A Scientific Explanation for Your Urge to Sniff Old Books

Jude Stewart Breaks Down the Chemical Reactions Behind Olfactory Bibliomania

Inside its dry and musty hull, the smell of old books contains great distances. You sense time travel, of course, but also the soaring aeronautics of ideas. Sometimes a great book sticks the landing, very often they don’t. And sometimes books fail to jump high enough.

In smelling old books, you can smell actual geographic distances, too. Imagine all the cardboard boxes necessary to crate up a roomful of books, the slow trundle of cargo to a new destination, the books aging along with their owner from move to move. Readers who find this smell intoxicating are ruefully aware of how insane, how flatly contradictory of convenience, loving this smell can be.

From an old book filters up a whiff of dissolution and conjuring. Ghosts, like smells, are composed of particles, a levitating cloud forming a slightly denser shape than the surrounding air. The disembodied words of writers, whether dead or otherwise absent, find body in these volumes.

The litany of things book-smell resembles suggests elements of peaceful civilization: Well-rubbed wooden furniture. Leather bookmarks. Just-opened tobacco tins. Toasted almonds mixed with vanilla. Tea. Pressed flowers. Radiator heating pinging on. Candles and spent matches. Undisturbed dust, with its suggestion of perfect stillness and the happy dilation of hours spent reading.

This is an intimate smell that’s not necessarily miniature. You can smell a single old book, riffle through its pages rapidly and let your nose bask in the scented breeze. But just as often you encounter this smell as a solid wall in a used bookstore or library. Writ large like this, old books smell like a constructed forest: ancient and druidical, exhaling to make their own atmosphere, a forgotten primordial home.

The smell of old books stems from their slow chemical decomposition. Books are largely paper, and paper is largely plants. But the materials from which books are made have shifted over the centuries—and those shifts, in turn, have influenced how different generations of books smell. Before 1845, paper in books was manufactured from cotton and linen rags. These plants contain a high percentage of cellulose, a kind of polymer that gives plants stiffness. Cellulose is largely stable in paper over the years unlike its cousin lignin, another plant polymer frequently present in paper.

The 1840s saw the invention of a process to manufacture paper from wood pulp fibers. This produced paper that was less durable than paper made of cotton or linen, but more plentiful and therefore cheaper. Wood-pulp paper has heavy lignin content unless you extract the lignin deliberately finer-quality papers tend to contain less lignin than newspaper. In trees, lignin binds cellulose fibers together and gives wood its extra backbone—which would seem like a desirable quality for bookbinding. What early bookmakers didn’t realize was a lesson only learned over time: lignin is strong during a plant’s life, but it’s prone to wild and destructive decay after death. As lignin oxidizes, it breaks down into acids that eat away at paper’s cellulose and turn the pages yellow. All of these processes of decay throw off volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, that impart a distinctive smell to aging books. Around 1970 acid-free paper was introduced to bookmaking, removing most of that calamitous lignin so that modern books degrade much more slowly. Even without lignin, however, cellulose eventually decays and releases scents.

The smell of books fuses with the smell of rooms, and the readers who habitually occupy them. Books’ fragrance reflects the environment they’ve long resided in: if that space is particularly humid, smoke-filled, sunny, or not climate-controlled. If those rooms happen to be iconic, like the Wren Library at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, then the smell itself can be considered a tangible part of a site’s heritage. Analyzing the VOCs wafting from books, researchers can discern what materials the book was made of, pinpoint its age, and whether any disastrous processes are at work that preservationists might want to halt or reverse.

Brand-new books also have a distinct smell, if a less singular one. Modern paper manufacturing uses chemicals like sodium hydroxide (or “caustic soda”) to boost pH levels and swell up the pulp fibers. Those fibers can also be bleached in hydrogen peroxide, then mixed with copious amounts of water laced with alkyl ketene dimer, a sizing agent that makes the paper more water-resistant. These chemicals decompose at various rates, throwing off smells in turn. The various inks and adhesives used to bind books together do the same. As soon as a book or any object is made, it starts to unmake itself—a chemical process we can smell.

_____________________________________________________________________

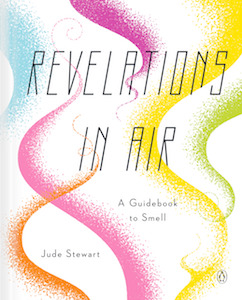

From REVELATIONS IN AIR by Jude Stewart, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Jude Stewart.

Jude Stewart

Jude Stewart is author of three books, most recently Revelations in Air: A Guidebook to Smell (Penguin Books, 2021). She has written about design, science and culture for The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, The Paris Review, Quartz, The Believer, Fast Company and many other publications.