A Rare Book Exhibition Celebrates Historic Contributions by Women

Scientific Discoveries, Women-Only Climbing Clubs, and Much More

In his 1930 work on book collecting, Anatomy of Bibliomania, Holbrook Jackson claimed that “book love is as masculine (although not as common) as growing a beard.” The late 19th century had seen book collecting as a hobby gain extraordinary popularity among gentlemen of the upper and middle classes of British society and, as evidenced by Jackson’s quote, the sphere of book collecting was still viewed as almost exclusively masculine into the early 20th century.

And yet, the presence of female figures throughout history who did take an interest in book collecting, as voracious and ambitious as any of their male counterparts, is evident. From Fatima al-Fehri, who founded what is now the world’s oldest functioning library in 859 CE, to Queen Elizabeth I, whose passion for books saw her lavishly hand-embroider several of her own collection, women-bibliophiles are by no means absent from the pages of history.

Items included in Peter Harrington’s new catalog and accompanying exhibition, In Her Own Words: Works by Exceptional Women, provide ample evidence that books are indeed a woman’s game. An inventory of the great library of England’s first acknowledged female bibliophile, Frances Mary Richardson Currer, from Eshton Hall in Yorkshire, attests to the presence, and even pre-eminence, of women book collectors in the 19th century. A rare typed letter is signed by legendary New York librarian Belle da Costa Greene, the architect of the Pierpont Morgan library. Sylvia Beach’s memoir about famous Paris bookshop Shakespeare & Company, which she founded in 1919, sits alongside first editions of the three works with which Margaret Busby, Britain’s youngest and first black woman book publisher, launched her publishing house.

Created in recognition of the recent groundswell of interest in works by and about women in the rare book world, this interdisciplinary catalog brings together the work of exceptional figures, spanning the fields of literature, politics, philosophy, economics, science, travel, and the arts. Works by familiar names such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Agatha Christie and J.K. Rowling, represent milestones in women’s excellence in the printed word. But it is some of the more obscure material in this catalog which, when explored in more detail, tells the most extraordinary stories: often unremembered women throughout history who, despite financial, social and political impediments, despite prejudice and opposition, excelled and conquered.

This catalog acknowledges the women who fought for the rights we enjoy today: suffragettes and activists, lawyers and economists. Millicent Garrett Fawcett signed the copy of The Women’s Victory that can be found in the catalog in July 1928, the same month the Equal Franchise Act gave British women electoral equality with men. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s feminist Utopian novel Herland is inscribed to Californian suffragette Alice Locke Park, who was instrumental in gaining the vote for Californian women in 1911. An anti-nuclear postcard, one of a series issues by The Women’s Press in 1982, asks “who will inherit the earth?”

In Her Own Words is just one contribution among a number of recent and forthcoming catalogs from prominent booksellers focusing on work by women. Efforts such as these will continue to diversify the rare book trade as a whole, reinvigorating existing collectors and inspiring new ones, reclaiming and revaluing work by forgotten or unexplored figures and, crucially, adding a new, female perspective to the understanding of our shared cultural history.

We asked women booksellers from Peter Harrington to explore in more detail some of their favorite items from the catalog.

–Rachel Chanter

*

Theodora Robinson

The Pinnacle Club Journal was a great find—the first fifteen journals published by one of the earliest British women-only climbing clubs. It was founded in 1921, at a time when women were excluded from most climbing clubs, by Emily “Pat” Kelly. She wanted women to be able to learn to climb independently and not rely on the help of men, however kindly intended. While we’ve come a long way, sport is an area where we’ve still got to make massive strides to achieve anything close to equality with men. This is a beautiful example of an extraordinary community of women pushing their boundaries in sport.

