A Saga in Miniature: On Halldór Laxness’s A Parish Chronicle

Salvatore Scibona Explores the Literary Legacy of Iceland's Nobel Laureate

Einginn fær mig ofan í jörð

áður en ég er dauður.Article continues after advertisement(No one puts me in the ground

before I’m dead.)–Þorsteinn Erlingsson

*

In October 1969, Halldór Laxness was in Rome doing what came naturally to him whenever he could get to his favorite city: shopping for women’s shoes. A clotheshorse even in his hard-up and ardently communist early days, he was at sixty-seven flush, and could now buy what he liked. But the state of European fashion depressed him. Nothing suited his taste. Certainly not the shoes, which he found “deliberately ugly.”

About the fate of his work he had lately been in outright despair. At twenty-nine he had promised in a letter, “I shall become a great writer in the eyes of the world or die!” But in a recent essay he claimed never to have had any real success in his home country, where he believed he was “now rightly forgotten by those few friends who once hoped that I would achieve such a thing.” More than once he had sworn off writing novels for good.

Laxness was the heir not only to the language and setting of the sagas but to their humanity, their outrageous understatement and charm.

If he hadn’t had such grandiose ambition, would he have been so prone to grandiose disappointment? Or so immune to evidence that in the eyes of the world he had done fairly well? After all, he had won the Nobel Prize fourteen years before and was probably the most famous Icelander since Snorri Sturluson, the thirteenth-century historian and poet and one of the few medieval Icelandic writers whose names we know. By anyone else’s estimation, Laxness’s books had sold robustly in Iceland for years.

Nonetheless, it was true that the international readership Laxness had once craved hadn’t quite come to him. In the United States, for example, nearly all his dozens of books were out of print or had never been translated. The ego that had made it possible for him to write and publish his first novel at seventeen was the same undying tormentor that made it excruciating to accept anything from the world short of continuous acclaim.

By the time he arrived in Rome that October, fresh off a publicity junket in Denmark, he had lived about twenty years longer than his father had. He might reasonably have assumed he was nearing the end of his productive life. He didn’t know that he still had six more books to go, or that the many readers he had once hoped for would begin to find his work, especially in the English-speaking world, only after he would die twenty-eight years later in an Icelandic nursing home in 1998.

Since then, the new American edition of his masterpiece Independent People has gone into forty-four printings. Through reissues and new translations by Philip Roughton of major novels including Iceland’s Bell (2003), Wayward Heroes (2016), and Salka Valka (2022), the big, ambitious, often political or historical, but always wickedly funny novels of Laxness’s mid-career have become available to English-language readers. For us, it’s as though this man has been publishing new work for ninety years, since Salka Valka was first translated from its Danish version and published in London in 1936.

The shoes were for his wife and daughters back home in Iceland. (He often stocked their wardrobes when he traveled.) His shopping companion was Fru Dinesen, an intrepid spirit right out of the sagas, who had left the Danish farm where she was raised; gone to England to work as a housekeeper; moved to Italy; married an Italian who couldn’t support her; been widowed at forty-four; and by a bewildering mixture of nerve and luck (and despite the interference of two world wars) gone on to make herself a prominent Italian hotel proprietor, all while raising six children and publishing four memoirs. Five years earlier, the king of Denmark had knighted her. Laxness had been visiting her hotels in Rome since the thirties. She was ninety-seven years old.

One wonders if Laxness considered at least her a success, or any of the dozens of brilliantly drawn Icelanders in his novels who are born with nothing and die with less but in the meantime live with the self-possession and spiritual vision of saga heroes or saints.

In any case, the other thing that came naturally to Laxness in Rome was to write a novel, which he could do there in sun-drenched rooms with the windows open. He evidently could not help but write there. His biographer, Halldór Guðmundsson, states that Rome always worked on him like a drug. The torture of his egoism about writing seems to have made the act of writing all the more necessary; it freed him from himself. When a novel got going, Laxness once wrote his second wife, it “lives in me a like a separate world.”

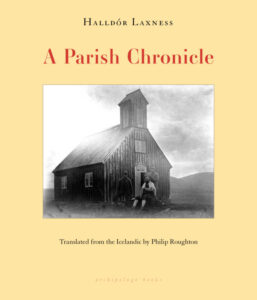

The world that came alive in him that October was A Parish Chronicle, a short novel he had drafted six years before and set aside. It begins around the tenth century and sprints like a racehorse with light-footed gusto into what was the present day, all while maintaining the canny facade that it is nothing more than a vignette of sleepy parochial history, a sketch on the back of a brochure. Perhaps inspired by Dinesen’s age and resilience or by the ancient city around him, it’s imbued throughout with admiration for what is very old, spiked everywhere with skeptical humor that somehow doesn’t diminish that admiration.

*

Even in the nineteenth century, when Iceland was the poorest country in Europe, everyone there could read. The relationship between Icelanders and their literature and language can seem to foreigners a little insane. “This may seem strange,” one Icelander told an American television reporter in the 1980s, “but the Icelandic language is the very reason why we are staying here.” Contrary to Laxness’s doomy feelings about his impact on his countrymen, the week he died, an appreciation of his work in the country’s leading newspaper concluded, “The day Icelanders forget the writing genius of Halldór Kiljan Laxness, they will no longer fulfill their role as a nation.”

