A New Autobiography: On Re-Envisioning Gertrude Stein’s Classic Cover

Lana Lin Asks Us to Reconsider Our Expectations of Memoir, Art and the Creative Process

During the pre-vaccine summer of 2020, I sat behind a long wooden table that my partner, H. Lan Thao Lam, had recently installed for me across from the fireplace in a former sawmill to which we had escaped from the COVID pandemic, and stared out through the open Dutch door. I was reading a fascinating article by Corinne Anderson, “I Am Not Who ‘I’ Pretend to Be: The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and its Photographic Frontispiece.”

I was in the midst of writing The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam, styled on Gertrude Stein’s conceit of writing The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas in the voice of her life partner. Combining memoir, social criticism, and conceptual art, my book tells the queer love story of a former South Vietnamese refugee and a Taiwanese American suburbanite who find a home with one another against the backdrop of war, illness, and the everyday slights of racism and gender oppression.

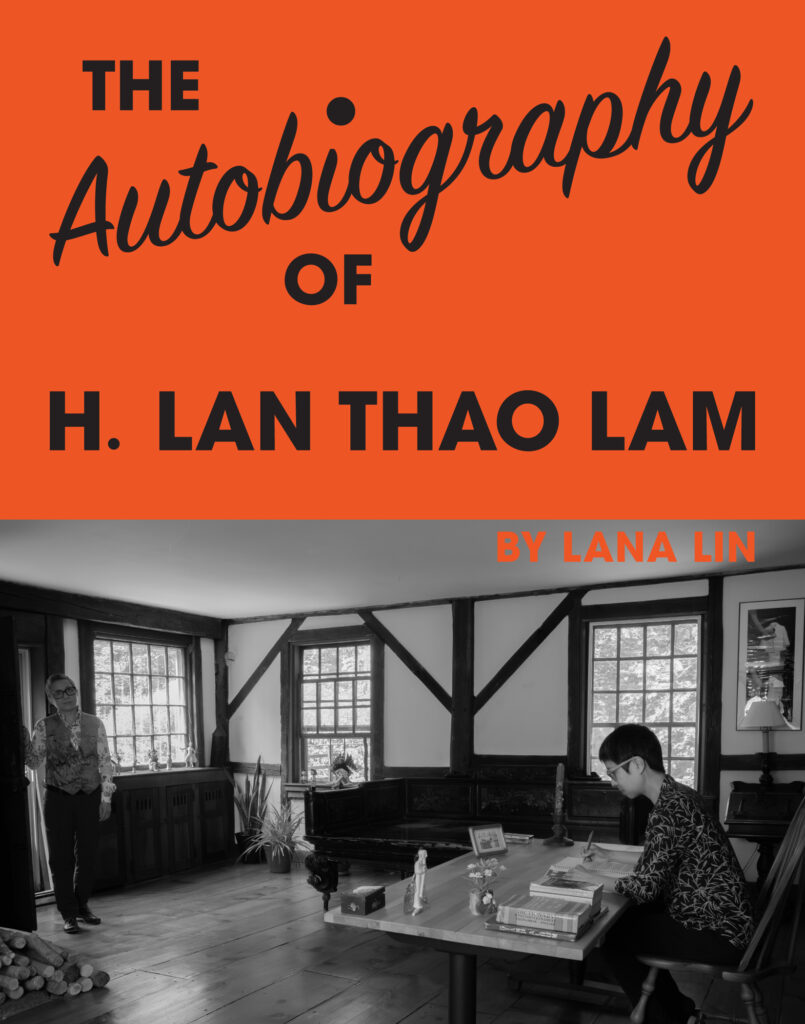

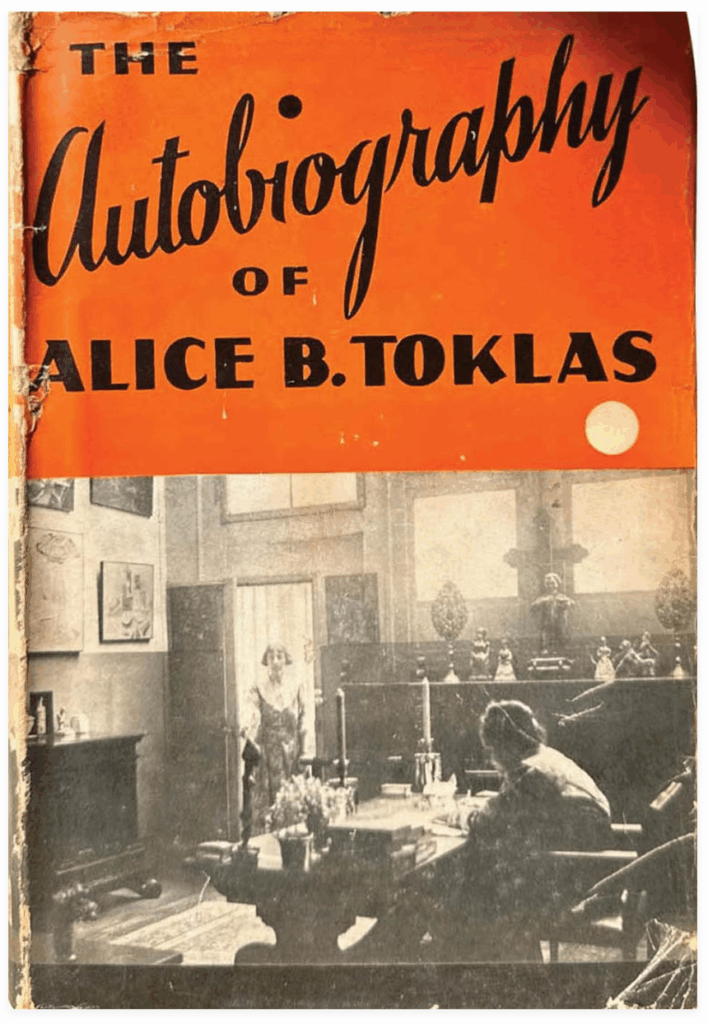

Andersen’s article describes Man Ray’s frontispiece, which also appears on the dustjacket of the 1933 first edition published by Harcourt, Brace, and Company, as The Autobiography en abyme. In a footnote, she clarifies: “Man Ray’s photograph reproduces in miniature the structure of The Autobiography.” Immediately I visualized my book cover image performing the same function.

I have used both autobiography and photography as forms of simultaneous self-revelation and self-alienation.

As writer, filmmaker, and as part of the collaborative artist team ‘Lin + Lam,’ I and we often refer to history to offer a critical re-reading. For a mixed media installation and 16mm film, we re-enacted 1960s South Vietnamese propaganda films, Lan Thao performing in drag as Former President of the Republic of Vietnam Ngo Dinh Diem and his wife Madame Nhu. We have replicated Edmund Engelman’s 1938 photographic documentation of Freud’s home and office at Berggasse 19 taken on the eve of the psychoanalyst’s exile from Vienna.

And in 2018 I staged a cinematic recitation of Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, guided by Lorde’s longtime friend Adrienne Rich’s concept of “re-vision,” which Rich defines as “the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction.” Lin + Lam’s re-visioning of Man Ray’s photograph and my re-visiting of Stein’s text follows along these same lines.

As I studied Man Ray’s photograph of Gertrude Stein at her desk and Alice B. Toklas at the door about to enter the hallowed studio at 27 Rue de Fleurus, I was gripped by an uncanny sense of recognition, although the similarities between Stein and Toklas’s Paris apartment and my Connecticut address are superficial. I was seated behind an imposing desk and could easily imagine Lan Thao entering through the Dutch door just as Alice did. Three window panes dominate the wall behind Alice and Gertrude. So, too, would they in Lan Thao and my photograph of “our mill.”

Gertrude sits with a stack of books to her left. I gathered Lan Thao’s stamp album, Vietnamese English Dictionary, and the Vintage Books edition of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas with a cover photograph of Gertrude Stein by Carl Van Vechten, which are visible on the table to my left in our photograph. Lan Thao and I chose meaningful objects to be memorialized in this document of our domestic quarters: a framed photograph of Lan Thao as a child posing in front of a treasured credenza and a wooden box with ivory inlaid carving, both from Saigon. The image contains a private universe of symbols, our own mythology of characters.

Where what appears to be an African statue guarding over Stein’s desk, we set a sculptural component of our collaborative art project which amalgamates idols derived from Freud’s antiquity collection with Transformer toy parts. On my table balances a Sculpey clay figurine of the Egyptian deity Ptah mashed with Unicron, whose wings serve the dual purpose of cape and sculpture brace. Totems of Lan Thao’s and my relationship are propped on the window sill: a hand puppet of the King of the Gods and plastic effigies of Marcie and Peppermint Patty, the faithful Peanuts pair.

We consulted Maira Kalman’s illustration of Ray’s photograph for The Autobiography of Alice T. Toklas Illustrated, reissued by Penguin Random House in 2020, which pruned the detail laden photograph to its essentials. She reduced the two candles on Stein’s desk to one, which we, in turn, copied.

Danielle Dutton, who designs all the books for Dorothy, a publishing project, carried forward our intention. Taking a cue from our photograph, she designed the cover of The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam as an homage to the 1933 first edition of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

The book cover and photograph do not aim for a facsimile, nor does my manuscript. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is really the autobiography, if it is anyone’s autobiography at all, of Gertrude Stein, written by Stein ventriloquizing Alice’s elocution. The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao is more genuinely a double autobiography, if it is anyone’s autobiography at all, as the chapters are divided more equally between Lan Thao’s and my stories, and I do not feign Lan Thao’s voice.

In Camera Lucida, Barthes reflects upon the paradoxical distancing effect of photography, a medium characterized by its presumed indexical relationship to reality: “[T]he Photograph is the advent of myself as other: a cunning dissociation of consciousness from identity.” Similar to photography, autobiography holds a privileged relation to the illusion of reality. I have used both autobiography and photography as forms of simultaneous self-revelation and self-alienation. Adapting Audre Lorde’s term “biomythography,” which she coins as a blend of biography, mythology, and history in her 1982 Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, I categorize my book as “autobiomythography” to more explicitly name the self in a complex interplay of self/other/life/myth/history/writing. The cover art for The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam could also be considered “autobiomythography” as Lin + Lam produce a mythic version of their domestic life, quoting Ray’s representation of Stein and Toklas’s performative scene.

While my book is attributed to a single author, the question of authorship remains: what does it mean to author a life?

Though unaccounted for in the frontispiece’s caption, “Alice B. Toklas at the door, photograph by Man Ray,” Stein is a co-conspirator in the ruse of the photograph. There is no caption for my book’s cover art. The question might then arise as to who photographed the image. No “one” is taking the image. Just as in the text the “I” is rendered unstable, here “the eye” appears to be neither Lan Thao nor me. The ambiguity of authorship is meant to unsettle the reading of the text. While my book is attributed to a single author, the question of authorship remains: what does it mean to author a life? Can a single individual have complete autonomy over their life? Are we not plural, collaborative, and permeable from the outset?

If Gertrude Stein seeks to anonymize herself, in my book’s cover art and text, I make a claim for recognition. The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam adopts Stein’s device to reflect on the distance between then and now, the difference between those who came before and those who stand in the room with me. Staging my book and its cover art in reference to an iconic portrait of closeted Jewish lesbian expatriates in the mid 19th and first quarter of the 20th century indicates by inference the invisibility of Asians as authors of their own experience in Europe at that time, but more significantly, it assembles the everyday activities and sentiments of two Asian queers in North America into the making of history.

In A Map to the Door of No Return, Dionne Brand writes: “One enters a room and history follows; one enters a room and history precedes.” Brand understands that human history is contingent upon who is positioned at the door. In 1922, Alice B. Toklas stood at the doorway. I willed Lan Thao to take their place.

When Lan Thao and I collaborate, we talk incessantly about history and context. In trying to meet restrictive word counts for grant applications, I have been known to protest, “Do we really need to go into all that history and context?” Lan Thao has staunchly retorted that the H. of their full name stands for History. In 2020, Lan Thao opened the door, poised to enter and sit in the room with History.

Cover design by Danielle Dutton. Photograph by Lin + Lam.

Photograph by Man Ray.

__________________________________

The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam by Lana Lin is available from Dorothy, a publishing project.

Lana Lin

Lana Lin is a writer, artist, and filmmaker based in New York and Connecticut. She is the author of the book Freud’s Jaw and Other Lost Objects: Fractured Subjectivity in the Face of Cancer and film and video works including The Cancer Journals Revisited. Her various works and collaborative projects (with Lan Thao Lam as “Lin + Lam”) have exhibited at festivals and art and educational spaces throughout the world, including the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum, and New Museum, New York; The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Gasworks, London; the Taiwan International Documentary Festival and Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute, New Taipei City; Arko Art Center, Korean Arts Council, Seoul; and the 2018 Busan Biennale. Having had three years of psychoanalytic training before dropping out, she sometimes still dreams of becoming a psychoanalyst one day. The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam was longlisted for the 2025 National Book Award.