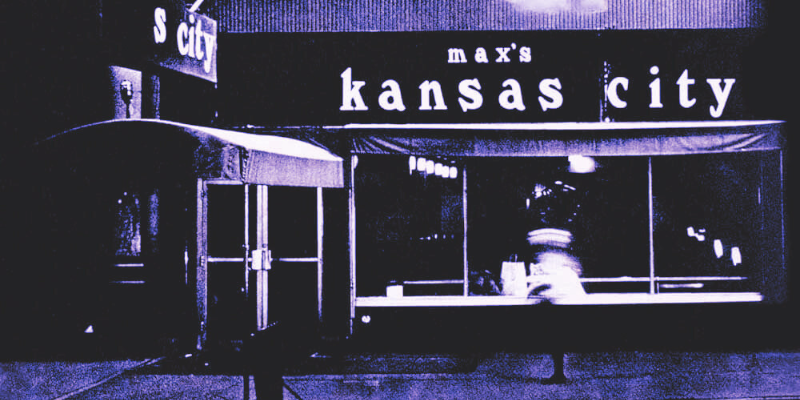

A Night at Max’s Kansas City: Seeing and Being Seen in the 1970s NYC Art World

Pat Lipsky on the Rival Groups of Artists Looking for Fame in Greenwich Village

There were two choices for dinner at Max’s Kansas City: lobster or steak. I always ordered steak. My boyfriend favored lobster. He never paid the tab. After a year or so he gave the owner a sculpture.

Max’s was just north of the Village. Taxi was the preferred mode of arrival. If you lived nearby, it was fine to walk through the surrounding area, which was a wasteland, but the second your driver made that right off Seventeenth Street, there was the oasis of light framed in the club’s big window, and at that moment it felt like catching a reflection of your truest, most energized self in the mirror.

You learned the contradictions: the club’s owner wasn’t named Max—he was a hard-partying man called Mickey. Tall with long, straight black hair and a downturned nose like the nose of a dwarf in a story. Plus a slightly discolored, chipped tooth. He was also unaffiliated with Kansas City. Nearly every night you got out of the cab and walked in there’d be Larry Poons; cheery, noisy, and already drunk Dan Christiansen; and sly, calculating, and handsome Peter Reginato.

You got to know what to expect. The famous car-wreck sculptor John Chamberlain hunched at the bar in his jeans and dark polo; Frosty Meyers, with his punk haircut and walrus mustache; and Larry Zox, heavyset, his wavy hair swept back, signaling for the bartender. Macho guys.

So to find yourself, on a night in Max’s in that unimpeachably right place, with the right people, at the right time: this was unspeakably soothing. It was to be without want.

When you’re young, you expect to mostly mix with others who are young. And then are surprised by the range of ages—late twenties to early forties. The range of backgrounds that brought everyone in was the life of art. And Mickey Ruskin, the non-Kansas non-Max, who had been a lawyer and had then determined, somehow, that life should present one more exciting offer, and had had this wish granted. Art had welcomed him in too.

Mickey, often smiling, had renounced all the sharkiness of his former profession. Even on the issue of billing. Whatever the artists ate and drank was on account. Nobody ever paid. As soon as the number reached into the low thousands they gave Mickey art. Installations dotted the club; it was like a museum, paintings and sculpture that secretly commemorated the appetites.

You’d see women as you entered the bar, felt yourself being swallowed up by heat and body smell and the sour mash of the alcohol and the pepper from everybody’s cigarettes, in a wham plus the thump and noise of the music. It was like entering some other absolutely consuming element: jumping into a still and warm ocean. That first moment, then accommodating yourself. Some small number of women were painters like me. Many were plus-ones—women on various arms, posing and temporary, there for generalized love of art or love for some particular and passing artist.

Painters were mostly men. The sculptors were always men. You could tell them by the stains on their jeans—acetylene for the sculptors, acrylic and glue for the painters—and by the color under the painters’ fingernails. Max’s wasn’t just a restaurant. It was a museum of unpaid tabs. And it was also a fellowship.

You’d push past Frosty Myers and John Chamberlin, up to Mickey’s face behind the bar, in a dark blue sweater, wiping out a wineglass with his long, soiled dish towel. The times I spoke with him at length did not go well. He always seemed to have his attention drifting elsewhere—somewhere above my words or to one side of the conversation, receiving signals from a calm elsewhere, until finally you stopped trying. Or someone found you and explained about Mickey and drugs, and how he was always just the same, he was like that with everybody.

