A Single Ray of Light: On Ray Bradbury’s “All Summer in a Day” and Living in the Shadow of Long COVID

Jessie Chaffee: “For a moment, I am the girl, her existence of gray monotony broken by a sliver of sunlight while others revel in the day’s abundance.”

“My first well Day—since many ill—

I asked to go abroad,

And take the Sunshine in my hands,

And see the things in Pod—”

—Emily Dickinson, 574

*Article continues after advertisement

When I was a child, I spent many long afternoons at Jefferson Market Library in Greenwich Village. It seemed more castle than library, with its red brick walls, gothic windows, and soaring clock tower. In fact, it was constructed in the late nineteenth century as a courthouse, along with an adjoining prison, now gone. The Children’s Room, where I spent my earliest years, had been a police court, and in the brick-arched basement, where I scrolled microfiche in middle school, prisoners once awaited sentencing, most of them women, many of them on the fringes of society.

In 1929, the prison portion was torn down and replaced with the New York Women’s House of Detention, an art deco structure that loomed high over the courthouse. The House of D, as it was known, became a site of protest and queer activism, and detainees included revolutionaries like Angela Davis. While the courthouse was abandoned and then refurbished as a library in the ’60s, the prison kept its original purpose until it was shuttered in 1971. By 1979, the year I was born, the prison had been demolished, lush gardens planted in its place.

But as a child in the ’80s, I didn’t yet know this history, recent as it was, and I was oblivious to its ghosts. To me, the library was a castle, and there was always a bit of magic in ascending the spiral staircase to its upper floors, my steps echoing off the cool stone. Two decades later, my husband would begin a birthday scavenger hunt for me there, the first clue tucked into a volume of Proust. Three decades later, I would bring my own son to the library to look for graphic novels and comics—hero stories—and he would tear up those stairs ahead of me, feeling the magic of the place as he enacted the tales.

I subsist on teaspoons of life—a dinner with a friend must sustain me for weeks; a paragraph of writing must sustain me for days.

It was during one of my own childhood afternoons in the “castle” that the librarian showed a short film that would stay with me into adulthood, an adaptation of the Ray Bradbury story “All Summer in a Day.” I was maybe eight. I didn’t know who Ray Bradbury was, and I would subsequently forget the film’s title, would have no way of accessing it again until many years later when I stumbled, by chance, upon the story. And then the memory would surface, uniting the words with the images that had haunted me, like one of those old Viewfinders—you pull a lever and the reel moves, progressing statically through the narrative:

Children hurry through a concrete courtyard on a gloomy Venus, where it always rains.

Cut to them indoors in tinted goggles, turning one way, then another, in unison, preparing for the arrival of the sun, which comes once every seven years, and only for one hour. The adults are afraid, and the children, too, except for one girl who used to live on Earth, who, having known the sun, knows there is nothing to fear.

Cut to the closet in which her peers lock this girl, perhaps because of her knowledge, her lack of fear.

Cut to the sun’s arrival, sudden and complete.

Cut to the children, bathed in its beauty. They shake off the adults’ warnings, tear off protective gear, feel the warmth on their skin, run carefree through the grass, chase and tumble, take in the abundance of life. Forget the gray, forget the girl.

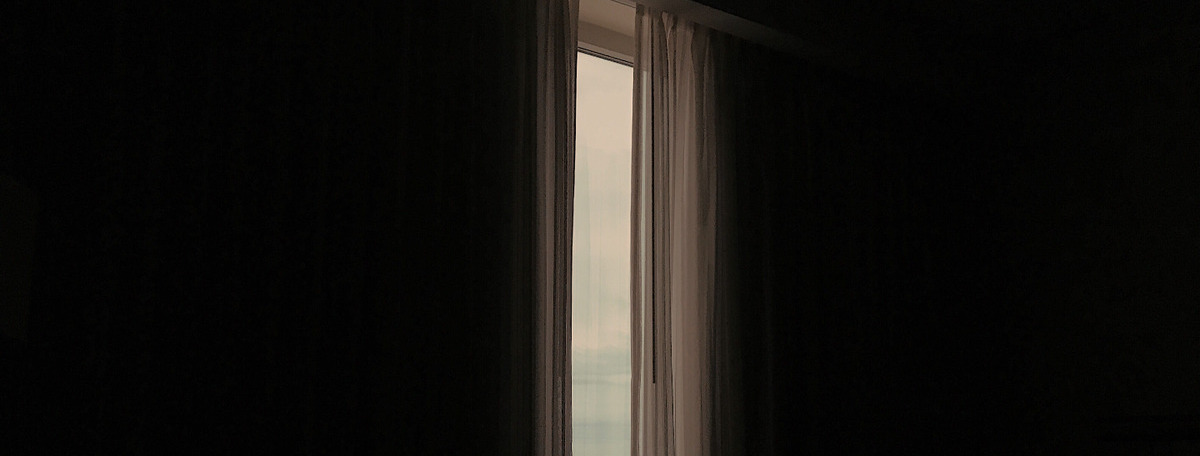

Cut to the forgotten girl. In her cell, a sliver of light enters. She runs her fingers through it. She smiles.

