Decades ago, when I graduated from college—in fact, the only time Mom and Dad ever visited Boston—we were at South Station, the three of us sitting on a long wooden bench. I remember it was smoky—or at least dust hung in the sun’s rays through the air. We were having a fight—or at least I was fighting with them. Commencement had been the day before, and I had accompanied them to Amtrak, because they were on their way to DC to make this trip a kind of vacation. Smiling in his smirky way, my father had quizzed me about what I would do now with a college degree in poli sci, when I would start work. He bragged about how he had survived alone in Juárez, after my culo grandfather had slapped 20 dollars into his palm and sent him out the door. I think my father always believed I was kind of soft, too emotional, not his kind of son, not the Mexican macho he adored in Uncle Dago, not the servant he saw in my brother Adán, not the athlete he admired in Pablo.

I was this strange creature who would and would not do what he wanted, who questioned his values to his face, who had created opportunities he only dreamed about, who had finished an American college degree in an American city as strange as Moscow would have been to any of us.

As we sat on that wooden bench and waited for their train, my mother defended my ambiguity, defended my wanting to keep searching for what I truly wanted, which of course, like any smart-ass 21-year-old, I could not articulate very well. This college, this city had opened my eyes beyond Ysleta, beyond El Paso, beyond the border desert, and now just working to pay bills seemed like a prison to me. I knew I would not be able to think, and that’s what I had relished in college for the first time in my life. A certain openness to my life that I did not want to close. His life had been defined by what he had to do; mine would be, I hoped, by what I could do. In his life, he fantasized about becoming a doctor and forever blamed his father for giving him nothing to achieve that dream. In my life, I had taken a rash leap away from home, made my way with little interference from my parents, and would not give up on my nascent dream.

I told my parents I had always felt abandoned and adopted, that they had always favored my brothers and my sister.My father criticized my indecisiveness, my wasting time at school without having a plan. It was more than just that he didn’t want to pay the bills. And really, he hadn’t paid the bills. I had worked every summer, work-study every academic year, I had taken shitloads of student loans, and yes Mom and Dad had sent me hundreds of dollars here and there. But I had carried the load to what I think he saw as a wild gambit in Boston, to this strange, faraway New England school without Mexicans. At graduation, my parents had been the foreigners, much darker than everybody else, with awkward accents, intimidated next to my roommates, friends, and their casually suburban parents.

It wasn’t the money. It was another of my weaknesses, that’s what he used against me at South Station. His green eyes glinted like the edges of Damascus steel. A snide little comment that sliced between my ribs like a switchblade, about my girlfriend, Jean, a blue-eyed beauty from Concord, Massachusetts. My lovely and loving Jean who had sought them out with her college Spanish, and laughed heads-together with my mother; Jean who had accompanied me to El Paso for Thanksgiving my senior year; Jean who was more delicate and sophisticated than the richest Anglo girl they had ever come across in El Paso, Texas.

My father at South Station: “Why would Jean want to stay with someone who doesn’t know what he’s doing? Who doesn’t have a job? It’s time to stop living in a fantasy world. It’s time to be a man.”

I hated him for pitting what he imagined Jean was and what he believed I would never be. I hated him for not believing in me, I hated him for not giving me another chance, I hated him for wanting to slam the door shut on what I could be. I told my mother—because I knew it would hurt her—and I told my father too—because he was next to her—I told them I had always felt abandoned and adopted, that they had always favored my brothers and my sister, that I knew I wasn’t loved by them in Ysleta. I was shouting at them, even as hot tears slashed across my cheeks. I didn’t care that a few others turned to stare at us in that waiting-room cavern. I didn’t care about the propriety or impropriety of what others thought of me, unlike my father. It was the moment when I had felt the most alone in my life, more than that first day as a freshman when I had stumbled with my old suitcases into the dingy, one-room cell, carrying two dozen flautas wrapped in foil from Ysleta.

Thoreau, too, had once been in dark exile in Hollis Hall. I was that iconoclast’s Mexican brother.

Only a few minutes to go, and they would have to leave for their train. I wanted to punch my father. My mother in tears said, of course, she loved me. My father held back, embarrassed, watching both of us as if we were insane, he averting his green eyes from mine. Waiting for him to stand up, I stared through him, my chest heaving in spasms. My mother’s hand reached to hold mine, to calm me. I believed—and did not believe—what I had said. I still wanted to punch him.

I had felt so alone for so many years. Part of it was what I had done by leaving home. Part, too, was having never felt at home in Ysleta. Then my father, inhaling, finally meeting my eyes again, said, “We love you, David, but sometimes we didn’t know what to do with you. You are not like any one of us.”

I think my father said these words because he never wanted to see my mother in pain. I think he said them because he didn’t want to see his grown son angry and out of control at South Station, surrounded by strangers. He may have even meant what he said, too. I don’t know.

We said our goodbyes. I hugged and kissed both of them politely. My head throbbed. I was alone, and I had always been alone, and they had been together and would always be together. It took me years to understand what this meant.

I made many decisions, some awful and others brilliant, but I found ways to keep that openness in my soul that meant more to me than breathing. I told them over the years what I was doing, how I was trying what no one in my family had ever tried to do. When I was failing, I admitted that as well, and they listened politely. I also knew that’s all they could do. One lonely night in Connecticut, I pulled myself from a window’s ledge. No one else next to me. Another day I chose to do something someone like me should have never accomplished, and yet I did, and kept going. I learned to recognize when others, like Jean, were much better than me, because they had faith in my soul. I believed in very little, but I kept going until I would get tired or defeated, and then I would take time to discover another wall to throw myself at. I was, and I am, and I will be, a peculiar kind of immigrant’s son. I got old, and that made everything better, including me.

————————————————

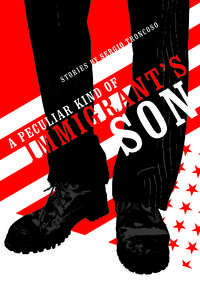

Excerpted from A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son by Sergio Troncoso. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Cinco Puntos Press. Copyright © 2019 by Sergio Troncoso.