A Star is Born: Tracing the Rise and Fall of a Jewish Immigrant Turned Realist Author

Catherine Rottenberg on the Storied Life and Overdue Revival of Anzia Yezierska

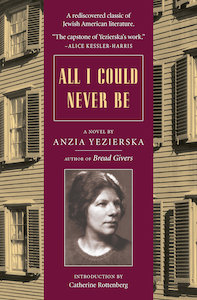

Anzia Yezierska’s literary texts have generated increasing scholarly interest over the past few decades. This is true not only within Jewish American studies, where students are very often required to read her work, but also more broadly within immigrant, women’s, and multi-ethnic studies. Yezierska’s best known novel, Bread Givers (1925) is now considered a modern classic—at least in the Jewish American literary tradition—and has become a cornerstone in numerous university and college courses. Yet, like so many women novelists of previous centuries, Yezierska’s canonical status is a phenomenon of the recent past.

Although the young Eastern European Jewish immigrant experienced a “meteoritic rise” to fame in the early 1920s, which catapulted her into the literary limelight and briefly to Hollywood, her popularity was short-lived in her own lifetime. Already by the Depression Era—a mere ten years after the publication of her well-received short stories—Yezierska’s gritty depictions of poor Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side had fallen out of favor. It would take approximately 40 years of obscurity and the feminist momentum of the 1970s before Yezierska and her works were rediscovered.

When Bread Givers was first reissued in 1975 by Persea Books, Alice Kessler-Harris noted in her introduction that few people had, at the time, even heard of the once-famous writer Anzia Yezierska. In the years that followed, however, Kessler-Harris’s pioneering research on the forgotten “sweatshop Cinderella” as well as her determination to republish Yezierska’s fiction would significantly change this cultural amnesia. The timing was right; there was a receptive audience for Yezierska’s vivid narratives about independent-minded, working-class immigrant women.

Bread Givers succeeded in a big way, welcomed by both the general reader and educators, and is still widely read. In addition, three collections of Yezierska’s short stories (Hungry Hearts, The Open Cage, and How I Found America) as well as two other novels have been successfully reprinted: Salome of the Tenements in 1995 and Arrogant Beggar in 1996. Today, it is no longer unusual to see one of her two (still) lesser known novels appear on university syllabi or reading-group lists, and there is currently a small but growing cadre of dedicated Yezierska scholars. Thus, in the second decade of the 21st century, Kessler-Harris’s early statement has become happily anachronistic.

Since the 1980s, and similar to other minority literatures in the United States, many previously “lost” Jewish American texts have been rediscovered. Yet, it seems fair to say that few if any early 20th-century Jewish American authors have elicited the amount or the kind of interest that Yezierska has. Unlike contemporaneous authors, such as Samuel Ornitz, Ludwig Lewisohn, or Sydney Nyburg, Yezierska’s fiction has appealed to a much wider and more diverse audience. This appeal has to do, in large part, with the forceful way her fiction continuously returns to a theme that still resonates strongly in the United States: the dilemma of being strong-willed, female, ambitious, and part of a minority group whose cultural norms and traditions clash with the dominant culture.

*

In her 1995 introduction to Salome of the Tenements, Gay Wilentz perceptively describes Yezierska as the author of semi-fictional autobiography and semi-autobiographical fiction. It could easily be claimed, for instance, that Yezierska often created her protagonists very much in her own image. By all accounts—and analogous to her fictional women characters—Yezierska had an extraordinary driving will and an intense, explosive, and impassioned personality. However, due to Yezierska’s tendency to “mythologize” her own personal history, it has taken scholars many years to sift fact from fiction as they have attempted to piece together an accurate portrayal of the author’s life.

Today we know that Anzia Yezierska was born in the Russian-Polish village of Plostk sometime in the early 1880s. Her mother, father, three brothers, and three sisters (two more brothers were born after the family’s emigration) arrived at Castle Garden around 1890; she was between eight and ten years old. And like so many Jewish immigrants who arrived from Eastern Europe during these years, the family settled in the already vastly overcrowded Lower East Side.

Anzia’s father was a Hebrew scholar who continued to devote his time to religious study in the New World; this meant that the other members were responsible for supporting the family economically. Too young to work in the sweatshops, Anzia was initially sent to the public school. Her formal schooling did not last long, though, and she was soon forced to quit school and enter the workforce in various low-paid jobs: as a servant, a scrub woman, a laundress, and a factory worker. But ever eager to learn, Anzia diligently attended night school, even after working ten-hour shifts.

Like so many women novelists of previous centuries, Yezierska’s canonical status is a phenomenon of the recent past.

In her late teens, Anzia moved into the Clara de Hirsch Home for working girls in order to escape her family with whom she was constantly at odds. She soon chafed under the rigidity of the settlement house as well, for she was not one who could live long according the dictates of others. Anzia was, as her daughter Louise would later describe her, “a rebel against every established order.” Yet Anzia was also apparently armed with an impressive ability to persuade people to do her bidding, and she eventually convinced a few of the wealthy patrons of the settlement house to cover her tuition so that she could attend Columbia University. In 1904, after four years of study, Anzia earned a degree in domestic science from Columbia University Teacher’s College and subsequently worked intermittently as a teacher.

