“We spend our life,” said Samuel Beckett, “trying to bring together in the same instant a ray of sunshine and a free bench.” There’s something hugely attractive about the mere idea of a free bench. It suggests pleasant idling, the enjoyable whiling away of a few minutes. Perhaps that freedom is accentuated by the bench’s own immovability, the nature of it being fixed to the ground. It is something about the contrast between our own usual motion and accommodating to a fixed point.

In England people tend to be quietly disappointed if someone sits beside them on a bench, it spoils their solitary moment (being English, of course, they would never in any way express this disappointment). In Mediterranean countries, on the other hand, benches are social spaces, places where the elderly sit and talk and watch the rhythm of urban life. The bench can address a paradox, that of deliberate isolation in a crowd as well as enabling a presence in the public arena, becoming part of the life of the street.

The bench is the most archetypal item of furniture, street or otherwise. Before there were chairs or even tables, there were benches. The very name flows through our language: a judge sits at the bench, quality is benchmarked, the word “bank” derives from the benches (banca) once used to trade from, Parliament has its front, back and cross benchers, while football subs might come off the bench. But the bench we’re concerned with here is a very particular type—the public bench.

Seats have been around in cities for as long as there have been cities. There are benches built into the bases of houses in Pompeii, places for residents to sit outside and mingle with the world, gestures of publicness creating a little fuzzy territory between interior and street. The builders of Renaissance palazzi set stone seats into their walls as a gesture of (very visible) generosity towards the public, while church porches and lichgates had benches which provided shelter and refuge to the homeless, the lawless and to travelers.

But it was only as recently as the 19th century that the public bench became a publicly provided symbol of civic life and the civilized city. The bench suggests the city is a place in which we can belong, without having to consume, that it is not the alienating metropolis of myth but a place capable of gestures of welcome and generosity.

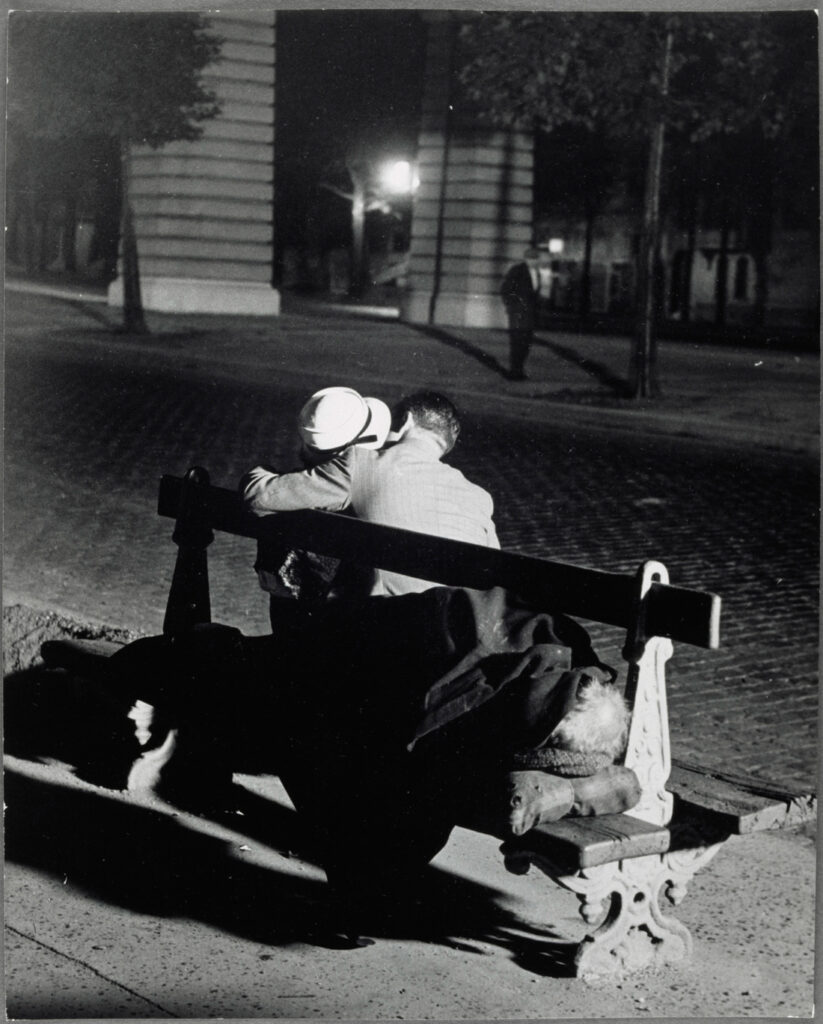

Lovers on a Bench and a Tramp, Boulevard Saint-Jacques, c. 1932, Brassaï.

Lovers on a Bench and a Tramp, Boulevard Saint-Jacques, c. 1932, Brassaï.

