“A Syrupy Love-Fest.” On the Blasphemous Disneyfication of Felix Salten’s Bambi

Jack Zipes on the Great Shame of Diluting Salten’s Message

One of the reasons Felix Salten had become famous was the translation of Bambi into English in 1928 by the American writer Whittaker Chambers (who, decades later, was revealed to be a communist spy). Chambers had a limited understanding of Austrian German and spent little time in Austria. Consequently, his translation is filled with all sorts of errors and fails to capture Salten’s unusual Viennese style of writing and anthropomorphism.

Moreover, he mistranslates many German idioms, omits phrases, and does not convey Salten’s profound personal and philosophical dilemma. Nonetheless, the translation became enormously popular: a foreword by the famous writer John Galsworthy, reviews in the New York Times and other newspapers, and the selection of Bambi by the Book of the Month Club lent the translation legitimacy.

As Sabine Strümper-Krobb points out in her astute essay with the unusual title “‘I Particularly Recommend It to Sportsmen,’ Bambi in America: The Rewriting of Felix Salten’s Bambi”:

the English translation actually tones down Salten’s anthropomorphism in places and changes its focus in others, thus opening the possibility for the story to be understood less as a human story about persecution, expulsion or assimilation and more as an animal story conveying a strong message about the protection of animals and the necessity of conservation. At the same time, while emphasizing the central universal message of the vulnerability of all life, animal or human, the slight shift in the way which Chambers deals with Salten’s anthropomorphism reduces the transcendental dimension that the original novel contains.

The mistakes Chambers made, however subtle they might seem, have had immense consequences for the interpretation and reception of the novel. Both the English translation of Bambi and Disney’s animated film, which appeared 14 years later, have done Salten a disservice. Of course, Salten did not care or understand whether his best-selling novel was competently translated. He was simply pleased that it brought him recognition and fame, which would give him the means later to escape the Nazis in 1939, after Austria had been annexed by Hitler’s troops and Austrian Nazis.

Salten, like many European Jews, found it incredible that he would have to leave Austria when he felt more Austrian than his fellow countrymen. Even when the Nazis banned Salten’s books in 1935 and it became clear that they would soon be marching into Vienna, Salten continued to support Austria’s right-wing, authoritarian government. Ultimately, after living several months under Nazi rule, he used his connections among the Austrian nobility and officials to obtain a permit to live in “neutral” Switzerland, where his only daughter, Anna, by then a well-known actress, had made her home.

Both the English translation of Bambi and Disney’s animated film, which appeared 14 years later, have done Salten a disservice.

When the Swiss government granted Salten and his wife permission to live in Zurich, one condition was that he would cease all activity as a journalist. He was permitted to write only books and plays, and he was not allowed to be active in cultural politics. Consequently, he published mostly animal stories, and they were not very profitable. Since he had sold the cinema rights for Bambi to the American director Sidney Franklin in 1933 for a mere $1,000, and since Franklin transferred the rights to the Disney Studios, Salten did not gain much from the success of the 1942 animated classic Bambi. Here and there, thanks to other contracts for his animal stories and the support of his daughter, Salten was able to live comfortably until his death in 1945. By this time, Salten had lost all sense of what was happening in the world. He was in a world of his own.

Although Salten may have grasped that Walt Disney had radically transformed his novel Bambi into a sweet family film when he watched the animated film in 1942 in Zurich, he had no idea that his name would gradually become detached, if not erased, from Bambi. Disney’s sentimental film became the sugary version of Bambi that most people have come to know, and most people continue to think that Disney created the Bambi story. Salten is a forgotten figure, except possibly in countries like Austria and Germany, but even there, Bambi has been Disneyfied.

In his informative and persuasive essay “The Trouble with Bambi: Walt Disney’s Bambi and the American Vision of Nature,” Ralph Nutts notes:

Bambi’s touted authenticity is severely limited. The film is faithful to visual, artistic accuracy in the general appearance and movements of many of its animals, not to a scientific or ecological accuracy. Even the visual accuracy is compromised for the sake of cuteness: for example, the more traditional cartoony cuteness of Thumper and Flower, and the tail-hanging opossums. In short, despite their efforts to be accurate, Salten’s original version of Bambi underwent a transformation as Disney and his staff reshaped it to fit a different medium, their own sensibilities, and a mass market. In the process much of Salten’s ecological and moral subtlety were winnowed away… The image of cuteness has become so popular that even adult deer are sometimes mistakenly shown with spots. Disney, however, had a well-tested technique for carrying cuteness to an extreme.

He had no idea that his name would gradually become detached, if not erased, from Bambi.

But Disney and his collaborators did far more than add cuteness: they transformed the novel into a syrupy love-fest that justifies male domination and power even as the film’s signature song, “Love Is a Song That Never Ends,” prods audiences to admire the forest as a utopia. As Donald Hall points out in his highly critical and insightful essay:

Bambi, created in the Disney studios of suburban Los Angeles, is a vehicle in the service of what social historian Mike Davis calls “the establishment,” in Southern California and across the nation of a “bourgeois utopia” during the period between 1920 and 1960. As we shall see, the process of creating this utopia involves playing with history in order finally to mark and tame a private territory, to create a domain surrounded by a defensible perimeter, allowing one to preserve and protect a communal “homogeneity of race, class, and . . . values.”

This is a great shame, for Salten’s novel is a brilliant and profound story of how minority groups throughout the world have been brutally treated, even when they try to live peacefully in their own environment. Read in the original language and in its sociohistorical context, Bambi is, if anything, dystopic and sobering, for it reveals the cutthroat manner in which powerless people are hunted and persecuted for sport. Salten was able to capture this existential quandary through a compassionate yet objective lens, using an innovative writing technique that few writers have ever been able to achieve.

Owing to Salten’s extraordinary empathetic composition, Bambi can be read on several levels: as a German Bildungsroman, or novel of education; an existentialist autobiography; and a defense of animal rights. Taken critically and seriously, Salten’s novel exposes the Disney Bambi as a shallow, sentimental film. Indeed, it shifts the emphasis of the narrative to glorify male elitism, and made numerous changes that other scholars have discussed at some length. More important, I believe, is a focus on just how relevant Salten’s novel still is.

_______________________________

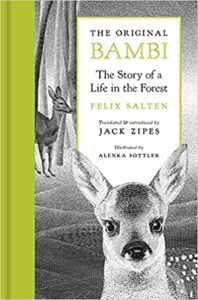

Excerpted with permission from The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest by Felix Salten, translated and with an introduction by Jack Zipes. Published by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved.

Jack Zipes

Jack Zipes is the author of The Irresistible Fairy Tale, translator of The Original Bambi and The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, and editor of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (all Princeton). He is professor emeritus of German and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota.