A Name on a Line: Chrysta Bilton Tells the Story of Her Birth

With an Extremely Brief Appearance by Her Father

I was three weeks late, and there was no sign that I’d come out anytime soon. My aunt Diane, younger than my mom by five years, was terrified—not because of any potential health risks, but because, as the days wore on, it was becoming increasingly likely that I was going to be born a Scorpio (which Diane’s ex-girlfriend had been) rather than a Libra (which Diane believed was the best sign because that was her sign), and so something had to be done. Rather than leave this all to fate, Aunt Diane had decided to take matters into her own hands by dragging my mother on a hike to the top of Franklin Canyon, behind the Beverly Hills Hotel, in hopes of inducing her labor. Diane had only thirty-six hours before the stars changed to Scorpio.

“I can’t go any further!” my mother complained as she held on to her pregnant belly with one hand and her bright orange Christian Dior parasol, which she was using to try to block out the rays of the crisp October sun, with the other.

“Just keep walking,” Diane instructed between breaths, half pushing her sister along the trail, half dragging her own self up.

Debra and Diane were a strange breed of sister. They were all they had left of their family and they loved each other deeply, but there was constant jockeying for control.

Twenty minutes into their hike, the plan worked. Suddenly, halfway up the hill, Debra felt the most intense pain of her life.

“It’s happening, Diane! I just had a contraction!” The two smiled with excitement until Debra felt the pain course through her body once more and screamed, “Oh my God! We have to get to the hospital—now!”

Diane clearly hadn’t thought this through. Getting her sister up the hill while not in labor was a hell of a lot easier than getting her down while Debra was experiencing the intense undulations that now overwhelmed every part of her body every few minutes. For anyone else in the canyons that day, it must have sounded like an animal had been caught in a trap. Debra screamed the entire way down the hill and into her Jaguar, and the two sisters raced off to Cedars-Sinai, the waves of horrific pain increasing with every speed bump and L.A. traffic light.

“Drugs! I need drugs!” Debra yelled as a nurse wheeled her into the birthing room. Drugs, though, were not part of the plan.

“They’re on the way!” Diane assured Debra, seemingly enjoying watching her sister in extreme pain. “The nurse said just a few minutes!”

In truth, Diane had not ordered any meds from the nurse and was committed to sticking with Debra’s original plan, which involved just breathing and walking around the hospital room doing squats.

Debra had spent half of her pregnancy practicing this moment in her weekly Lamaze classes. She was haunted by all the horrors she and Diane had experienced growing up, starting in the birthing room, and determined not to repeat them for another generation. Back in 1949, when their mother, Bicki, was nine months pregnant with Debra, Bicki fell out of the car on the way to get ice cream (there were no seat belts in cars back then), causing her to go into early labor. Debra was born breech with a broken collarbone and then placed in an incubator for two days before she was ever held by her mother. It was a jarring way to enter the world, and Debra often wondered how much this experience colored the rest of her life.

When Diane was born, their father, John, was so hopeful he would finally get a boy that when he saw her for the first time—a girl with a giant red birthmark all over her face—he found his new daughter so ugly that he was said to have vomited all over the hospital floor. Diane’s “strawberry” disappeared after a few months, but it was clear that her father never loved her the way he loved Debra.

To make matters worse for both sisters, Bicki had been put under the drugged spell of twilight sleep, a common procedure in the 1940s and ’50s; it had left her awake enough to feel pain but asleep enough not to have the faintest memory of having given birth to her children. It goes without saying that Bicki did not go on to breastfeed. She was not a cozy-fuzzy mother. Debra spent her early months alone in a hospital, and she returned not to her mother’s warm arms but to the hands of a nanny.

Perhaps to heal their own early wounds as much as to give me a different life, my mother and Aunt Diane had been determined that Debra stay awake—that she feel, and experience, and remember every second of giving birth to me. Then the excruciating reality of labor came up against the dreamy fantasy of a natural childbirth, and for Debra all bets were off.

For twenty-six long, miserable hours, Diane continued to assure Debra that the epidural was on its way, but it never came. (Diane did try to appease my mother with a boom box blasting Marvin Gaye and Al Green.)

As morning turned to afternoon on a chilly, golden October day, the birthing room slowly filled up with a large group of women dressed in early-eighties-era high-waisted blue jeans; ironed, tucked-in button-down shirts; chunky jewelry; and oversized blazers. This was in stark contrast to what was going on in the neighboring rooms, where more “normal-looking” couples—yuppie husbands and doting housewives—ere delivering children.

When it finally came time for active labor and as Debra’s pain became more unbearable than anything she’d ever experienced in her life, she had a full-fledged panic attack. She was suddenly unsure if she was equipped to become a mother after all.

“Wait, no, I’m not ready! Put her back in!” she screamed.

“Sorry, Debra, it’s happening,” the doctor said. “Now push!”

Debra’s sweat-drenched hand squeezed Diane’s as she pushed… and screamed… until… finally… there I came…into her arms. All ten pounds of me. My mother looked down at my face, trying to get a glimpse of my smushed eyes through rolls of baby fat. I wasn’t the cutest baby, but to my mother I was the most beautiful child she had ever seen—half her, and half Jeffrey. She kissed my head and held me close as I instinctively found my way to her breast, and she was overcome by a rush of dopamine and love and awe that far surpassed any drug she’d ever taken.

“We did it, Deb,” Diane said as she bent down to kiss my head. “She’s a Libra. A few more hours and she’d have been a Scorpio.”

My mother looked down at me, held my little finger, and whispered, “My little treasure. This is the beginning of a great love affair.”

The following morning, as Diane and Annie returned and more friends started arriving with flowers and baby presents, a nurse entered the room and handed Debra a birth certificate to fill in. Debra took the pen with a smile and, in her giant, larger-than-life handwriting, carefully spelled out my name: Chrysta Carolyn Holmes Olson. There was never any question that I would get my mother’s last name. She felt pride knowing that her father’s line of governors and judges and suffragettes would be carried on for another generation. Chrysta had been Jeffrey’s idea. He had seen the name signed in the corner of a painting in an art gallery and called Debra from a pay phone to suggest it. Debra ran the numbers with a numerologist, as one does, and after replacing the i with a y on the woman’s suggestion, it was settled. Carolyn, my first middle name, was an ode to Debra’s mother’s side of the family, after her favorite aunt, an artistic woman who, according to family lore, had stood up from her deathbed, walked over to the piano, and played one verse of “Moon River” before passing away. Holmes, my second middle name, was taken from the man Debra believed to be Jeffrey’s great-uncle, Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Debra moved down the document to sign her name above the line that requested the mother’s signature. Then she realized she had a problem, as she was unsure what to do above the line that asked for the father’s signature. For what seemed like an eternity, her pen just hovered there.

The nurse stood over Debra, peering up at the clock across the room, getting visibly impatient as my mother gripped the pen in her hand.

“You know, the father can’t make it today,” Debra finally said nervously as she looked at the nurse. “He’s at work. I will just sign the line for him.”

The nurse’s hand came down to stop her. “I’m sorry, but the father has to be physically present.”

Diane was sitting nearby, watching.

My mother looked back at that word: “father.” It was such a short, simple word. A wave of intense emotions pulsed through her. She thought about her own father, the look of pride and amusement on his face whenever she’d show up at his courtroom, a blond, wild teenager interrupting an important case as she waved a speeding ticket in the air with a grin, wanting his help getting her out of it, and then she thought about how much she missed him. Her heart broke at the thought that John would never meet this beautiful baby lying next to her, and that I, in turn, would never get to know him, the man who had meant more to her than anyone.

The single most important relationship in her life had been the one she shared with her father. She looked down at me, this beautiful child asleep in her arms, and couldn’t breathe at the idea that she might be harming me by depriving me of a father figure.The excitement of my birth momentarily gave way to sadder memories: the cold fact that except for Diane, every single person in her family was dead—all of them from the dark curse of addiction, which just made it worse, because there was always the lingering feeling that she could have done something to save them. Then an even more horrible thought occurred to Debra. The single most important relationship in her life had been the one she shared with her father. She looked down at me, this beautiful child asleep in her arms, and couldn’t breathe at the idea that she might be harming me by depriving me of a father figure. That this child’s father would be just an empty blank line—a black hole where a glowing star was meant to be.

