A Riveting, Timeless Journey Through the Afterlife: Inside the World of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Michael Palma on the Contemporary Relevance of Italian Literature’s Founding Masterpiece

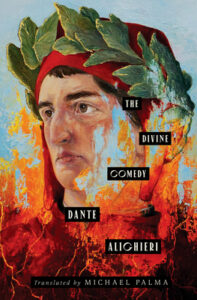

Go to the poetry section of any reasonably well-stocked bookstore, and you will find Dante’s Divine Comedy represented in a number of translations of widely varying vintages and styles. Over the last two centuries and especially in the last three or four decades, both the complete Comedy and the Inferno in particular have been rendered into English more frequently than any other work of literature. New studies and—despite the relative scarcity of reliable information—biographies of Dante continue to appear each year, and videos of lectures, readings, and other Dante-related presentations are everywhere online.

The enduring popularity of The Divine Comedy is an extraordinary, perhaps even puzzling, phenomenon. It is, after all, an intricately rhymed poem of more than 14,000 lines, which, despite the directness of the writing, veers at times into syntactical snarls almost as tangled as the dark wood in which the protagonist finds himself in the opening lines. The Comedy is written in terza rima, or “third rhyme,” a form created by Dante for this work.

Terza rima is composed of three-line units called tercets, in each of which the first and third lines rhyme with one another and the second line rhymes with the first and third lines of the following tercet, thus creating components that are simultaneously independent and interlocking. Metrically, it is written in hendecasyllabics, or eleven-syllable lines, in which every other syllable, beginning with the second, is stressed—a measure that corresponds to English iambic pentameter. The poem’s formal complexity could have been an impediment preventing most readers from ever approaching it, let alone enjoying it. And yet, from the time when its separate canticles began circulating in the last few years of Dante’s life, it has been, and continues to be, undeniably popular.

It is no wonder that the Internet abounds in reviews from readers who started the Divine Comedy expecting to be bored or confused but who instead have found themselves riveted.

What makes the popularity of the Comedy even more extraordinary is the amount of information outside the poem that is needed for even a moderate comprehension of it. It is filled with biblical, classical, and mythological allusions, many of which are given only the briefest of mentions, in some instances not much more than a name or two; Dante is clearly writing in the expectation that his intended audience of learned men will know these references and understand their relevance, a confidence that nowadays can be extended only to specialists in these various fields.

While the classification of the categories of sins and their punishments in the Inferno is relatively straightforward, the Paradiso contains some extended and at times abstract discussions of classical and early Christian philosophy. A good many of the characters who appear in the Comedy, their actions and situations, and their relevance to the poem’s larger thematic concerns cannot be fully understood without detailed reference to political, military, and ecclesiastical events in thirteenth-century Europe. Our comprehension and appreciation of the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Aeneid are enhanced by understanding the mythological allusions found on almost every page and the cultural contexts in which these epics are grounded, and most translations of them provide elucidations of such references.

Nonetheless, focused as they are upon character and event, these great works can be largely understood and enjoyed without going beyond the texts themselves, and there have been estimable versions of all three, such as those by Robert Fitzgerald, published with no annotations. An unannotated Divine Comedy—even though there are several available—is almost unimaginable.

Yet, when the issue is considered in a larger context, the enduring popularity of Dante’s great work is not at all surprising. On the most immediate level, the poem tells a strikingly original and fascinating story. Carried forward by its constantly changing scenes and characters, we keep turning the pages in our eagerness to know what is going to happen next. Those scenes are endlessly inventive and those characters are complex and psychologically convincing human beings, with whom the poem’s narrator has a number of vivid and memorable exchanges.

These encounters stir in him a broad range of emotional responses, from tender pity to bitter anger to savage satisfaction. Much of the way, especially in the earlier parts, this clear, easy-to-follow story is told in a simple, direct style. That style is an amazingly flexible, infinitely modulated instrument, capable of shifting almost instantly from straightforward narrative to intricate description, from inspiring sublimity to shocking vulgarity, from extravagant rhetorical devices to dialogue of intense and heartrending directness.