That openness to all has made the urban bench one of the most unerringly popular subjects for photographers. Like the bench itself, those occupying it are fixed enough to become a kind of captive audience for the observer of urban life, the observers of urban life themselves observed. The entire range of the human condition and emotion seems to have been captured on benches over the last century or so.

A good place to start might be Brassaï’s photo, Lovers on a Bench and a Tramp, because it captures both sides of the story. The (unusually) hatless man has his arm around the woman, of whom all we see is her hat. At first it seems an intimate embrace, but the more you look the more one-sided it seems to become, a suddenly slightly awkward encounter with the ardor mostly from one direction.

What makes the photo, though, is the man sleeping on the other side, our side. With his overcoat pulled up around his ears, his head resting on an improvised pillow, we see his scruffy white hair. The three people on the bench represent various stages of life and various uses of the city at night. The nighttime bench is unquestioningly accommodating to those with something to hide or nothing to lose, a refuge from polite society. But nothing in the city is ever truly private, attested to by the blurred, burly figure in a flat cap walking by and looking toward the photographer and, in consequence, at us.

From there we might move to the same photographer’s 1936 shot The Riviera. Here we find a single seated man, his head obscured by a white umbrella raised against the sun, separated from the sea by delicate railings in similar white-painted cast iron to the legs of the bench. The bench is in a summer suit, light linen as opposed to the dark worsted of the Paris version. It should be a more cheerful scene than the dark, nighttime shot, but somehow, it is not. This man appears just as isolated against the vastness of the sea. He has found his bench in the sunshine but then has to shelter from it. Between these two shots we have the forms of publicness embedded in the bench.

But not all of its possibilities or combinations. There are also Diane Arbus shots of teenage couples on benches, all attempting to look grown up in their curiously middle-aged clothes, kids in the city grown prematurely mature, the girls in headscarves, the boys in greased quiffs and cardigans. Her wonderful shot Teenage Boy on a Bench in Central Park captures a little of the cool and the cold and the child; the desperation to be seen to not care and the clear penetration of the cold air through to the bones.

Walker Evans captured dozens of images of people sitting on benches, some in comfort, others in drooping desperation. Together they form a painful record of the effects of the Depression but leavened by others embodying the crowded buzz of city social life. The always brilliant Vivian Maier also seemed to delight in scenes on city benches, park furniture as urban stage. Often with her young charges (she was working as a nanny) she would be in the parks anyway, using the opportunity to snap sleeping men or women, their heads leaning slightly back to catch a few rays of sun, their eyes closed against the glare.

Or we might look to Garry Winogrand’s famous crowded 1964 shot World’s Fair, New York which, despite its title, is a photo of a bunch of people on a long bench. If most bench shots display a kind of stasis, this one is full of movement and an almost stagy sense of drama. One young woman covers her mouth as she appears to whisper to her neighbor who, in turn, is cradling the head of what appears to be her sleeping friend. Two other women are looking intently at something out of shot, one putting on her glasses, the other putting up her hair.

On the far left a white woman is in conversation with a black man, while on the far right a besuited fellow is reading the paper. The two men who frame the shot appear calm, in contrast to the heightened states of the women. It is a wonderful composition around which you might weave almost endless stories and scenarios. And the bench, which stretches from one edge to the other, its ends unseen, is the armature supporting the whole thing.

Others from André Kertész and Stanley Kubrick to Weegee and Martin Parr have used scenes on benches to express something of the city from every side, from the melancholy appearance of a broken, empty and unusable bench to the wry scene of dozing pensioners. Sleeping, horizontal or seated bodies appear particularly irresistible, surely because the subjects are unaware and unselfconscious.

The bench can address a paradox, that of deliberate isolation in a crowd as well as enabling a presence in the public arena.In Edinburgh’s Princes Street there is a bench with a brass plaque stating simply: “Remembering J.C.H. Who was often tired.” It is a moment of small pleasure. For others, the tiredness might be more profound, the bench closer to a home. It has always been a haven for the homeless, the last refuge. Laurel and Hardy, the indomitable losers of the Great Depression, articulate this idea in their 1932 film Ladies of the Jury.

The pair are charged with vagrancy. They plead not guilty. “On what grounds?” asks the judge. “We weren’t on the ground,” replies Laurel, “We were on a park bench.” It might not be desirable to the authorities, but one of the critical roles of the bench is that it offers this refuge. While there is a bench, you haven’t yet reached the rock bottom level of the ground.

The bench is a versatile thing, supple enough to embody both that ideal of a welcome place to sit in comfort for a few quiet moments in the park as well as its possibly very different meaning to someone whose last resort it is at night. It is able to change radically from day to night. Increasingly, though, that is itself changing, and benches are being designed and built to discourage rough sleeping, with extra arms and dividers, the kind of thing seen in airports and stations. Huge amounts of thought has clearly been applied to ways in which benches can be made hostile to horizontality.