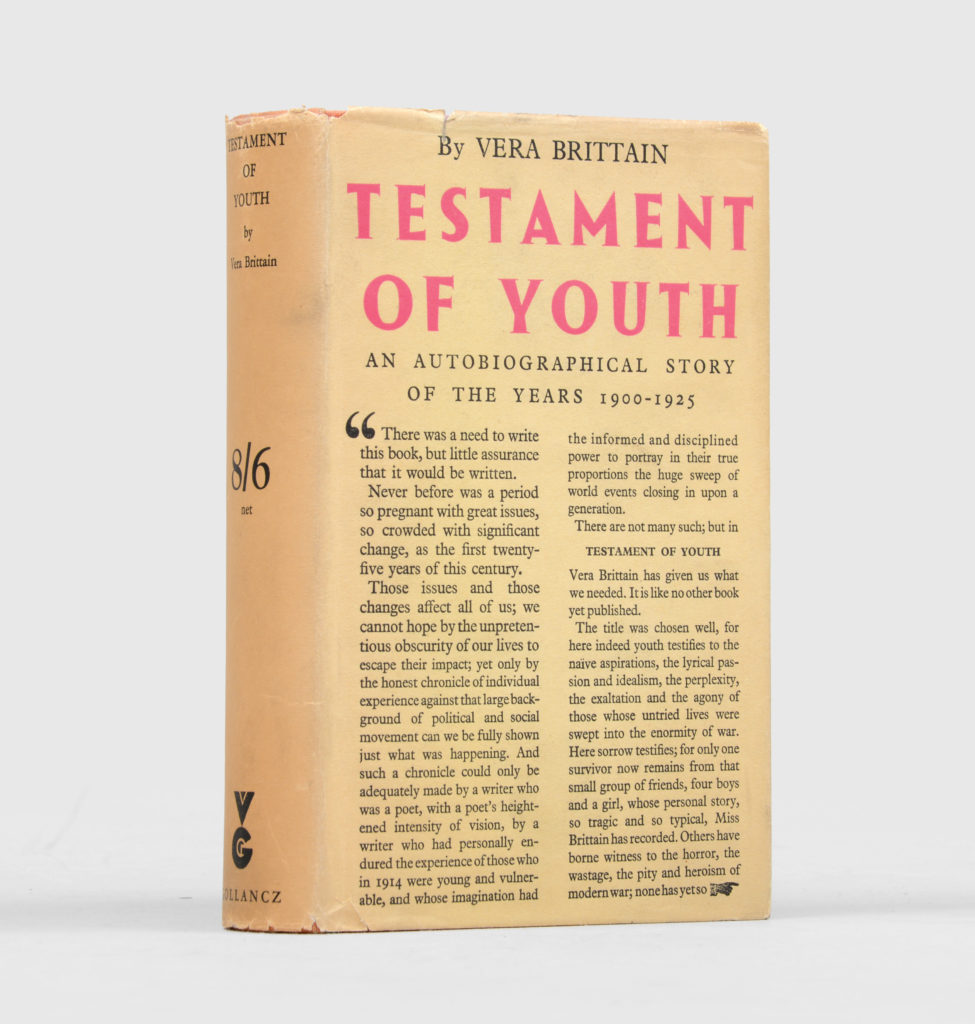

Finding Testament of Youth, Vera Brittain’s phenomenal feminist memoir, in the rare dust jacket, was another personal highlight. Brittain’s bestselling work was one of the most important pieces of literature to emerge from the First World War, but it was also about so much more than her wartime experiences—it’s the story of her fierce personal struggle to be educated at university, at a time when women weren’t granted degrees. It’s one of my favorite books, and it was a wonderful feeling to hold this copy!

My final pick is the Belle da Costa Greene letter, signed by her on Pierpont Morgan Library letterhead paper, which we paired with a copy of the Festschrift prepared for her by Dorothy Miner. We’d wanted to be able to include something by Greene for a long time, and we found this just as we were making the final selection for the catalog, so it was perfect timing. As J. P. Morgan’s personal librarian, Greene spent four decades building one of the world’s greatest libraries. In a climate of racial prejudice, she concealed her African American heritage (Greene’s mother was from a prominent African-American family in Washington, D.C. and her father was the first African-American student and graduate of Harvard). She was a brilliant woman and a leading figure in the rare book world, renowned for her formidable bargaining powers and outspokenness. It’s unusual to find a letter from Greene: most of her professional correspondence is archived in the collections of the Morgan, and she is believed to have burned all her personal correspondence before her death.

*

Emma Walshe

The thread that ties my three favorite works together is that I approached researching them with very little knowledge of their author’s achievements . . . and I came out the other side thinking, “How on earth do more people not know about her and her insanely important work?”

Maria Gaetana Agnesi springs to mind first, with her Instituzioni analitiche ad uso della gioventu’ Italiana (1748), the first advanced mathematics book by a woman. Agnesi spent over a decade determinedly preparing material for her book, and had a printing press installed in her family home just so that she could supervise the complex typesetting of her equations and diagrams. She became so respected as a mathematician that she was the second woman ever to be granted professorship at a university.

Second up is the 19th-century French feminist Flora Tristan and her Promenades dans Londres (1840), an acclaimed work exposing London’s poverty crisis at the time. Tristan spent her life campaigning for her own personal rights—she fought doggedly to divorce an abusive husband, gain custody of her children, and reclaim her maiden name—and the rights of women everywhere: a true force of nature.

