A Place of Rugged, Simple Beauty: One Summer in Rural Newfoundland

Robert Finch Recalls the Challenging Yet Rewarding Days Spent on Canada’s Rugged Atlantic Coast

After five days of driving and a hundred-mile ferry crossing, I’ve arrived at my destination in the village of Burnside, a tiny outport tucked deep into the inner recesses of Bonavista Bay on the island’s northeast coast, one of the oldest-settled and longest-fished areas in Newfoundland. The landscape is one of low ridges and archipelagos of rocky islands. These hills are the last outpost of the once-mighty and ancient Appalachian range that stretches from northeast Alabama to the tip of Newfoundland’s Northern Peninsula, the ground-down essence of the continent. Here at the edge of the sea, they appear low and half submerged, like the backs of giant black whales frozen in the act of sounding.

Though no longer lofty, at close range these mountains are still impressive and assertive, rising in sheer cliffs hundreds of feet high above the beating surf, bare rock capped by a thin layer of soil and long grassy turf, spilling dozens of small cascades over and down narrow ravines into the sea.

I arrived in Burnside heartsick and heartsore, full of guilt and a pain I could find no release from. I had shattered one life and had not yet built another. I was far from home, and yet felt I had no home. I was in a liminal state of being—in Joseph Campbell’s phrase, “between dreams”—though it felt more like a nightmare than a dream. In other words, I was totally unfit to open myself up to a new place and a new set of people.

Although I had barely arrived here, I felt it was nearly time to go, and I had done nothing.

Yet I knew I had to go, had to get away and try to heal myself in a new place, an unfamiliar world, where the old ghosts could not follow me, or if they did, might become lost in new surroundings. Newfoundland seemed like a good place to go.

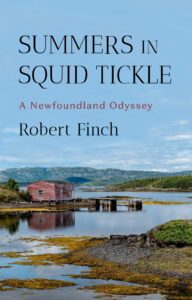

Burnside is a small coastal village, or outport, with perhaps forty or fifty year-round residents, down from three hundred and fifty a generation ago. I’m staying in the western part of the town, which was traditionally known as Squid Tickle. Like many of the names in Newfoundland that strike the visitor as humorous or quaint, Squid Tickle is straightforwardly descriptive. In the center of the town there is a narrow water passage, or “tickle,” separating the Burnside mainland from Squid Island. In the old days there used to be heavy runs of squid in the tickle in late summer, which the local residents gathered and dried.

The house I am staying in belongs to Mark and Fraser Carpenter, two friends who had left Cape Cod and immigrated to Newfoundland eight years ago. In a staggering burst of sustained energy, they built the house themselves in four months, from October to January, living in a camper in the back of a Mazda pickup truck. They worked from sunup to sundown, and when they woke up in the morning their sleeping bags were frozen solid with their sweat.

Over the next seven years they operated a tour boat business in the nearby Terra Nova National Park. Last year they sold the business and were now on a voyage into Arctic waters on the Joshua, a forty-foot sloop whose steel hull they had welded themselves in their driveway and hauled on log rollers down the dirt streets of the town to the harbor. Their enterprise and capacity for work had given them almost legendary status in the town. They generously offered me the use of their house while they were gone.

The house is a modest one-and-a-half-story Cape set on pilings with a crawl space enclosed by boards, built of native spruce and pine lumber that Mark and Fraser cut from the nearby islands. Its Cape Cod design, uncommon here in Newfoundland, immediately gave me a sense of familiarity and some comfort in strange surroundings.

When I first arrived, I literally had to burrow into the house. Since winter gales here will pry open even locked doors, Mark and Fraser had nailed shut their front door and all the windows from inside when they left, exiting through a trapdoor in the pantry and then stacking the crawl space with several cords of “junks”—cut-up spruce and birch stove logs. It took me nearly two hours to toss out enough wood to make a tunnel through which I could crawl to reach the hatch. When I did and poked my head up like a groundhog into the dim kitchen, I found a sweet house, tightly built, with homemade curtains pinned shut across the windows, painted wainscoting, and maps of all kinds covering the walls.

The house fronts a protected cove, shielded from the open water by the western arm of Squid Island. Rock ledges, fringed with rockweed and knotted wrack, are visible at low tide. To the west across Fair and False Bay is a series of low wooded islands backed by a rugged, rocky ridge known as the Bloody Bay Hills. They are not tall enough to be true mountains (none of the hills around here are), but their ruggedness gives them a dimension beyond their actual size.