“Can you please hand me a phone?” Debra said to the nurse, who was still standing there impatiently.

“Debra, what are you doing?” Diane asked, lunging to get to the telephone as quickly as she could as soon as she saw that her sister had that familiar look of I’ve-got-a-plan-and-it’s-probably-not-a-good-idea-but-just-try-to-stop-me written all over her face.

“I’m calling Jeffrey to come sign the birth certificate,” Debra said, grabbing the phone from the nurse before Diane could get to it.

“Honey, I don’t think that’s a good idea,” Diane said, now attempting to grab the phone from her sister.

But it was too late. Debra held the receiver tightly in her hands, shoving Diane off, and she started dialing.

“Jeff, I need you to come to the hospital to sign Chrysta’s birth certificate.”

“I don’t have a car,” Jeffrey said—he was likely stoned, or sleeping, or both—as he registered that it was Debra on the phone and what she was asking. “I don’t even know how to get over there.”

“I’ll get you a taxi,” Debra said, defiant. “Jeff, you can’t just be completely anonymous.” He paused for a moment, and Debra could tell he was teetering his way out. “Please come. I’m begging you. Just to sign the birth certificate—that’s it. You don’t have to do anything after that—I promise. You don’t have to see her ever again. She’s going to need this—psychologically. Otherwise you will just be this big blank space in her life. Please. I’ll pay you for it.”

Jeffrey showed up at the hospital a few hours later and was so far out of his element that he himself looked like he needed a stretcher. He was wearing sunglasses, which he refused to remove, and a tattered boater hat, which did not hide his face as much as he would have liked it to. Debra’s gang of women had returned by then, bringing food and drink and merriment. It was probably the first time in his life that Jeffrey had been in a room full of women who could care less about his good looks.

Awkwardly, Jeffrey followed Debra’s instructions to hold out his arms as she placed me into them.

“She looks like you, doesn’t she?” Debra asked, eyes twinkling at the sight of my father holding me.

He gave me a few uncomfortable pats on the back and then returned me to my mother’s arms as quickly as he could, as if this were a game of hot potato. As Debra watched Jeffrey hold me, however briefly and uneasily, she was flooded with a sudden, intense connection with him that she herself did not understand.

All he could think about in that very moment was, “What’s the fastest way out the door?”Jeffrey, on the other hand, just cringed. He looked around at all the eyes on him, at all these lesbians intently watching for his reaction. He imagined they all anticipated that he would take one look at the child and say “Oh my God, this is my baby!” with an adoring gaze, which was the exact opposite of how he felt. All he could think about in that very moment was, “What’s the fastest way out the door?”

In truth, the other women were judging not Jeffrey but Debra. As she looked at Jeffrey, they looked at her, none of them capable of understanding why Debra had brought this man here. Chief among them was Aunt Diane, who identified as a radical feminist and fought the patriarchy and all forms of male dominion and oppression. She hated men and didn’t understand why her sister was so hung up on the role of a father in this child’s life. She looked at Jeffrey, this oddball in his stupid hat and sunglasses, and just shook her head in disapproval.

Debra reached over and handed Jeffrey the birth certificate and a pen. Jeffrey glanced down to where the blank line was. He didn’t want to do this; he felt he was being pressured into more than he’d signed up for. But some part of him also felt for me, and so, with the flick of his wrist, Jeffrey signed his name, then handed the paper back to Debra and left the hospital as quickly as he had come in.

______________________________________

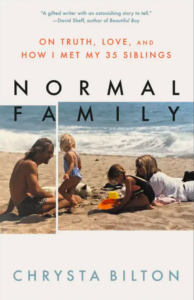

Excerpted from Normal Family: On Truth, Love, and How I Met My 35 Siblings. Used with the permission of the publisher, Little, Brown. © 2022 by Chrysta Bilton.