Cut to the first raindrop as clouds crowd back in. Then the second, then a handful, then too many to count.

Cut to the children, who remember the gray, remember the girl.

Cut to their arrival at the closet door, armed with the flowers they’d picked with abandon. Cut to their wordless release of the girl, who rejects the blossoms.

Cut to the girl as she walks out into the courtyard, everything gray again. She squints up into the rain, searching for the sun.

Cut to the children gathered around her. First one, then another, then all fill her arms with flowers, until she drops her gaze, rejoins the crowd.

Fin.

*

It must have been winter because it was almost dark when my mother picked me up from the library at five o’clock. Outside, the evening was as gray as the film, and I carried with me the grief of the story. The girl’s missed hour of sun made worse by the knowledge of what was she was missing. The impossibility of her getting that hour back, the impossibility of the children righting their wrong. That pitiful sliver of light. That pitiful girl who, even in her grief, smiled as it hit her fingers.

*

Three-and-a-half decades later, I look out the window of my apartment in the West Village, where I still live. I rarely leave home these days. In 2022, following a COVID infection, I developed what would eventually be diagnosed as long COVID, a poorly understood and debilitating complex chronic illness for which there is, currently, no cure. Overnight, my body, my sense of self, and, most distressingly, my relationship with my three-year-old son were upended. Once active and fully present in my son’s life, my illness means that I am mostly homebound, trapped in what feels like a stranger’s body, and sequestered from the world.

Long COVID looks slightly different for each person. For me, it includes dysautonomia, a condition in which the autonomic nervous system, one of the most primal parts of us—responsible for everything from breathing to fleeing danger—is malfunctioning. My long COVID has also brought cognitive dysfunction and cardiovascular issues. Most debilitating, however, is the chronic fatigue. If I do too much—and “too much” can mean anything from playing with my son for a few minutes too long to walking an extra block—I’ll have a fatigue crash, and when I crash, I’m unable to do anything. And, so, my perch at this window is semi-permanent.

It’s evening and the sun is glaring as it sets into the Hudson—we’re knee-deep in October, and it disappears earlier each day. I cup my hands over my eyes, squint though the glass at the world I’ve kept away from while my body has revolted, heartrate bouncing up uncontrollably, fatigue weighing me down. I look for glimmers of what I’ve missed.

And then there they are, my husband and son, about to cross West Street. My son is on my husband’s shoulders and, lit from behind, they become a double-headed creature. Today they drove an hour out to New Jersey to a farm. Saw friends, picked pumpkins, rode in a wagon, celebrated the fall. My husband sent me photos throughout. My son was jubilant in every one.

I don’t know if they can see me, light glinting off the glass, but then they look up, and I can see my son’s painted face. My husband points and they both wave, this double-headed creature around whom I orbit.

I feel in this glimpse the day without me, feel the cell that is my body. And, in a rush, I remember the darkened library, the dull planet, the girl in the closet, the sunlight filtering in. For a moment, I am the girl, her existence of gray monotony broken by a sliver of sunlight while others revel in the day’s abundance.

And then I feel the full weight of this missed day, how it sits upon all the other missings of these years with long COVID—Christmas with family, nights out with my husband, the beach with my son, my best friend’s art opening, walks to school, aimless strolls through the city, plays, parties, concerts, time with friends, writing, reading, traveling, imagining. All the things I did when I wasn’t trapped in this body.

The birthday scavenger hunt my husband set up for me a decade ago—we zig-zagged through the Village, up the stairs of the library’s tower to the clue in the book that sent us west to our local bookstore, then north to a small clothing shop, then south and west to our beloved bar, the Spotted Pig, now gone, where a glass of wine and deviled eggs sat ready, and finally home, four stories up, where friends were waiting to surprise me. How many steps had I taken that day, unconsciously, freely? In those years, I was still teaching, and I would bike along the Hudson, one hundred blocks to the school on the Upper West Side, where I taught all day before coasting home in the golden evening light.

In May of 2019, on the day our son was born, my husband and I walked the streets of our neighborhood, trying to move labor along. It was early morning, Saturday, and the Village was quiet. I was thirty hours in, and still I walked block after block, pausing only for contractions, gripping scaffolding or stoop railings or my own knees as I waited for them to pass. We stopped at the “Good Night Moon house,” a gated, crooked, white structure, trimmed in blue, where Margaret Wise Brown had once lived. Later, I’d walk the same streets with our son, now out in the world—uptown, downtown, crosstown.