Before they left, my friends had shut off the power and drained the plumbing, and for the time being I decided to do without them. There was a stone-lined “dug well” just outside the front door that I drew water from in a pail and carried into a large washing tub in the bathroom. This water I used for washing and rinsing dishes. Occasionally I also used it to flush the inside toilet, though most of the time I used the outhouse—or “shithouse,” as most people here unceremoniously refer to it—which has a wonderful view of the water and the northern lights.

For cooking and drinking I obtained water in plastic jugs from a hose at the community center building, formerly the local school, just up the road. Ron Crocker, who runs the Burnside Store, offered to let me put several five-gallon plastic jugs of water in his deep freezer, which I then rotated in my refrigerator every four to five days, thus giving me a functioning icebox with little fuss or mess and no dripping. For light I had a Coleman propane lamp, a kerosene lamp, and candles, which were quite adequate when I arrived, since it grew light by 5 a.m. and didn’t really get dark until after 10 p.m. There was a large woodstove in the kitchen and tons of stove wood under the house, though I rarely had to use it that summer.

One evening a few days after I moved in, I was sitting at the table when I saw through the triptych windows three greater yellowlegs, moving in a group, like friends, picking among the shallows and the knotted wrack in front of the house. Visitors from home, I thought, heading south. All at once I had a panicked sense of the summer passing, of being assaulted with a thousand things to see and learn and do and having no time to do them in, not even the ability to remember what they were. I found myself going about the house making frantic, fragmentary lists, then forgetting where I put them. Although I had barely arrived here, I felt it was nearly time to go, and I had done nothing.

As usual, this inner state was partly a product of outer weather. Here, midway through the human summer, the wild weather and the clear, slanting northern light and the migrating shorebirds all conspired to give me the sense of late September. But it was only the middle of July, and I had nearly another two months to stay. It was time to set about fashioning the rituals and the connections that would take me through the days.

Now, after two weeks here, my days here go something like this: I rise about six thirty or seven, make a cup of tea, and take a walk through the village. Usually this early, I don’t meet any neighbors, since the few active fishermen in the village were up and gone hours ago, and most of the rest are either summer visitors like me or retired.

I pass by the wharves, examine some of the old empty houses, explore some of the rocky points, and enjoy the stunning profusion of wildflowers along the roadsides and in the fields here. Blankets of irises grow everywhere in ditches and low places along the roadsides, and lilacs are still in full bloom in front of several houses. With one sweep of my pocketknife, I gather up a rich bouquet of brilliant lupine, sheep laurel (called “goo-witty” here), daisies, cow vetch, beach pea, wild roses, wild geranium, and bluebells.

After breakfast I usually sit at the kitchen table and write for several hours. When I’m working, I tape a sign on the front door that says “WRITING. PLEASE COME BACK AFTER 12. THANKS.” I’ve had to do this since the common practice in Newfoundland is just to walk into a neighbor’s house without knocking and “yarn” for a while. But when I am simply writing letters, or reading, or practicing my typing, I remove the sign and leave myself open to opportunistic interruption.

Visiting has always been the prime social activity in Newfoundland outports, and Burnside is no exception. Unlike most small towns in the States, there are no public gathering places here. People do not congregate and linger at the post office or the general store—they come and post their mail or pick up groceries and leave. Coffee shops are still rare in the outports, where tea remains the preferred hot beverage. At any rate, in a society where men traditionally set off in small boats at 3:30 or 4 a.m., “bilin’ up” water for tea in a small stove as they rowed or motored to their fishing berths, such places had no function. When the men were away in summer on the Labrador, the women visited one another at their houses, and when the men were home, in winter, they worked together cutting firewood in the woods or mending nets in the “stores”—small sheds built on the individual wharves for “storing” fishing equipment.

Though I was a CFA, or “come from away,” I soon found I had an entrée into the social life of the town simply by living in Mark and Fraser’s house. They were two people known and admired by most of the residents. In addition, they had told most of their friends about me, and left me a detailed map of the town with names and notes about the residents of the houses. Thus, I had a mental picture of the community even before I had met its inhabitants.

I make a daily circuit walk along the hardened dirt roads of the town: up past my next-door neighbors, Bert and Laura Burden, left at the corner and down to the Oldford family’s stage and wharf along the shore, then right on a muddy path around the shore to the small plank bridge across the tickle to Squid Island, then right again to Jim and Jessie Moss’s house and the village post office.