But Anzia did not take to teaching either, particularly the teaching of domestic science, and she toyed with the idea of acting, briefly attending the American Academy of Dramatic Arts on scholarship. During this period she also tried living at the socialist Rand School, and, in 1910, when already in her late twenties, experimented with matrimony. Her first marriage lasted less than a year, and her second marriage took place soon after the annulment of the first. As Katherine Stubbs recounts, Anzia chose to have a religious ceremony the second time around so that the marriage would not be legally binding. Before separating from her second husband, Anzia gave birth to her daughter, Louise Levitas, in 1912. Louise was, however, to spend most of her childhood years living with her father and grandmother.

In her biography of her mother, Louise reconstructs these years of indecision—between married life and being single and between different career options—narrating how Anzia found inspiration in and from her older sister, Annie, who told vivid stories about her life of poverty in the Lower East Side ghetto. Louise suggests that it was “Annie’s mimicking of her children and neighbors” that first motivated her mother to write short stories. Disillusioned with teaching and estranged from her second husband, Anzia decided to become a writer.

It was also during this period that Anzia first met John Dewey, the well-known and respected professor of philosophy at Columbia University. This encounter in 1917, when Anzia was around 37 years old, would change the course of her life. Anzia initially approached Dewey—bursting into his office unannounced, as the legend goes—in order to ask for help in gaining a better teaching position. Given her larger-than-life personality, it seems that Anzia’s determination, passion, and unconventionality captivated Dewey, so much so that he eventually presented her with her first typewriter and introduced her short stories to magazine editors whom he knew. He also encouraged her to audit his graduate seminar in social and political philosophy.

As the relationship developed, Dewey ensured that Anzia was hired as a translator for a research project—very like the one described in All I Could Never Be—whose goal was to investigate the Polish community in Philadelphia. The wages were generous enough to enable Anzia to spend most of her time writing. However, this project also proved to be the beginning of the end of Anzia’s relationship with Dewey, whose short-lived passion for this Eastern European woman has been immortalized in the poetry he wrote to her. While the real-life relationship ended abruptly, likely as a result of Yezierska’s refusing Dewey’s sexual overtures, Dewey had already left a profound and lasting mark on Anzia and on her writing. Many scholars have noted that Dewey-like figures constantly appear in various guises throughout Anzia’s fiction.

Many scholars have noted that Dewey-like figures constantly appear in various guises throughout Anzia’s fiction.

Perhaps ironically, it was only after this intense relationship fell apart that Anzia’s career as a writer finally took off. Her first story had been published in 1915, and from 1915–1919 there was a steady trickle of stories, one of which—“The Fat of the Land”—was chosen by editor Edward J. O’Brian as the best short story of 1919. Less than a year later, Houghton Mifflin published a collection of her stories under the title Hungry Hearts. Success bred success at this stage; her stories sold, and not long afterward, the Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn paid her ten thousand dollars for the film rights to her book. And so Anzia left for Hollywood; she was close to 40 years old.

But Anzia, being Anzia, was also unable to accommodate herself to Hollywood. Katherine Stubbs writes that the fierce commercialism of the motion picture industry shocked her and she objected to the way Goldwyn Pictures altered her novel’s plot for commercial considerations. By all accounts, Anzia developed writer’s block and felt stifled by the frantic competition and the whirlwind race toward the spotlight. She returned to New York and continued to write. But the times were changing.

Anzia published four more books in the next decade: Salome of the Tenements (1922, which was also made into a movie); the short-story collection Children of Loneliness (1923), Bread Givers (1925), and Arrogant Beggar (1927). While Salome met with mixed reviews, Bread Givers was admired “as a colorful, suspenseful narrative of family tensions in the ghetto.” The positive reviews of her second novel revived Anzia’s reputation for a short time, but when her third novel appeared in 1927, the reviews were not only lukewarm but were also few and far between. The sales of her fourth novel, All I Could Never Be, published during the Depression years, were paltry. As her daughter tells it: “The fad for Anzia Yezierska had apparently passed.” Thus, by the late 1920s Anzia’s literary fame had already ebbed.

Eighteen years of “silence” followed—years in which Anzia continued writing but could not get published. In the interim she worked various jobs, among them a job on the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration Writers Project. She produced and published one final full-length text, Red Ribbon on a White Horse, in 1950. Although she received the best reviews of her career for this semi-fictional autobiography, the book “died at birth.” From the 1950s until her death in 1970, Yezierska never stopped writing: she wrote review essays for the New York Times Book Review and short stories about old age.

Anzia Yezierska died in relative obscurity. She did not live to see the latest revival of her literary fame—a revival that, unlike the previous ones, appears set to last.

__________________________________

From All I Could Never Be. Used with the permission of the publisher, Persea Books. Introduction copyright © 2016, 2020 by Catherine Rottenberg.

Catherine Rottenberg

Dr. Catherine Rottenberg currently teaches American literature and gender studies in the Department of American and Canadian Studies at the University of Notthingham, England. She was born and grew up in New York City, earned her B.A. in Jewish Studies at Brown University and both her M.A. and Ph.D. in English Literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She has also been a fellow and/or visiting scholar at the University of California (Berkeley), the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), and at the Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton University. She lives in England.