Jocelyn Bell is next, the co-author of a landmark scientific paper documenting what has been called one of the greatest astronomical discoveries of the 20th century, the existence of radio pulsars (1968). Despite the fact that Bell was the first of her team to notice the phenomenon, she was not formally acknowledged when her two male supervisors were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974 for the discovery: a decision regarded now as one of the greatest injustices in the history of the prize. It was a real pleasure to list the work in our catalog under her name—a small but pointed way to recognize her remarkable, and frustratingly overlooked, contribution to her field.

And finally, an honorable mention must go to Ada Lovelace. I don’t think I can claim her to be quite as under-appreciated as Agnesi, Tristan, or Bell—her reputation as the first computer programmer is now fairly well-established—but she still deserves huge respect for producing the most important early paper in the history of computing: her Sketch of the Analytical Engine invented by Charles Babbage (1843).

*

Rachel Chanter

In this catalog, three items and the stories surrounding them stood out to me as profoundly humanizing of the women associated with them. Firstly, the pacifist manifesto Put Up the Sword by the lesser-known Pankhurst daughter Adela. The third daughter of legendary suffragette Emmaline, she initially shared the views of her mother and sisters, but, after becoming increasingly critical of her sister Christabel’s militant tactics, was branded “a very black sheep” and was ultimately packed off to Australia by her family, never to return. Undaunted, Adela achieved a tempestuous status in Australian public life, her erratic views and self-styled Joan of Arc persona frustrating those who attempted to pigeon-hole her politically. Despite her somewhat unfocused agenda, something about being considered too volatile for a family of such indomitable women is intriguing and appeals to me hugely.

The second item which caught my attention is a tintype photograph by “Mrs C. A. N. Smith”, who specialized in ladies’ portraits in New York City in the late 1800s. Unlike the standard portraits of the era, often highly contrived in terms of solemnity of pose and elaborate backdrop, this image appears almost candid. Three smartly dressed women with relaxed, open expressions are caught in the moment, the backdrop apparently unprepared, the edges of the image slightly blurry. It’s the kind of photo you might snap of your friends on your iPhone. There is a charming immediacy to the photograph, making the women seem real and close in a way unusual for an old photograph.

The third item I have chosen is by German-British physician Charlotte Wolff, who wrote some of the earliest academic studies on lesbianism and bisexuality. She also worked extensively in the field of hand-analysis, believing that the hands of individuals were key to understanding personality traits. The book in our catalog, Studies in Hand-Reading, is a curious compromise between palmistry and science. Within, she examines the palms of numerous key contemporary creative figures, including Aldous Huxley, George Bernard Shaw and Virginia Woolf. To see the hand-print of Virginia Woolf preserved in this unusual, unregarded little book is, for me, little short of magic, conjuring her as a living, breathing woman in a way completely unexpected.

*

Suzanna Beaupre

The works we have gathered in conversation for this catalog highlight women, or aspects of women’s characters, which are often overlooked.

Elizabeth Davis, for example, was a fascinating woman whose story I had not heard before working on the catalog. She had a phenomenal life; running away from home, changing her name, touring the world in her role as a ship’s steward, and returning to London when she ran out of money, all before becoming her autobiography’s eponymous “Balaclava nurse” during the Crimean War—at the age of 65. During the war she volunteered in Scutari, working with Florence Nightingale. The two women clashed on a number of occasions, each coming from very different backgrounds, but held a grudging respect for one another, a female relationship often historically ignored.

Nightingale also features in my favorites due to a work which represents a side to her which is not frequently included in her narrative. She has inscribed our copy of The Victoria Regia (a collection of works by authors such as Harriet Martineau, edited by Queen Victoria’s favorite poet Adelaide Procter) to a female friend. The collection was published by Emily Faithfull’s Victoria Press, an organization created for the employment of women as compositors. This copy appeals as it represents a nexus of women’s political and social activities and highlights a network of political women. Both Procter and Faithfull were active women’s rights activists: they helped found the Society for the Promotion of the Employment of Women in 1859, and were members of the Langham Place Group with other noted feminists such as Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon—Nightingale’s first cousin.

An album of photographs and clippings compiled throughout the First World War by a volunteer army nurse, Margaret “Meta” Sophie Hannah, is one that I have grown thoroughly attached to whilst researching. The album, which includes photos of both John Masefield (Margaret worked at the same hospital as him) and King George V and Queen Mary (at a Bastille Day party in which Margaret prominently and relatably features in her handmade tortoise costume), is an incredible historical source made by an incredible woman.

*

Pauline Schol

The works I have chosen to highlight from this catalog relate to the achievements and strength of personality of three women, each extraordinary in their way.