If it gave us no more than this, the Divine Comedy would remain a perpetually compelling and enjoyable work. But it gives a great deal more. It provides us with a detailed view of the politics and the problems, the social context and the customs, of Dante’s time and place. It contains extended philosophical and theological discussions that engage—as do all truly great works of literature—the central issues of human existence: what we are, how we live, and how we should live. All of this material is integrated into a unified imaginative universe of astonishing richness and texture.

Although Dante’s epic is a work of much greater artistry and profundity, it is in some ways an ancestor of The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, Star Wars, and other such worlds in which so many young people immerse themselves today. It is no wonder that the Internet abounds in reviews from readers who started the Divine Comedy expecting to be bored or confused but who instead have found themselves riveted.

*

Given its presence in our culture, we come to Dante’s masterwork with a number of assumptions, several of which call for some examination. Like the titles Les Misérables or Great Expectations, Divine Comedy is one whose familiarity has led us to take it for granted, without stopping to consider its implications or its relevance to the work in question, but each of its words is worth a moment of consideration.

Dante called his masterwork simply the Commedia, or the Comedy; it was later editors, in the sixteenth century, who added the adjective Divina—a word that has since become all but inseparable from it—to acknowledge both its theologically significant subject and its divinely inspired artistic achievement. And Comedy here does not connote mirth and laughter (there are instances of humor in Dante’s verses, but humor is, of course, far from the dominant mode or mood of the poem).

In classical terms, comedy signifies first a work written in the low, or common, style—in Dante’s case, his local Tuscan dialect, rather than Latin. It also denotes a work which finds the protagonist in difficult circumstances at the outset but which tends toward a happy ending—in this case, the availability of eternal salvation to the protagonist, and to all who truly desire it. Thus, the Comedy ultimately reinforces the comic view of life, the idea that we have at our disposal and in our natures the means to bring about a favorable outcome, as opposed to the tragic view that the combined forces of fate, fortune, and our own frailty will destroy us in the end.

The historical Italy of most of our imaginings is essentially that of the Renaissance, whose name denotes a “rebirth” of learning and connotes an emphasis on humanism. Opinions differ as to when the Renaissance may be said to properly begin, but even the earliest estimation postdates Dante’s life and death by decades. Dante’s world was that of the Middle Ages—and here we must be careful to avoid the misconception that the term “Middle Ages” is synonymous with “Dark Ages,” with cartoonish implications of filth, brutish ignorance, and constant, reflexive violence.

All of these things existed, of course, as they do in any time and place, including our own. But Dante’s world was also one of great learning and sophistication, of subtlety and refinement, of familiarity with and reverence for the cultural heritage of the past. While there were many world-changing discoveries still to be made, there was more geographical awareness and even scientific understanding than we might assume.

Nonetheless, even though it can hardly be claimed that most people’s lives were lived under imminent threat of violence, the thirteenth century was a remarkably bloody time in Dante’s corner of Europe. Violence was disturbingly frequent on a personal level, as shown by the high proportion of monarchs and other rulers appearing in the Comedy who were sent into the afterlife through murder and assassination. Warfare was constant, between, and within, neighboring city-states as well as between distant realms. Italy was not forged into a unified, modern nation until the Risorgimento of the 1860s.

Beginning in the twelfth century, central and northern Italy was organized into a patchwork of independent entities composed of a central city and its surrounding smaller communities. Some were ruled by princes and other authoritarian figures; others, including Dante’s Florence, were republics. Each of these was small enough for its most prominent citizens to be personally acquainted with one another and for there to be a strong element of social cohesiveness.

Of course there are many other ways in which Dante’s was a time very much unlike our own. Needless to say, all of the technological breakthroughs that are the basis of the comforts and conveniences of our daily lives, from indoor plumbing to electricity and everything that depends upon it, lay centuries in the future. At several places in the Inferno, Dante remarks upon the stench emanating from this or that location; one wonders how strong these smells must have had to be, since the hygiene of his time, both public and personal, was rudimentary and foul odors would have been a constant of daily life.