Above the thumping music everyone shouted to be heard. To be appreciated, recognized, seen for a night, all of it coiling around as you sipped wine, grinned, unstuck lips from your teeth, lit a cigarette, knowing inside the inhale you were smiling. There was the overall calming feeling then: usually in life there is a right place to be.

Sometimes you find out too late. Or you never knew about it. Or this right place was inaccessible—you were not cool enough, rich enough, enough, enough. So to find yourself, on a night in Max’s in that unimpeachably right place, with the right people, at the right time: this was unspeakably soothing. It was to be without want. Without ambivalence. To know that the club owner knew you. Knew your boyfriend, your friends, your individual preferences, operated the famous club for all of us. It was an amazingly tactful and fortifying compliment, paid to us every night.

For us, Andy wasn’t an artist. He was something—a force, a figurehead, a showman.

Talk was monosyllables. Bellowed through cupped hands. You’re here! Yes! Came with Poons? Good. Come over here! How are you? Good! Thanks! You look great! No, I already have one! Everybody’s back here! What? We’re all here, we’re all back here! John Chamberlain had deep creases in his face. They crinkled whenever he laughed. He laughed a lot. I thought it was because of all the money he was making from those crushed automobile panels he turned into sculpture. Sometimes I’d sit in his red booth, across from that round, lined face, and laugh right along with him. You didn’t need to have a reason. We could smile that way for a night, looking around at the club, sawing at our steaks, filling an ashtray—and then realize later that we’d never said a word.

And then you wandered past the big central area of red booths, into the smells of dinner and the irrelevant meals floating on platters above the waitress’s shoulders, past the non-artist eaters who also came to the club. And then at the far end of the restaurant was Andy.

Warhol and his entourage holed up in Mickey’s private room, around a huge circular table. But it was their club too. That they had been drawn here by the same noisy power source we were drawn to was strange. The Factory people dressed in wild getups with exotic, creatively teased hairdos. You didn’t know if they were armed. Dan Christensen believed some of them were packing guns. And when you looked you saw this could conceivably be right. Everyone close to Warhol had become skittish after the experience with Valerie Solanas. She had ridden the Factory elevator, fishing in her handbag where she had two guns, caught sight of Andy, and squeezed off three rounds, one finding and piercing her target through his slender torso.

Sometimes at Max’s, Andy would unbutton his shirt and show the scar as if it were an old war wound. That had been only a few years before. They seemed not to know what else to expect, and there was hostility from our side: we didn’t consider the Factory people artists. Pop art was an affront and insult to the more difficult and serious thing we understood ourselves to be doing.

Some people are attracted to art for the chance to live like outlaws: outside the Monday and Friday margins, the hashmarks of nine and five. They do the minimum necessary work to qualify and really hope their lives will be the art. I hadn’t come for the oddness of the art world. It was different for me at night: then I was as restless as anybody else. But my daytime model was Matisse, who painted in a business suit.

For us, Andy wasn’t an artist. He was something—a force, a figurehead, a showman. He didn’t paint—his work was in silkscreen. He hated, he said, the act of painting. Soon we feasted on details of his former existence. How Andy had started by drawing shoes for Bonwit Teller until he realized there was quite a bit more to be made doing the exact same thing in the art world.

Then he started doing the shoes, not as ads but as silkscreens. We wondered about his cow fixation, which was apparent in an exhibition of his cow wallpaper at the Whitney. (Along with floating silver balloons.) Then we learned that his uncle had been a milkman. So there was respect and hostility. Hostility: if you are an artist, anybody else getting attention as an artist is a hazard. The amount of money and attention is limited. That anger, that sense of flat injustice in the appreciation of others, is one of the world’s first signs that you are an artist.

And there was the respect, the business acknowledgment: the pop artists had found this surprising and direct route to money. These thoughts could sometimes make Max’s feel sadder. A moment when the wheels came off and the chassis sat there and you realized the art world was a small place bounded by compromise and disappointment. It chilled you, a thought of this nature, like a wind. And you’d duck your nose into your wineglass or refill your lungs with cigarette smoke until even the backwash of that feeling went away. And after a few minutes some sensation or person distracted you, and the gray unwelcome sense was gone.

