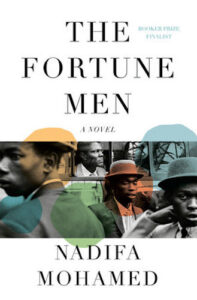

“A Story That Wouldn’t Let Me Go.” Nadifa Mohamed on the 1952 Case at the Heart of Her Novel

The Author of The Fortune Men Speaks With Jane Ciabattari

The Fortune Men is a finalist for the Booker award. The week of our email exchange between Nadifa Mohamed in London and my base in Sonoma County, it was announced that her novel also was shortlisted for the Costa award. She also has won the Betty Trask award and the Somerset Maugham award, and was named one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists in 2013. How have these recognition influenced her work? “I’m not sure is the honest answer. I think that every novel I try and write is a productive of so many conscious and subconscious concerns. I think that I want to keep on taking risks in what I write about and how, and prize nominations give you the feeling that you must have done something right with your last work and to keep pushing yourself.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How has the tumultuous time of pandemic been for you? Where have you been living? Have you been writing?

Nadifa Mohamed: I’ve been at home in London most of the time with just a few short escapes abroad. It has been extremely tumultuous, maybe the most tumultuous period in my life with big things—both good and not so good—happening. I have managed to write a little but more importantly the next novel has been coming together in my mind.

JC: When did you first hear of the 1952 case of Mahmood Mattan, convicted of the murder of a shopkeeper, the last man in Cardiff to be sentenced to death, and the first “wrongful execution” case in British criminal law history?

NM: I first read about him 17 years ago, after his conviction had been quashed.

The Fortune Men was a Somali term that my father had shared with me… it was used to refer to men like [Mahmood] who had gone to make their fortunes at sea, but I also liked that it could mean men who put their fate in fortune’s hands.

JC: What drew you to the story as the basis for your novel The Fortune Men?

NM: It was a story that wouldn’t let me go. I wanted to know why, what and how everything happened. The fact that my father knew him made it feel more familiar too, a way of examining the lives of all Somali sailors in Britain not just Mahmood’s.

JC: What is the meaning of the title?

NM: This was a difficult novel to settle on a title for, I went through so many. The Fortune Men was a Somali term that my father had shared with me while we were working on Black Mamba Boy. It was used to refer to men like him who had gone to make their fortunes at sea, but I also liked that it could mean men who put their fate in fortune’s hands.

JC: When listening to false testimony against him in the Law Courts, Mahmood scoffs: “They have created a man—no, a Frankenstein monster—and branded it with his name before setting it loose…he feels the blows of their lies like a man shot with arrows. They are blind to Mahmood Hussein Mattan and all his real manifestations: The tireless stoker, the poker shark, the elegant wanderer, the love-starved husband, the soft-hearted father.” How did you develop the complex character of Mahmood Mattan—his childhood in Somalia, his life at sea, his love for Laura and their three sons, all the scenes and memories?

I wanted the reader to be able to contrast my “fiction” with the fiction passed as fact by the law courts.

NM: By casting a wide net. I wanted to hear and read what a diverse group of people thought about Mahmood: from Laura who said “he was the best thing that ever happened to me” to the prison doctor who spends time interviewing Mahmood about his early life. I was also lucky enough to meet an elderly sailor who had been at sea with Mahmood for eight months.

JC: The sense of place is powerful in this novel. How did you recreate the neighborhoods of Cardiff—the docks of Tiger Bay, where sailors carry parrots or monkeys in makeshift jackets to sell of keep as souvenirs; Butetown, where Mahmood visits Berlin’s Milk Bar and settles at night in a boarding house; Adamsdown, where his wife Laura, their three sons, her parents and younger siblings live in a house hit by shrapnel from a German bomb during the blitz; Cardiff Prison, near Mahmood’s lodgings; the Law Courts?

NM: Imagination! And perspiration. I spent quite a lot of time in Cardiff and was helped by local people. I knocked on many doors to get at individuals who might have something useful for the novel. Old Cardiff newspapers were also a fantastic view into the social life of Cardiff in the 50s.

JC: Can you describe the process by which you researched the details of this legal case? What documents, records, archives were available?

NM: A huge amount, thankfully. At the National Archives in London the case file was open so I was able to read from the first interviews Mahmood had with police to the last minute appeals to spare his life. It was heavy reading the ways in which Mahmood’s life was stolen from him, especially as I knew how the story ended while he couldn’t.

JC: You include courtroom scenes, and testimony in one section of the novel. Are these from actual transcripts?

NM: Yes, they are verbatim extracts from the real court transcripts. They were so humorous, tense, chilling that they read as a work of fiction or a play. I wanted the reader to be able to contrast my “fiction” with the fiction passed as fact by the law courts.

JC: How were you able to reconstruct Mahmood’s jail time experience, especially his time in the “condemned suite” in Cardiff prison, where he is haunted by the nightmare of the jury trial that condemned him to death (“English is like barbed wire to him now, a lethal language that he needs to keep outta his mouth.,” he notes at one point). His musings on justice and injustice, life, death, his own mortality, are profound. How were you inspired by Ahmed Ismail Hussein—Hudeidi—who wrote about his detention in French Somaliland in 1964?

NM: Hudeidi, who sadly passed away last year, was born around the same time as Mahmood and spent quite a few years in prison because of his anti-colonial activism. His stories, his spirit, his love of language definitely suffuse this novel. Cardiff prison as well as Bristol prison kept records of all prisoners so I was able to piece together Mahmood’s time in jail through those documents.

JC: How painful was it to work with this material over the course of writing the novel?

NM: In hindsight, the collaborative and investigative aspects of this novel allowed me to hide from the very traumatizing elements of what happened to Mahmood but I do remember sobbing as I wrote a couple of passages towards the end of the novel. I wish I could have saved him or helped him in some way.

JC: What are you working on next? Will you be you coming to the US soon?

NM: I’m moving to New York City next spring to teach at NYU, which I’m excited about. I’m also hoping to write my fourth novel while I’m there, something very different to The Fortune Men.

__________________________________

The Fortune Men by Nadifa Mohamed is out now with Knopf.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.