By our standards, medical care was almost nonexistent, and many conditions that nowadays are routinely cured or prevented would have been inevitably fatal; not all of the souls in the Comedy who died in their thirties and forties had met violent deaths. The social mobility of our society, on which we pride ourselves with varying degrees of justification, was extremely rare; the patterns of most people’s entire lives could have been confidently predicted from the moment of birth, and Dante found rising from one’s origins a phenomenon noteworthy enough to be commented on: “a Bernardin / di Fosco in Faenza sprouting high / from low seed” (Purgatorio, Canto XIV).

The view is expressed, at the end of Canto VIII of the Paradiso, that society functions most harmoniously when all recognize and accept their proper, divinely ordained roles. In a world in which everyone has a predetermined part to play, there is much less tendency to blame others for failing to improve their lot or to arrogantly judge them as failed versions of oneself: Dante’s numerous allusions to laborers and peasants are totally free of condescension.

Given the fact that the great majority of people endured lives that were brief, harsh, and exhausting, it is little wonder that those who were not irredeemably terrified of eternal damnation would seek comfort in a belief system which promised that suffering was redemptive and that all would be made right in eternity. Indeed, the single most important component of the poem’s European context is the universality of Christian belief and the authority of its church.

In the millennium since the Edict of Milan (313) had established tolerance for Christianity in the Roman Empire, the previously persecuted sect had grown and taken hold to the point where the Roman Catholic Church dominated virtually every aspect of life in western Europe (there were heretics and schisms, but the Protestant Reformation was still two hundred years in the future). Life on earth was seen as a prelude to the eternal life that followed after death, and the manner in which one lived while upon the earth determined where, and under what conditions, that eternal existence would be spent.

The domination of this religious emphasis extended to learning and the arts as well. Since the majority of people were uneducated and illiterate, the visual and plastic arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture were especially significant as embodiments of the spiritual dimension. Literacy and learning were essentially the province of spiritual and secular authority, and, to Dante’s anguish and near despair, the line between the authority of the church and the authority of temporal government was becoming increasingly blurred.

*

The fictional character who undertakes this obviously fictional journey through the afterlife of his imagining shares his name and a great deal of his history with his creator. Still, readers who come to the text for the first time may be surprised to discover the extent of its autobiographical dimension. Like John Milton, the author of the other great Christian epic, Paradise Lost, Dante weaves a considerable amount of personal information into ostensibly objective and universal works.

But while Milton tends to confine himself to occasional asides or, as in Samson Agonistes, to situations that parallel his own circumstances, Dante, in making himself the central character of his own poem, assigns equally significant roles to his time and place. Many of the souls that Dante encounters among the dead are historical and mythological figures, but many others are public figures of his own time and even personal acquaintances of his.

Much of this material would have been familiar to his original readers (and some of it would not: extensive commentaries on the Comedy began to be written within decades of its completion), but very little of it is common knowledge nowadays. To comprehend the scope of Dante’s intentions, we need an understanding of his life and times and of the political and religious situation out of which the poem grew.

Dante Alighieri was born in Florence in 1265, sometime between mid-May and mid-June: he tells us in Canto XXII of the Paradiso that he was born under the sign of Gemini. Thus, in April 1300, when the Comedy is set, Dante was nearing his thirty-fifth birthday, which would place him exactly “midway through” the journey of the “threescore years and ten” that the Ninetieth Psalm describes as the span of a human life. While of modest financial circumstances, his family was of notable lineage; his great-great-grandfather Cacciaguida degli Elisei (whom he encounters among the blessed in the Paradiso) had been a cavalier and a crusader.

While Dante was still young, both of his parents died—his mother, Gabriella, known as Bella, when he was still under ten years of age; his father, Alighiero di Bellincione degli Alighieri, a moneylender and a renter of property both in the city and beyond, when Dante was about eighteen. Dante’s father remarried after Bella’s death; sources differ as to how many children he had with each of his wives. In 1277, at the age of twelve, Dante was betrothed to Gemma di Manetto Donati. Their marriage, which took place around 1285, produced three sons, as well as a daughter who later became a nun under the name of Beatrice. Dante never mentions Gemma in his writings, and it has been traditionally, but not necessarily reliably, assumed that their relationship was not a close one.