The Burnside post office is a small one-room wooden building profusely planted with flowers all around it. The postmistress, Christine Moss, is Jim and Jessie’s niece-in-law, and lives in the house next to the post office with her fisherman husband, Howard. One enters a tiny vestibule and pushes a buzzer, which brings Christine out of the house, brushing by you into the “office” proper, where she opens the counter window and, with a smile and a toss of her hair, says, in a cordial tone, “Now, my dear, what can I do for you?”

Now, after two weeks here, my days here go something like this: I rise about six thirty or seven, make a cup of tea, and take a walk through the village.

Back over the tickle, I turn left and follow the shore road up a slight hill past the Burnside Heritage Museum, which the older people in town call “the Hindian place.” The Burnside Heritage Project is the major enterprise in town these days, an archaeological research project, funded by the federal and provincial governments, that began about six years ago and, with Laurie MacLean as its director, has made several major finds of prehistoric Innu and Inuit sites in the area. Most of these sites are reachable only by water, and Laurie hopes to develop the project as a tourist attraction, running regular tour boats to the sites, building a proper museum, running school programs, and so forth. Tourism in general seems to be the hope of the future in Newfoundland now that the fish are gone, and about the only chance of keeping the young people here.

Past the Heritage Project buildings the road curves around to the right and down to the ferry wharf. On most days the only vessel using it is an old wooden-hulled six-car ferry with a loud, clattering, smoky engine that serves St. Brendan’s, the only remaining island community in Bonavista Bay, some eight miles north of Burnside. It usually runs four to six times a day throughout the year, until pack ice locks up the bay for the winter.

At the ferry wharf the road splits three ways: the left road takes me to the eastern part of the town, known as Hollett’s Cove; straight ahead is the highway to Eastport, the nearest town of any size, paved only a few years before.

Turning right and heading back up the hill, I pass on the left “the new cemetery”; then, on the right, the tall, red-peaked roof and steeple of St. Alban’s, the Anglican church and the most imposing structure in the town; on the left is the small community building (formerly the village school); and then the “Burnside Store-Thrifty Grocer,” the only store in town, run by Ron Crocker and his parents, Lonz and Ida.

Ron is a beefy man in his early forties, with thick glasses and a short dark beard, and has the ample appearance and jovial manner of an Elizabethan innkeeper. He commonly greets me with some friendly insult (“Here’s the Yankee boy!”) and conveys the latest news of the town—who is sick, who is visiting, who has a boat for sale, etc.—with my groceries.

After leaving Ron’s I continue down the hill, forking left at the corner by Cleaves Oldford’s house, a large yellow structure with an old-fashioned tepee of long, thin spruce trunks stacked in his yard; then past a common wood-cutting yard on the left with a ring of larch (called “sycamore” here) trees and Ski-Doo trails leading out between them into the marshes, or “mishes,” and the wooded country beyond; then left at the fork onto my road, past Bert and Laura’s again on the right, to the small “old cemetery” on the rise just across the road from my house.

The last house on the road is also the largest in Squid Tickle: an imposing twin-turreted, green-roofed dwelling that sits on top of a rocky point overlooking the bay and dominating that end of the town. Known as the Hiscock House, it looks as if it should belong to the richest man in town, the local fish merchant perhaps, though in fact it has been unoccupied for nearly twenty years.

The nights are cool, and I sleep in the snug ship’s bed in the corner of the bedroom under a down comforter, my head level with a window that looks out on the water. In the morning I start a small fire in the stove to take the chill out of the kitchen, make tea and cook eggs or polenta on the propane camp stove. The world looks clean and new and fresh outside with tall purple irises blanketing the swales and the fringes of the shore and azaleas like banks of rose flames along the roadsides and the fresh new lime tongues of cottonwood leaves fluttering like a cool green stream at the edges of the clearings.

It is a lovely morning now, the wind out of the northeast, the temperature near 70 degrees Fahrenheit. Across the bay clouds sail like fleecy flotillas over the gnarled racks of the Bloody Bay Hills, and the dark ledges in the water around the house are fringed in Ascophyllum the color of spun gold.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Summers in Squid Tickle: A Newfoundland Odyssey by Robert Finch. Copyright © 2025 by Robert Finch. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved. Featured image by Tango7174, under the terms of a GNU Free Document license.

Robert Finch

Robert Finch was an award-winning nature writer, radio journalist, and author of several books about Newfoundland and Cape Cod, including The Outer Beach. He lived on Cape Cod for over fifty years, and spent two decades of summers in Squid Tickle. He died in 2024.