of these portrayals, from the sexy image on the cover of his breakthrough book, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, shirt mostly unbuttoned, tight pants, a mash-up of Courbet’s The Desperate Man, Johnny Depp, and Geraldo Rivera. There is edgy Ashbery, aesthete in skinny tie and jacket, cross-legged and smoking with painters; professorial Ashbery in spectacles, sweater vest, and open collar. In other images, he presides, sphinx-like and monumental, like Gertrude Stein. I wonder if any of one of these various “versions” of Ashbery, if chosen as a cover for a collected works or letters, would italicize readers the way the two images of Sylvia have roiled her admirers.

And how can we guess, in retrospect, how Plath would have wanted to portray herself as we approach the end of the second decade of the twenty-first century? To paraphrase the poet A. R. Ammons, touch the universe anywhere, you touch it everywhere. Our reactions to those images must reveal much about ourselves, which is one of the great gifts of history, of literature, of art.

The saddest part is that Sylvia loved those “platinum” photos. They represented an expansive, independent time in her life—a time of creativity, confidence, good health and joy. But that’s not what the public sees. They see a blonde in a bikini who couldn’t possibly be a “writer.”

Male writers are allowed—even encouraged—to flaunt their masculinity. Look at photos of a young Arthur Miller in a Brando-style undershirt, sexy and sinewy behind his typewriter. Or Jack Kerouac with his sleeves rolled up, smoking a cigarette and flexing his biceps. Romantic era writers were depicted as rock stars—especially Byron and Shelley—all bedhead and rumpled shirts and smoldering gaze. Their sexuality was raw, obvious, aggressive—and no one questioned their intelligence because they were men. Everyone loves those shots of Hemingway—drunk, shirtless, holding a gun. So why can’t we show Sylvia Plath at her best—happy, healthy, enjoying a day at the beach?

As summer fades into the school year and the beaches go cold, I am grateful to Sylvia Plath, for opening this conversation with poets I admire, and for her poetry, sweet as arsenic icing, delicious poison.

Courtesy of The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Courtesy of The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

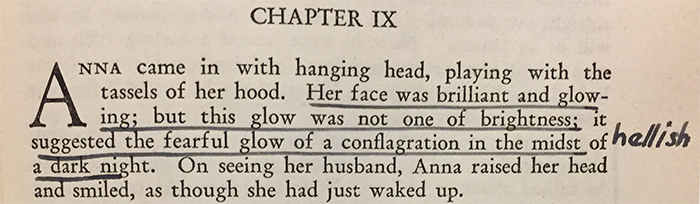

I look at the British cover again and remember one last margin note. “Hellish” Plath writes, next to Tolstoy’s description of Anna: “Her face was brilliant and glowing; but this glow was not one of brightness; it suggested the fearful glow of a conflagration in the midst of a dark night.”

In passing, you might see a pretty young woman on a beach. Hellish, I think. Here is Plath: conflagration in the midst of a dark night, bright and blinding. “Does not my heat astound you! And my light!”

Nichole LeFebvre

Nichole LeFebvre is a Poe/Faulkner Fellow at the University of Virginia, where she teaches creative writing, including a course on “Unearthing Fiction” at the Small Special Collections Library. Her poems can be found in Prairie Schooner and Barrelhouse and recent prose in Paper Darts and Vol. 1 Brooklyn. She is the Nonfiction Editor of Meridian: A Semi-Annual and is at work on a memoir.