A Study in Contrasts: On Nannying and Implicit Trust

Zhang Yueran Explores How Her Child’s Nanny Sparked the Inspiration for Her New Novel

Translated by Jeremy Tiang.

I’ve always been interested in writing about nannies, perhaps because their existence is a study in contrasts. In China, a nanny’s life is difficult: usually she gets married and has children young, then leaves them behind to be looked after by her husband’s parents while she heads to a city in search of work. Apart from ten or so days around the New Year, a nanny remains away from her family, spending most of her time in her employer’s home. She’s adept at using high-end household appliances, knows how to iron expensive silk outfits, and can cook complex dishes. A nanny gets used to telling her boss, “We’re out of dish soap” or “We need to buy a new humidifier” as if she’s a part of the household.

Yet her real life might only begin late at night, when she lies her aching body down on a single mattress. Even then, her real life consists of a video call, a young child on her phone screen. “It’s Mama, say hello to Mama.” She must help her kid remember who she is, to fill in the empty space around this face in his mind. Only in these few minutes does she inhabit her true existence.

Jiao was different from other nannies in that she didn’t like to call the children she’d left behind. “It’s no use,” she said. I wasn’t sure if she meant useless to them or to her. What would she consider useful? In any case, this seemed to represent Jiao’s desire to enter more fully into the life before her eyes.

I knew that Jiao might leave us someday.

When she began working for us, my son was five. She came every afternoon. He immediately took to this auntie with the curved eyes and perpetual smile. Whenever she played with him, she threw herself into their games and seemed to be having a blast. Her party trick was making a robot out of scrap cardboard. To comfort my son when he burst into tears or to reward him for the slightest accomplishment, she’d conjure up a robot in the blink of an eye, like a magician, and present it to him. There were times when it made me a little worried—and a little jealous to be honest—to see them playing together so happily. I knew that Jiao might leave us someday.

When it actually happened, though, I could never have imagined the circumstances. It was a day in May, roughly two years after she started working for us and when my son was in kindergarten, that a police officer knocked on my door and told me Jiao had stolen a package from my next-door neighbor. I refused to believe him until he showed me the security footage. Later that day, another household where Jiao worked on weekends said things had gone missing from their apartment too. “I didn’t steal anything, I was just…” said Jiao haplessly as the police led her away.

In the days after this, I began recollecting things that had gone missing during the last few years, too insignificant to attract attention. For instance, my son’s stuffed toys, snacks that my friends gave me, a towel the shade of a purple yam, a straw hat… Low value items with nothing in common, which is why I hadn’t noticed they were gone. I recalled what Jiao had told me about her past: she’d had a happy childhood until she was twelve, when her doting mother drowned in the floodwaters that washed away their family home. Her father remarried a woman whose son bullied Jiao, ruining her nice stationery and so on. She had to hide her favorite things, but sometimes she did too good a job and couldn’t remember where she’d put them. When she told me this I said, but then you couldn’t enjoy these things yourself. That didn’t matter, Jiao shrugged, I felt good just knowing they were someplace else, because when I particularly liked something I wanted no one at all to have it.

During one of our arguments, at my wits’ end, I blurted out, “Jiao doesn’t even love you!”

A few months after Jiao left, I had to empty out our apartment in preparation for a move. Right at the back of a kitchen cabinet, I found a canvas bag stuffed to bursting with a curious assortment of objects: a glow-in-the-dark bouncy ball, a fridge magnet that said “Seville” in colorful letters, a hand mirror with an ornate frame carved with fritillaries, its glass shattered. I was certain these weren’t mine; she must have taken them from another household. So probably my missing possessions were in another apartment somewhere. Like a swallow leaving a hidden nest behind.

“I didn’t steal anything, I was just…” I remembered her saying as the police took her away. “I was just hiding them.” All these items that disappeared from our lives had given her a sense of something like spiritual ownership, expanding the narrow confines of her life. And perhaps she considered this “useful.”

I never deleted Jiao from my phone, and every now and then I’ll click on her WeChat page to see what she’s up to.

The main problem I needed to deal with was the hurt that her abrupt departure caused my son. For a very long time afterwards, he persistently begged me to go find Jiao and bring her home. More than once he emptied the display cabinet of all the cardboard robots she’d made for him and laid them out in rows, like a lonely monarch surveying the troops he and Jiao had once commanded together. Worse, he grew cold towards me because he believed I’d chased her away. Even if she’d done something naughty, he said, I shouldn’t have treated her like that. During one of our arguments, at my wits’ end, I blurted out, “Jiao doesn’t even love you!”

I knew right away I shouldn’t have said that. Looking back at her time with us, it was obvious that her affection for my son was real. Those words tormented me for a long time, and I felt guilty towards Jiao. Then one day, I realized I was writing a story about a nanny. It began with the complicated feelings this nanny, Yu Ling, feels towards Kuan Kuan, the little boy she’s looking after. The child trusts her implicitly, which makes her want to make use of that trust and turn it into something “useful,” but at the same time she can’t bear to betray that trust. Without her realizing it, the child’s love for her has become the most important thing in her life. I thought of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day, a novel I’m very fond of, and the heartbreaking moment when Stevens the butler learns that his employer has made a catastrophically bad life decision, laying waste to Stevens’s lifetime of hard work and service.

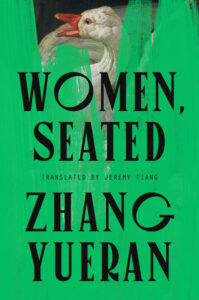

While writing my own novel, Women, Seated, I began to wonder whether in feeling sad for Stevens, I might have unwittingly accepted a masculine mode of storytelling. Might a story about a female domestic worker be different? If her main task is looking after a child, then no matter what happens, you couldn’t easily claim that all the attention she’s given to the child is ultimately meaningless. Kuan Kuan’s mother and Yu Ling would likewise have a different type of relationship; when they’re together, their bond might not appear as sturdy as between Stevens and his employer, but when facing the collapse of their value system, Yu Ling’s choices reflected how she valued the time they’ve shared and the connection they’ve forged.

From a certain point of view, The Remains of the Day is a novel that lends itself readily to abstraction, with the male roles fitting within an established symbol system to represent particular segments of society or ideologies. It would be difficult to so neatly abstract female relationships in the same way. As Lacan points out, women occupy a less clearly defined space within the symbolic order, and they are more likely to view the world through emotion and experience. Perhaps this allows relationships between women to be more humanistic and more dynamic.

I never deleted Jiao from my phone, and every now and then I’ll click on her WeChat page to see what she’s up to. Over a year ago, I noticed she’d returned to her hometown and was working in marketing for a company that made ceramic floor tiles. Soon after that, she began selling exquisite coasters made from leftover tile material. I ordered a few right away. When they arrived, I found an extra package with my son’s name on it. Inside was a robot made from cardboard scraps, rather travel-worn and with a smile on its face. I put it in the center of the display cabinet, and waited for my son to come home from school.

__________________________________

Women, Seated by Zhang Yueran and translated by Jeremy Tiang is available from Riverhead, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Zhang Yueran

Zhang Yueran is the award-winning author of several novels written in Chinese, including Cocoon, which was translated around the world and won the Best Asian Novel of the Prix Transfuge in 2019. She lives in Beijing.