According to Dante’s own testimony in the Vita nuova (New Life), a gathering of thirty-one poems set within the framework of a narrative and a commentary upon them, the most important relationship of his life began when, at the age of nearly nine, he first beheld an eight-year-old girl named Beatrice. Beginning with one of the first biographies of Dante, written a quarter-century after his death by Giovanni Boccaccio, author of the Decameron, she has been identified with Beatrice Portinari, who married a wealthy banker named Simone de’ Bardi, had several children, and died in 1290 at the age of twenty-four.

But even if we had much more factual information, it would of course be impossible to determine the precise relation between autobiography and mythmaking in the Vita nuova, or, for that matter, in the Comedy itself. In the earlier work, which dates in all likelihood from his late twenties, Dante describes an intense love sustained on the slightest and most occasional of contacts, which gradually deepened and transformed itself as the lover came to terms with defects in his own nature, and which led to a resolve, after the death of his beloved, not to write of her again until he could do so in a way that would be worthy of her.

In his twenties and thirties, Dante took an increasingly active part in the public affairs of his city. In June 1289, he was a cavalryman at the Battle of Campaldino, in which the Florentine forces routed those of the province of Arezzo. At that time, it was necessary to be enrolled in one of the city’s professional guilds to take part in Florentine politics, so in 1295 Dante became a member of the Apothecaries’ Guild, which was open to poets and men of learning.

Over the next several years he spoke frequently in official meetings and was appointed to several municipal positions, including his selection in June 1300 as a prior, one of the city’s six-member governing council. Dante had an active interest and involvement in politics throughout his adult life, which would culminate in the infliction of traumatic damage upon his public career and the entire course of his life through the machinations of his political enemies. It is not at all surprising, then, that he has seen fit to place a number of those enemies, including some who were not even dead yet, at various levels of Hell, or that a century’s worth of political and military strife is thoroughly ingrained in the text and texture of the Comedy.

Many of the dead souls encountered by Dante had taken part in the seemingly endless power struggles between two opposing factions: the Guelphs, who were supporters of the increasing temporal power of the papacy, and the Ghibellines, supporters of the Holy Roman Empire as the legitimate secular authority. The controversy between them had begun in 1075, when Pope Gregory VII asserted that the papacy had authority over secular matters and authorities as well as spiritual ones. The Italian names of the opposing parties derived from the German factions of Welf and Waiblinger, whose struggle originated when the archbishops of Mainz and Cologne prevented the accession of Frederick of Swabia, the hereditary successor to the throne of the empire, in 1125. A century later, the divisions which that struggle exposed began to inflame the city of Florence and there to take on a life of their own.

[Dante] is holding out for adherence to the highest possible standards, no matter what the cost, in a world in which hypocrisy, expediency, and self-serving seem to be the surest roads to success.

These tensions flared into open strife in 1215, when a Florentine nobleman was murdered to avenge the insult of his having broken his engagement to the daughter of another powerful family—an incident alluded to several times in the Comedy, and one whose implications reverberate throughout the text. For the next half century, the two factions took turns expelling one another from the city and establishing control over its affairs. In 1266, the year after Dante’s birth, Charles of Anjou, acting on behalf of the pope, opposed Manfred, illegitimate son of Emperor Frederick II, at the Battle of Benevento.

Frederick had been deposed by Pope Innocent IV in 1245 and died in 1250, leaving the imperial throne vacant until 1308. With Manfred’s defeat and death, the Ghibellines were effectively destroyed as a political force in Florence, and the city thereafter enjoyed a quarter century of relative stability. But in the 1290s factionalism revived and the Guelphs were split into opposing groups: the Blacks, led by the wealthy and powerful Donati family, to whom Dante was related by marriage, and the Whites, who evolved into Ghibellinism as Pope Boniface VIII sided with the Blacks to consolidate his power. Dante allied himself with the Whites, since he regarded the empire as the divine instrument of temporal authority and fiercely decried (including several times in all three canticles of the Comedy) the corruption wrought within the church by its pursuit and exercise of secular power.