The Diary of Anne Frank is one of the touchstones of 20th century literature, offering an insight into the experience of European Jews that would otherwise be lost to us. It is not only Anne’s chronicling of the persecutions of the Dutch Jewish population and the fear her family experienced whilst in hiding, however, which make this such an important and affecting work. Anne’s direct manner, vivid personality and aspirations as a writer leap off the page, and are what convinced her father, on finding the diary after his internment in Auschwitz, to seek publication for his daughter’s work. This true first edition represents the first engagement of the world with her story.

Our copy of the memoir of suffragist Millicent Garrett Fawcett, detailing the long campaign to gain voting rights for women, was signed by her in July 1928, the month in which the Equal Franchise Act was passed in the UK. This act finally granted the same voting rights to men and women ten years after partial suffrage was achieved. Fawcett was a tireless campaigner in this pursuit, and this book, bearing her own signature, is a symbol of her perseverance, linked directly to a time when she must have felt the triumph of her achievements.

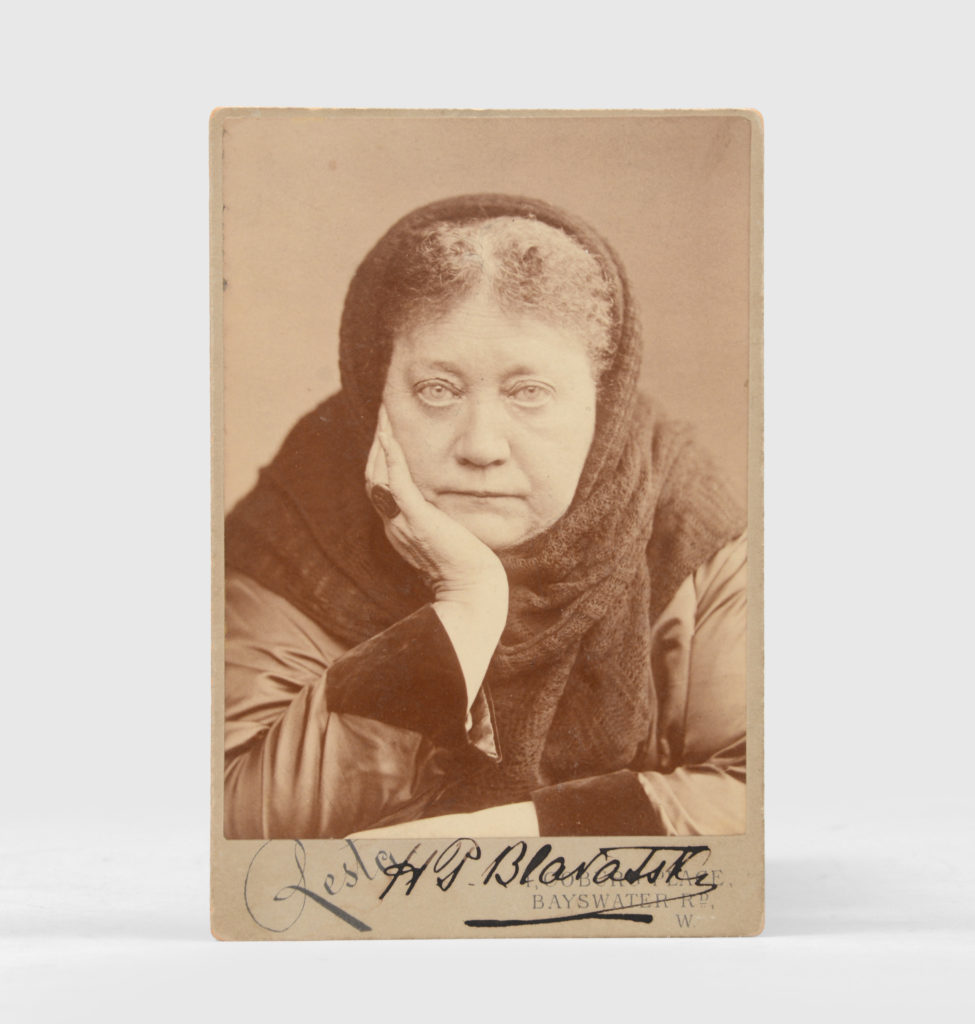

The third item is an enigmatic signed portrait photograph of renowned occultist and founder of theosophy Helena Blavatsky, known as Madame Blavatsky. Born in Russia, Blavatsky came to public attention as a spirit medium, eventually founding the Theosophical Society in 1877. She described Theosophy as “the synthesis of science, religion and philosophy” with the aim of discovering universal truth. This striking photograph, known as the “Sphinx” portrait, draws the eye, Blavatasky’s direct gaze and relaxed pose arresting the viewer. It is a remarkably honest portrait of a woman who lived an unusual life and must have kept a lot of secrets.

*

Items from In Her Own Words are on display in Peter Harrington’s shop in Mayfair, London. Copies of the catalog can be requested via their website.