You couldn’t not be aware of him. That weird neutral presence.

Bob Dylan played Madison Square Garden, and somebody got me tickets. By chance I landed a great seat, very close and a little to one side. There was Andy, standing, leaning. His tall, almost model-thin body against the wall right near my seat. The eyes behind his glasses rested half-closed as he stared straight ahead with his deadpan, unchanging look. He was there so many of my other nights that I was not surprised to find him on an evening when I wasn’t at Max’s. His blond wig had the consistency of straw: the affect so diminished that after a while he seemed a kind of urban scarecrow.

He stood alone the whole concert. His expression never changed. Perhaps he was waiting for someone to snap a picture. You couldn’t not be aware of him. That weird neutral presence. I never found out why he was standing by my seat, who or what he had expected.

I tried to explain this to my Florida dealer, Dorothy Blau. She and Andy were tight. It was that thing, then, of Andy being around. I could tell Dorothy wasn’t exactly listening. Once I’d said his name, she was just waiting me out. She had something she wanted to say. “Oh, doll, it’s funny you should bring him up. I just heard from Andy,” she said.

“Why?” I asked. I wondered if Andy knew we shared a Florida dealer. Or if he had already mentioned to her coming out that night for Dylan and finding himself standing near me.

“So last week I go to The Factory. You know, Andy has his cosmetician waiting to take care of my makeup. Well, she does a very excellent job, such a nice job. Then he snaps two pictures of me for a silk screen.”

She waited. When I didn’t say anything fast enough, her style of waiting became a little affronted. “Did his cosmetician do your makeup wrong?” I finally asked.

“No, doll, you aren’t getting it. I had arranged for just one portrait. I thought it would be the one, a silk screen like the Jackie O. But he gets on the phone just now, all wispy and Andy and innocent: ‘Hi Dotty. Both your portraits are ready.’ Both! So he’s proposing to charge me twenty thousand for the two of them, or fourteen if I go ahead and let him down and take only one.”

I wanted to say, What a hustler. To ask, Why would Andy, with all those Factory people, need to chisel an extra six thousand dollars out of our sweet and bubbly Miami dealer?

I told her to stick to her guns. If Dorothy remembered only asking for one portrait, then buy only that one. “Doll,” I said, “be true to yourself.” I was always surprised, talking with Dorothy, that I could get away with words like “doll.” Did she really think that was a word I otherwise ever used? But people usually liked the compliment of you talking like them. Dorothy bought both, worth millions now probably. Far more than paintings by any of us in the front room who had thought of Andy as the backroom embarrassment, as our nightly inconvenience.

You’d see handsome Bob Mapplethorpe, who came with a black-haired and thin woman, Patti Smith. Their plans already incorporated the power shift we couldn’t quite feel taking place under our feet. That Andy, with his energy-free persona in the back of the restaurant, was going to dominate. Patti Smith would write later about the military campaigns she plotted with Robert: how to penetrate the defenses around Andy’s table at Max’s. How to traverse the big main room. When would be the best time to approach Andy? Which day and hour? How should Bob dress? What should Patti be wearing when that right time came?

Our tables—where the noisy group of us painters and sculptors spilled drinks and smelled that stinging cut of alcohol on the backs of our hands and tried to make ourselves heard over the din—were just the area she and Robert had to cross on their journey to Andy’s table. There was music playing. Part of the job of songs is to keep you from noticing your gathering fate. That you are aging, that you are less central than you imagine. Max’s house band—they played in his basement—was the Velvet Underground. So rising from your feet, always, the slowed-down vocals and dragging chords: “Linger on, your pale blue eyes. . . .” “Sweet Jane. . . .”

Lou Reed and Nico; their music had something. You’d walk downstairs and see shadows swaying. But when you paused upstairs and listened, that music was correct for the moment. Sad, romantic, and overripe.

The tension between the conceptual artists, the land-matter artists, and my own hands-on, abstraction painter-sculptor group could become fraught. Artists competing for something incredibly valuable and very limited. Money, attention, validation.

Robert Smithson and Carl Andre were also at the bar. Their dress code was scruffy modern—heavy denim overalls over work shirts. Clothes advertise the tone of your work: their pieces seemed to derive from a disappointed construction site. Smashed mirrors, dirt, stone, brick. Every night their lumpy bodies occupying our bar. Those encroachers. They were called only by their last names. Smithson and Andre, like partners in a detective agency.