For three years we strolled to classes and parks, to preschool and gatherings with friends, memories surfacing as we kicked up the dust of my own childhood at Jefferson Market Library, Bleecker Playground, Three Lives Bookstore, and McNulty’s Tea & Coffee, where I once sat happily on the stacked burlap bags, inhaling the sweet, thick aroma. I’d sometimes take us out of our way to pass the Good Night Moon house—“We were here,” I’d tell my son as we peered through the gate, “Right here on the morning you were born.”

In the context of the decades I may spend chronically ill, I am in my infancy. The question of who I will become remains.

A few months before I became ill, we celebrated Father’s Day with a walk all the way down to South Street Seaport, sometimes ambling, sometimes running to keep up with our son, stopping for food and then at a playground where we chased him from structure to structure—I climbed high up into one to help when he found himself suddenly frightened, and guided him back down. At the Seaport, we ducked inside an art installation on the river—a stained-glass house that painted us all in color. We took the subway back to our neighborhood, our son spinning around the pole as I once did. We had an early dinner outdoors on Christopher Street, and my husband and I finally rested as our son pantomimed with a kind couple dining indoors, their laughter reverberating through the glass. We were out all day long, arrived home as it was growing dark, sunburned and weary—the good kind of weary—and happy.

Now I subsist on teaspoons of life—a dinner with a friend must sustain me for weeks; a paragraph of writing must sustain me for days. If I want to take my son to the Good Night Moon house, a few blocks away, we’ll go by cab, there and back, and it may be the only break in a long stretch of time spent indoors. An hour of sun for every seven years—or an hour of a sliver of sun. I go to a book launch but miss the after-celebration. I go to Thanksgiving but spend much of it locked away resting, then days after recovering. I choose x over y, later y over z. I feel these choices now, feel the omissions and how they accumulate into something like a full life, another life. It hollows me out.

Still, most of the time I’m not grieving, not bitter. I’m just living within my limitations. I’m just living. Tonight, I’m grateful for the glimpse of the day in the waving figures of my husband and son. Because in the glimpse I see and am seen, and I’m missed too, even as I know that most of the world has rolled on, oblivious to those of us for whom time has stopped. I’m grateful because many days I don’t get this glimpse. Many days feel like standing alone in the gray, looking up for the light that is already disappearing.

*

When I re-read the Ray Bradbury story, I find it’s different from the film. In the original story, we’re never in the cell with the girl—we don’t know what she saw, how she felt during that endless hour. And the story ends with the children, arms empty of flowers, beginning to open the door, behind which lies only silence. We don’t see the girl emerge, don’t see her cross the courtyard, don’t see her look up, don’t see her embraced by the group.

The film was made for educational purposes, to be shown in libraries like mine, to teach kids about the dangers of bullying, I imagine. And the added scenes? In some ways, they let the bullies off the hook, and the viewer too. They’re a reprieve from the loss. The shaft of sun, the armload of blossoms, even the smudge of light through the clouds—these glimpses are a balm for her and for us, who do not have to imagine her silent agony, who do not have to witness her missing.

*

That would be where my relationship with that long-ago afternoon in the library ends. Except that I come across an article about its sister building, the Women’s House of Detention, and, all these years later, the narrative is again recast.

I don’t know why I wasn’t aware of the prison’s existence earlier. Growing up in the Village—on Christopher Street proper for the first seven years of my life, two blocks from Stonewall—I knew something about LGBTQ culture and history. But I didn’t know about the House of D, where, for decades, queer and gender-nonconforming people—many of them people of color—were held, often because they were queer or gender nonconforming.

I knew about the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, but not that the detainees participated from within the walls of the prison, chanting, shouting, throwing burning belongings out those art deco windows. I knew that every June since Stonewall, the Village has exploded with Pride, but not that the House of D had also drawn crowds—family, friends, and lovers arrived to converse with those inside, whose hands and faces appeared at the prison’s windows, their voices carrying to Greenwich Avenue below.

The dark prison abutting Jefferson Market Library was a site of isolation, but it was also a site of connection—and intense resistance. In her autobiography, Angela Davis describes the abuse the inmates endured, and the tranquilizers they were given at meals to quash any rebuttal—despite this, they fought back. Another inmate, author and activist Andrea Dworkin, testified about the assault she experienced at the House of D. And the friends and families and lovers along Greenwich Avenue were joined by demonstrators, who protested the abuse, who bore witness to those who were missing, who may have been trapped in that tower, but were not invisible. The detainees and their community did not allow the world to forget them. Eventually, under the mounting pressure, the prison was closed.

