A springtime field guide to the iconic flora of children’s literature.

Spring has officially sprung! The flowers will come in waves. First the daffodils, crocuses, and snowdrops. Then the tulips bloom loudly, followed by the zinnias and the lavender. And the roses will carry us till fall. But the greenery we can enjoy now—the ones we can return to even when winter has sunk its teeth in again—can be found in the pages of our favorite children’s books.

*

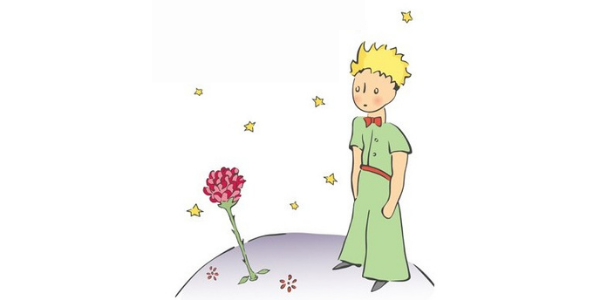

The Rose in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince

Origin: Little Prince’s planet, borne from a strange seed.

Characteristics: Red/pink in color. A little vain in personality.

Field Notes: The Little Prince obviously follows the eponymous petit prince as he travels from planet to planet, ruminating on loneliness and love. But another majority player in this is the rose. A classic beauty. It’s said that the relationship between the Little Prince and the rose is supposed to mirror the one between Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and his wife. Not sure how I’d feel about this as his beloved (see: characteristics). Still, she inspires his journey home. Ultimately, though, the rose is a symbol of love, and a reminder of the beauty that springs from caring for other people.

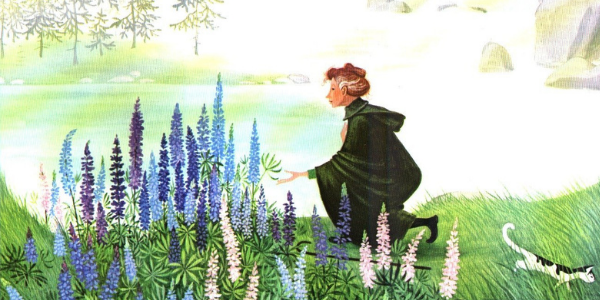

Lupines in Barbara Cooney’s Miss Rumphius

Origin: Western United States, but was introduced to Maine as a landscaping plant (potentially by Miss Rumphius herself; the story is loosely based on the real Hilda Edwards, who is credited for bringing this somewhat invasive species to the Northeast).

Characteristics: They bloom in a myriad of attractive colors: blues, pinks, and purples mostly. They can grow up to 3 feet tall.

Field Notes: When she is a little girl, Miss Rumphius promises her grandfather that she contribute to the beauty of the world and help make it a better place. She spends her whole life traveling the world, making new friends, having a litany of exciting adventures. (And she does it as a cool, single woman, which was definitely not something we saw a lot of in children’s books of the 1980s.) One day, she hurts her back and ends up in a small, seaside town. As she lays there in bed, she thinks about her promise to her grandfather. With the help of the wind, she plants the seeds for lupines—hundreds and hundreds of them to hug the hills of the town. (A quick Google search tells me that the lupine symbolizes imagination. It also tells me that certain strains of lupines are sometimes poisonous to animals, which gives this stunning image a slightly darker hue in my mind.) But anyway, the residents cherish the flowers. It’s a gorgeous illustration of the way our small deeds can leave the world more beautiful than when we found it.

Blueberry Bushes in Robert McCloskey’s Blueberries for Sal

Origin: Blueberries are native to North America and thrive in Maine, where this story takes place, at Blueberry Hill.

Characteristics: The blueberry bush has ovular leaves and stems that go from green/yellow to reddish in the winter. Depending on the variety, some blueberry bushes can grow up to 12 feet tall, while others top off at around 2-4 feet. They gift us blueberries through the summer.

Field Notes: Blueberries for Sal is mostly about the love between a mother and her child. Both bear mother and human mother are teaching their offspring the importance of storing up for winter. I think there’s something to be said about the fortifying effects of a mother’s love and the antioxidant properties of blueberries.

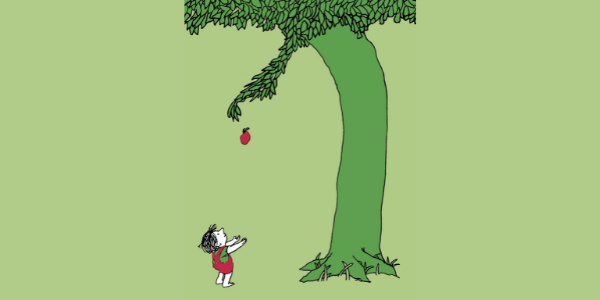

The Giving Tree in Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree

Origin: Apple trees originated in Central Asia and were brought to North America by European colonists; for the purposes of this story, though, this tree originates in some spoiled child’s backyard.

Characteristics: Apple trees can grow up to 30 feet tall, bearing fruit in late summer through the fall. Generous.

Field Notes: The titular Giving Tree is a selfless being, offering all the parts of herself to this greedy little boy who grows into a greedy little man. It’s been said that she represents motherhood and also the thoughtless decimation of our planet. A gentle reminder that Ryan Gosling has this tree tattooed onto his body.

Truffula Trees in Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax

Origin: The Truffula Tree Forest, later known as Thneedvile

Characteristics: Yellow-and-black-striped bark with tufts, typically in warm tones (reds, oranges, yellows, pinks, purples). They supposedly emit a heavenly scent of fresh butterfly milk.

Field Notes: Of course the Truffula Trees were going to make an appearance! They represent a simpler, more idyllic time. They are at the heart of Dr. Seuss’ climate change book for kids. Look at how majestic and fluffy they are! Don’t their colors make you smile? Wouldn’t you like to touch one? That’s what the Once-ler is thinking, too. He’s thinking people would pay a pretty penny for a thneed made of such soft material. (Capitalism!) He’s chopping the whole forest down, which of course, has disastrous effects on the whole ecosystem. Look outside your window: it’s happening in real-time. Unless.

Wild Flowers in Shel Silverstein’s The Missing Piece Meets the Big O

Origin: Unknown.

Characteristics: The definition of a wild flower is one that is not intentionally planted. They come in all shapes and colors and sizes. They symbolize joy. (To that, I would add resilience.)

Field Notes: I guess the flowers aren’t that important in this book, but I will use any excuse to write about Shel Silverstein’s underrated masterpiece, The Missing Piece Meets the Big O, in which the missing piece sits in a field, waiting for the thing it can complete—its soulmate. It encounters pieces that have too many missing parts, and pieces that just aren’t the right fit. Many pieces pass by and take no notice of the poor missing piece. On one of the saddest and most relatable pages(pictured here), the missing piece dons flowers “to make itself more attractive.” Spoiler alert: in the end, the missing piece realizes it can be whole all on its own. It rolls and rolls, and we see the flowers in the field finally in full bloom.

Katie Yee

Katie Yee is a Brooklyn-based writer.