Smithson was tall and black-haired, with skin pitted like a poorly paved road. Andre was shorter and heavyset, with a long beard and pugnacious face. Until Smithson’s death—a summer plane crash in Texas; I pictured a cactus, then the crash—the men were inseparable.

After that, death seemed to be stalking Andre. A decade later his wife plummeted out of their thirty-fourth-floor window. Andre stood trial for three years, then was found innocent. He got off. By that time Max’s was over. We were over too. There was no proper place to be with everyone to talk about Andre’s surprising release, though it would have been interesting to see the face of a man who had perhaps committed murder and had just had his freedom, surprisingly, restored to him. Mickey had closed the bar. He tried another, too far downtown. Nobody went. He died of an overdose, in bed.

As gone then as Robert Smithson and Carl Andre’s wife. All the different art groups attracted to Max’s hated each other. The tension between the conceptual artists, the land-matter artists, and my own hands-on, abstraction painter-sculptor group could become fraught. Artists competing for something incredibly valuable and very limited. Money, attention, validation. It felt like the next thing was a fight, which could erupt at any moment.

One night, I finally tried the lobster. I didn’t know what it had to do with Max or Kansas City, but it had always been there on the menu, so I ordered it. I was sitting across from Ken Greenleaf, my boyfriend. He’d been on the cover of the New York Times Magazine, representing the new sculpture. Ken’s face was shiny with grease. He was sawing at his meat with the thick-handled knives Mickey preferred. And sometimes he delicately patted his lips with the bandanna he wore around his neck.

Then he put down the knife and got quiet. The air between all the groups had become supercharged, as it does before a storm. Sounds turned strangely distinct. Silver and glasses. People’s walks became heavy-footed and exaggerated. Smithson thumped past our table in his thick boots. Ken was now quietly and roughly drying his fingers with the napkin.

It was so quick. The booted thump, and then Smithson had pulled Dan Christensen away from the bar by his shoulder and was pistoning his closed fist into Dan’s face. Dan slipped and kicked over his stool. Then Frosty Meyers was reaching around Smithson and I said, “Call someone.”

But Ken was already among the twisting men. Carl Andre wrapped his short, meaty arms around Frosty Meyers. The men stayed together, and three skinny figures darted out from Andy’s room at the back of the club. Soon ten men were spinning together on the floor, elbows thumping on the floorboards, upending barstools, sending chairs to make their rumbling, protesting noise as they skittered across the club’s floor. I remember John Chamberlin, still grinning, stepping far away from the pile. I remember Dan’s big thigh muscle showing through his jeans as he kicked Smithson twice in the side. It couldn’t have lasted more than a few minutes.

Then Mickey’s staff was pulling red-faced men apart. Dan was swollen and breathing heavily. And the tall and strange-looking men from The Factory were pulled away, looking sourly back at us. They’d never said a word. Just retreated to their own precincts. Mickey made some kind of speech—you couldn’t translate the sentences, but it was just the right calming sounds, when suddenly everything had been so present and combustible.

Ken and I stood outside with Dan Christensen. October city wind cooled our skin. Dan was swollen-faced, breathing hard. He kept smiling and letting his mouth go slack, remembering different moments as he regained control of his breathing. He was a little drunk. He grinned again. “Huh,” Dan said. “So they turned out not to be packing after all.”

“No,” Ken said.

“Don’t know why Mickey had to break it up,” Dan said. “We could’ve taken them.”

It was dark and quiet outside on Seventeenth Street. A cab and a bus streaked by. I said he was right. Dan’s breathing was now mostly in its regular rhythm.

“Yeah, we took them,” he decided.

“Yeah, let’s go back in,” Ken agreed.

__________________________________

From Brightening Glance by Pat Lipsky, published by the University of Iowa Press. Copyright © 2025 by Pat Lipsky.

Pat Lipsky

Pat Lipsky is a painter and writer. Her art has been exhibited in the André Emmerich Gallery and the Eric Firestone Gallery, among others, and is currently represented by James Fuentes. Her writing appears in Tablet, The New Criterion, The East Hampton Star, The Awl, and Public Books. She lives in Chelsea, New York.