But sleeping does not necessary mean lying down. Jack London, more famous for his novels than his photography, recorded the poverty that so astonished and dispirited him in London at the very beginning of the 20th century. His photos documented the homeless sitting, rather than lying, on London’s benches. One, showing four men on a bench on the Embankment portrays the camel-sided bench still present today (p.154), another captures a pitiful group of women asleep on benches beside a Spitalfields churchyard.

There are estimated, incidentally, to be over 100 homeless people effectively living at Heathrow airport. Airports may be private spaces and exemplary non-places, but they are also the contemporary city’s gateway default civic space in the way that stations were once. Whole lives are being lived there.

The curious universality and classlessness of the bench has also made it a synecdoche of contemplation in the city. The memorial plaques on benches effectively anthropomorphize them, suggesting that when we park ourselves on a bench we are sitting with the ghosts of all the others who have sat there before us.

Once you start looking in literature and the movies, benches appear everywhere. It is an extraordinary thing, for example, to sit in the Victorian seaside shelter at Margate, on the bench on which T.S. Eliot wrote The Wasteland. You feel the harsh sea wind and a chill penetrates your bones while you peer out at the sea and the big Thanet sky. John Lanchester’s novel, Mr. Phillips, features an executive who has been laid off and, unable to face his wife with the news, spends a day on a bench in Battersea Park contemplating the meaning of life and encountering a tramp who may, or may not, be a performance artist.

From the magical surrealism of Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita to the exploitative dim sentimentalism of Forrest Gump, from Samuel Beckett’s own Watt to The Fault in our Stars, the bench is a ubiquitous device in popular culture. Michelangelo Antonioni’s existentially deep film about shallow people, L’Avventura, ends on a bench. The spy genre too is replete with benches. Here, the park bench in particular becomes the default venue for the surreptitious meeting, the dead drop or the treacherous encounter. It is a public place, difficult to bug. Safe. Which is precisely the essence of the bench, a moment of respite.

In Woody Allen’s Manhattan, the bench looking over at Manhattan through the looming web of the Queensboro Bridge had to be brought in by the production team as the view from the actual pocket park wasn’t quite right. But that is the film’s defining moment, the comprehension of the grandeur of the city from the humble park bench—it became the poster. Perhaps it was inspired by Walker Evans’s shot of a man sleeping on a bench with the Brooklyn Bridge behind him.

Broken Bench, 1962, André Kertész.

Broken Bench, 1962, André Kertész.

The bench is so often a vantage point for the city and, in a way, it melts into the metropolis, a small piece of cityness. So much so that its actual form becomes anonymous. Try to draw a park bench from memory and it is surprisingly difficult. There are myriad bench designs, each vaguely different but each also vaguely similar. That, I suppose, is the point of an archetype. That is not to say there aren’t wonderful exceptions. New York’s Central Park, for instance, provides a wonderful survey of changing tastes in benches.

They start with the 19th-century rustic timber log examples conceived by the park’s designer, Frederick Law Olmsted (attempts to create a romantic version of nature tamed with civilized fittings) and carry on through to Robert Moses’s more functional but still elegant 1930s designs (with their iron-hoop ends) and on to the more self-consciously heritage versions of today. Each carries with it their own idea of modernity: nature and artifice, deliberate modernism, nostalgia for a better era.

Boom time for benches, though, was the mid-19th century. The industrial revolution had made the manufacture of cast iron cheap and easy. The material lent itself to the outdoors and to the complex, florid modeling adored by the Victorians. The extraordinary Egyptian-themed examples inspired by the neighboring Cleopatra’s Needle on London’s Embankment, with seats resting on camels and sphinxes, are among the most enjoyably overblown public benches anywhere. On the opposite side of the river stands another set of benches, their cast-iron ends formed into the shape of swans (although with the very strange modification of lions’ feet).

My favorite design is one from Bishop’s Park in Fulham. It is a deceptively simple design with wooden seat and back and a bent metal frame. Its legs describe an S-shaped curve, its arms a sweeping bow, a little like the chairs in some of the old photos of Paris parks. It looks old, but I don’t think it is. Unselfconscious but elegant, it has few pretensions and is largely comfortable, although its back could have a little more curve and, perhaps, an extra slat. It looks like it belongs in a park. As such a ubiquitous product, the bench has been popular with designers, architects and artists, but few have come up with anything that good. The more designers attempt to design, the more awkward the bench becomes. The generic versions seem to be the best.

Critically, the bench is classless. Particularly a park bench. From well-dressed ladies to homeless men, from horny teens to elderly people-watchers and pigeon-feeders, they come out to just be in the world a little. It exemplifies a certain kind of publicness, a truly democratic intervention and a place to be private in public, a small space in the melee of the metropolis where it is acceptable to do nothing, to consume nothing, to just be. Truly, a free bench is a wonderful thing.

__________________________________

Excerpted from On the Street: In-Between Architecture by Edwin Heathcote. Copyright © 2023. Available from HENI Publishing.