On June 9, 1301, Florence’s city council took up a request by Pope Boniface VIII for two hundred cavalrymen to assist him in securing territories in southern Tuscany. While others expressed less than wholehearted enthusiasm, Dante was the only member of the council to speak out unequivocally against the proposal. In September, he angered the pope again when he refused to support Boniface’s invitation of French forces into Italy. A month later, Dante was part of a three-man delegation sent to Rome to attempt to conciliate the pope.

After their meeting, Dante was detained by Boniface and effectively prevented from returning home with his two companions. In his absence, on November 1, Charles of Valois, with the pope’s backing, led his army into Florence, and Dante’s political enemies took complete control of the city. On January 27, 1302, Dante was tried and convicted in absentia on trumped-up charges of financial corruption and defiance of the pope, stripped of all his property, and banished from Florence.

He refused to stoop to answering the charges against him, and, despite his sporadic hopes of negotiating an end to his exile, the banishment was later intensified to include a sentence of death should he be found inside the city. He never saw Florence again. Boniface, who died in 1303, comes in for particular obloquy in the Comedy, with Dante missing no opportunity to abuse him for his corruption. Although Boniface was still alive in April 1300, when the poem takes place, in Canto XIX of the Inferno Dante shows us the precise spot in Hell that is waiting for him.

During his years of exile, Dante wandered restlessly through northern Italy, spending time in Lucca, Padua, and Bologna, taking up an extended residence (1312−1318) in Verona, and settling finally in Ravenna, where he died, probably of malarial fever, on September 13, 1321. He began the Inferno around 1308, and completed it by 1314, when he had handwritten copies of the text made and circulated, the method of publication in the pre-Gutenberg era. Copies of the Purgatorio had begun to appear by 1318, and Dante completed the Paradiso only months before his death.

*

The Divine Comedy is a work of stunning imagination and astounding complexity and variety. Yet one of its most astonishing features is its basic unity, with extended discussions of theology and history interwoven with the presentation of a gallery of unforgettable characters who display the entire range of human nature, everywhere enriched by a remarkable depth of insight and breadth of understanding.

And then there are the frequent and famous similes, ranging from a line or two to nearly a page, that appear throughout the text. Comparisons drawn from topography, history, myth, and even domestic life give the work an amplitude it might not otherwise possess, as well as providing us with some remarkably detailed descriptions of what daily life was like in Dante’s Italy. All of these, and more, he seeks to integrate into a comprehensive whole, so comprehensive that mythological figures are invested with a reality equal to that of historical ones.

Dante’s detractors—and there are some—frequently voice the canard that he has populated Hell almost exclusively with thirteenth-century Florentines, a claim that in their view renders the Divine Comedy more provincial than universal, more petty than ennobling. Undeniably, these Florentines are the majority of the souls he interacts with; yet, as he points out in several places, although there are innumerable thousands of others to be seen everywhere, these are the only ones he can converse with in his own language.

It is undeniable that Dante is taking revenge, with the limited means available to him, on those who have destroyed his life, and that he is seeking relief from the pains, both physical and psychological, of his situation. And clearly he is consoling himself that there is a higher order in the universe, one in which justice will be done at last, in which all losses are restored and sorrows end. These are all, arguably, elements of self-interest.

But, on a much deeper level, he is lamenting the disorder that engulfs his life, his country, and his church, and by extension, all of humanity. He is holding out for adherence to the highest possible standards, no matter what the cost, in a world in which hypocrisy, expediency, and self-serving seem to be the surest roads to success. He is, we may say, trying to keep his head while all about him are losing theirs. For all these reasons, and so many others, the Divine Comedy ultimately radiates a depth and a dignity that nothing can diminish.

__________________________________

From The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri, translated by Michael Palma. Copyright © 2024. Available from Liveright, an imprint of W.W. Norton & Company.

Michael Palma

Michael Palma has published six collections of original poetry and nearly twenty books of translations of modern and contemporary poets. He has received numerous awards, including the Italo Calvino Award from the Translation Center of Columbia University. His most recent book is Faithful in My Fashion: Essays on the Translation of Poetry. He lives in Vermont.