*

I think back to that gray evening in the library, and I wonder—what if instead of being projected forward to life on Venus, I’d been projected back to the history of that square block, to a different group of people—real people—who were shut away from the world? What ghosts might I have carried with me, might I be living with now? And how might they shape the way I think about this moment, and my role in it—as someone who is on the fringes of ableist society, yes, but who, as a straight cis white woman, has privileged access in so many other ways?

Because there are people resisting erasure. There are people challenging the “post-pandemic” story, in which COVID is a historical blip rather than an ongoing and devastating narrative. One morning, a year-and-a-half into my illness, I watch the U.S. Senate Committee Hearing on Long COVID, a meeting that is only happening because of the advocacy of groups like the Patient-Led Research Collaborative and Long COVID Moonshot. Bernie Sanders introduces the meeting, and I weep as he states the simplest truths:

“Long COVID is a very serious illness that can have devastating consequences for those who contract it….Long COVID can include more than two hundred symptoms, including serious cognitive impairment and severe cardiovascular and neurological problems….Far too many patients with long COVID have struggled to get their symptoms taken seriously.”

None of this new to me, and yet hearing it acknowledged feels groundbreaking. Then the panelists give testimony. Rachel Beale, a mother of three, says, “My kids have grown accustomed to me being sick….Full recovery seems out of reach for me. I’ve been sick for almost three years.” Her appearance in person at the hearing is a physical sacrifice—it will trigger a days-long fatigue crash, she predicts. Nicole Heim, whose teenaged daughter has long COVID, testifies, “Long COVID stripped away my daughter’s life as she knew it.”

Angela Vázquez, former president of Body Politic, a grassroots organization founded by Fiona Lowenstein that connected and advocated for long COVID patients, shares her prolonged journey to diagnosis—one impeded by disbelief and gaslighting, and made worse by the inequitable treatment she received as a woman of color. Then she says something that both resonates with and terrifies me: “We are living through what is likely to be the largest mass disabling event in modern history.”

*

Since growing ill, I’ve become a different person—the omissions change me. But in the context of the decades I may spend chronically ill, I am in my infancy. The question of who I will become remains. I’ve felt isolated in this experience, but I am not alone. I’ve felt invisible, but there are activists like the three women testifying—and all the advocates beside them—who, despite the prisons of their bodies, have found a way to make their voices heard, to ensure that people are noticing the missing.

This activism will only become more vital. A year after the U.S. Senate Committee Hearing on Long COVID, Donald Trump will take office. He and his administration will do everything in their power to erase anyone who is not cis, white, straight, wealthy, and able-bodied. They will eliminate the Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. They will order the Department of Health and Human Services (HSS) to terminate the hard-won Advisory Committee on Long COVID, a group that included scientists, doctors, and patient advocates. They will cancel hundreds of millions of dollars in medical research grants—in particular, research related to vaccine hesitancy, issues affecting LGBTQ communities, and HIV prevention. And they will pull back 11.4 billion dollars in COVID response funding. When asked about this last item, the HSS’s Communications Director will say, “The COVID-19 pandemic is over, and HHS will no longer waste billions of taxpayer dollars responding to a non-existent pandemic that Americans moved on from years ago.”

A “non-existent” pandemic that, at the time of his statement, will have killed 1.2 million people in the United States, 7.1 million worldwide, felled by a virus that will still be circulating and mutating. A “non-existent pandemic” that will have left, conservatively, twenty million people in the U.S. and four hundred million people globally permanently ill, reduced to teaspoons of life, with no cure in sight. For the millions dead, and their loved ones, for the millions disabled, and their loved ones, there will be no moving on. And resisting erasure will become both more difficult and more necessary.

*

I plan to rewatch “All Summer in a Day.” On my own, not with my son—I won’t saddle him with that particular grief. But on a future library trip, I will tell him the story of the Women’s House of Detention, of the protests of the past that reverberate in the protests of our present. And I’ll speak with him about long COVID advocacy—so that he knows there is more to this illness than my long days spent at home without him. What is the “more”? What will I tell him? What do I tell myself? That being trapped doesn’t require passivity. That we can be grateful for a sliver of light and still fight for the fullness of the day. That there are many ways of looking, and of shouting, out windows.

Jessie Chaffee

Jessie Chaffee's debut novel, Florence in Ecstasy, was a San Francisco Chronicle Best Book of 2017 and was translated into six languages. She completed the novel with the support of a Fulbright Grant to Italy. Her work has appeared in The Rumpus, Slice Magazine, and The Florentine, among other places. She lives with her family in New York City.