Icelanders speak one of the world’s oldest languages in continuous use and elect representatives to a parliament that has a claim to being the world’s oldest surviving legislative body. But geologically the country could hardly be younger, being entirely volcanic. Don’t bother looking for fossils; almost no sedimentary rock has had time to form. The sagas of Icelanders—plotty, laconic, often heart-rending—constitute one of the oldest literatures in any language still commonly spoken. Laxness was the heir not only to the language and setting of the sagas but to their humanity, their outrageous understatement and charm. Nonetheless, reading his novels even decades after his death, they land on the mind with the shock of the new. Readers who think they know the limits of Laxnessian style or what he seemed to believe will keep being surprised.

Throughout his career Laxness changed his mind about nearly everything that mattered to him. Politics, religion, love, prose style. He seemed to thrive on the meat of his own sacred cows. While he was working on A Parish Chronicle, he wrote to a Swedish scholar, “I have had a little novel in the works since the autumn, driven on by the same need for renewal that has always plagued me.”

A Parish Chronicle would be published in the original Icelandic in 1970. It is presented here in English for the first time. It represents yet another radical shift, in narrative perspective and ideals, for a man who never came close to writing the same book twice. It is his only novel in which he himself appears, all but invisibly, like a sprite.

Crammed with humor and pathos, it tells the story of a church bell as much as of a parish and a nation. Centuries ago in Mosfellsdalur Valley, near the farm called Laxnes (where the writer born Halldór Guðjónsson grew up and from which he later took his name), a little church is ordered demolished by the Danish crown in order to consolidate the parish with another nearby. More than a century passes before the authorities arrange to carry out the decree. But a few of the locals will have none of it.

If Laxness often wrote about what was wicked, ugly, even horrifying, he did so out of a habit of finding beauty in little else.

Their cunning, and their persistence in holding onto what remains of their patrimony after the church is leveled, may go a little way toward explaining to foreigners how Icelanders have managed to survive in such a treeless, wind-scoured, famine-prone place for more than a millennium, or how they have maintained a language mostly unchanged since the time of the Viking raiders who first settled there.

The reader may wonder how much of this book is true, in the most secular and least inspired sense of the word. In fact many of the characters—even Big Gunna, one of the great larger-than-life paupers of Laxness’s oeuvre—did live in Mosfellsdalur and went by the names Laxness gives them in the book. Nevertheless, the first Icelandic edition included the prefatory note, “References to named individuals writings documents places times and events do not serve a historical purpose in this text.” He plainly didn’t let the historical record impede invention.

*

Laxness was a writer and a person of unembarrassed self-contradictions, a patriot given to blistering criticism of his countrymen; a doting father who in his twenties got a farm servant pregnant and seldom had anything to do with the daughter who came of it; a loyal friend who published a fawning defense of the Soviet state even after he had watched the secret police abduct one of his comrades from her Moscow apartment in the dead of night and take away her infant daughter during the Great Terror. We know this because he wrote about it, after he changed his mind about Stalin too.

If Laxness often wrote about what was wicked, ugly, even horrifying, he did so out of a habit of finding beauty in little else. As he said of one of his protagonists, his “cause was evil from almost every point of view except his heroism.” The challenge that some readers confront when starting his bigger books—on which A Parish Chronicle may work for future English-language readers as an urgent inducement to get moving—is sometimes whether they want to endure so much hardship and cruelty on nearly every page. But his heart never leaves these people, and the experience of reading him is of a singular, wry, unstinting sympathy especially for characters at their most blockheaded or deranged.

This contrast opens the territory for the kind of humor and pity he is so good at. “I don’t think a person needs to be eating all the time…It’s a bad habit,” says Gunna, who has just nearly died of exposure and has not eaten in three days.

A Parish Chronicle is a late vein of Laxnessism, as free of his previous ideological entanglements as he could make it. Around the time it was published, when a television interviewer asked if he had betrayed his youthful ideals, he answered, “I hope so.” Here, he’s as humane as ever, as interested in human folly, but now much less interested in correcting it. It is the work of a writer with nothing to prove, only to tell. It looks from the outside like a modest book. It turns out to be a major book in the grandness of its modesty.

__________________________________

From A Parish Chronicle by Halldór Laxness, translated from Icelandic by Philip Roughton. Copyright © 2026. Introduction copyright © 2025 by Salvatore Scibona. Available from Archipelago Books.

Salvatore Scibona

Salvatore Scibona is the recipient of a Mildred and Harold Strauss Living award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His first novel, The End, was a finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the Young Lions Fiction Award. His second novel, The Volunteer, was called a “masterpiece” by the New York Times and won the Ohioana Book Award. His books have been published in ten languages. His work has won a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Pushcart Prize, an O. Henry Award, and a Whiting Award; and the New Yorker named him one of its "20 Under 40" fiction writers. He is the Sue Ann and John Weinberg Director of the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library.