A Look Inside the 17th-Century Witch Trials of the Arctic Circle

Chelsea Iversen Asks: What If Northern Norway’s Accused Witches Fought Back?

Finnmark is a quiet, unassuming sprawl of natural splendor situated in the northeastern corner of Norway. It’s well within the Arctic Circle, seeming to head off the Barents Sea, sort of the last stop before ice bridges and polar bears and perpetual winter. In Finnmark, the villages have always been small and sporadic and isolated, and the relationship with the natural world has always been immediate. Storms and seasons were everything. Fishing was—still is—the most crucial industry.

And the region has a storied history with witches.

The seventeenth century brought witch fever all the way up to this arctic region known for its codfish. Roughly 137 people were accused of Trolldom (witchcraft) in a span of less than one-hundred years. Of those accused, 92 were either killed by execution or died while in custody. This may not sound like a high number—after all, about 12,000 people were executed across Europe during the witch hunt years. But in a region where the population was only about 3,200 at the time, this meant that almost five percent were accused of witchcraft.

Hunting witches defined almost an entire century for the coastal communities of Finnmark.

What can we learn from the fate of the witches of Finnmark?

There are surviving court records from the seventeenth century that document the accused from these trials and their crimes as well as their confessions and executions. These records and the scholarship that has analyzed them make for jaw-dropping reading. There are, for instance, accounts of women confessing to drinking beer with Satan and of seeing neighbors and friends turn into cats and ravens. It truly is the stuff of fantasy.

Though the trials themselves often only focused on one witch at a time, there were several instances when more than ten people were killed in a chain of accusations. It happened like this: once one person was accused, it was common for her to denounce others who may have been involved in witchcraft, in her village or in neighboring ones. Grudges and suspicion fueled the witch craze, and according to the laws at the time, one accusation was enough to send someone to trial, to inflict torture and ultimately, execute them.

Unsurprisingly, 81 percent of people who were killed for witchcraft during this 100-year span were women. Norwegian women made up most of these deaths, but indigenous populations of Sami suffered right alongside them. Some of the indigenous traditions that Sami men and women practiced, like the use of rune drums, for instance, were considered to be some form of sorcery or witchcraft by the Norwegian authorities at the time, which likely meant that any Sami people living amidst Norwegian communities had to hide or stop many traditional beliefs and practices, lest they be accused and killed for it. Of those Sami men who were accused of sorcery, a few did not even make it to their sentencing because they were murdered while in custody.

There are plenty of theories today about what could have caused such an uproar over witchcraft during this time period. Some blame ergot, a fungal contamination of wheat and barley that caused hallucinations and appeared to have some kind of witchcraft behind it. Other scholars believe that the harsh environment of the Arctic and the dependence on weather caused witch paranoia, which was already rampant in other parts of Europe, to heighten. Others blame Christianity and religious clerics trying to stamp out any lingering paganism. And, of course, there are theories that claim witch trials happened because of good old-fashioned misogyny and bigotry.

Most likely, it is a combination of all of the above.

Much of Europe has been plagued by witch trials at some point. To go all the way back in time and start analyzing the why, I would point to the 15th century treatise on witchcraft, Malleus Maleficarum or The Witch Hammer, written by a Catholic Inquisitor. This treatise explained who in the community were most likely to be witches (women), how to find those witches, and what lawmakers and neighbors should do when they were discovered. This text explained that women were more susceptible to the temptations of the devil because they were the weaker sex—a claim that formed (or perhaps only confirmed) the foundation of misogyny pervasive in almost all European (and American) witch trials.

It’s my hope that reading about it as fiction can help us understand why people do horrible things.

A few centuries after Malleus Maleficarum, in 1617, Christian IV of Denmark and Norway issued a royal ordinance that condemned witchcraft, which seemed to intensify witch fever within his kingdom. From 1600 to 1692, witchcraft panic swept eastern Finnmark, focused in the towns of Vardø and Vadsø, but in other surrounding villages as well. Basically, this decree criminalized being a witch, and the result was pandemonium as Norwegians rooted out so-called witches from within their own communities.

A quick word on the absurdity of torture: Accused women would often denounce friends, neighbors, and acquaintances as witches. Why? The most conceivable explanation is, of course, torture. Women accused of witchcraft were arrested and usually tortured, forced into making outrageous claims that they had made some kind of pact with the devil. These women were tortured into admitting that they’d lain with the devil or turned into ravens to fly to an evil mountain to drink beer with other witches. The details were indeed weird, but these confessions were taken as truth.

The torture mechanisms aren’t explained well in the court documents, but according to Liv Helene Willumsen, a Norwegian scholar who has written widely on this topic, confessions were necessary for convictions. This would explain why there was such a focus on getting confessions from the accused, and of course, the only way to get such outlandish confessions was to use torture to procure them. For an in-depth analysis of the actual court records that remain and all their details, I highly recommend reading Willumsen’s research.

So what do we do with these horrifying facts? What can we learn from the fate of the witches of Finnmark? Exploring histories like this one—the kind of history we think we know already but really don’t—sheds light on struggles with power that are still prevalent today.

I wanted to bring this history—a history that showcases the worst of humanity—to the imagined world of a novel. It’s my hope that reading about it as fiction can help us understand why people do horrible things and what it may have felt like to be one of the faceless, nameless victims of such atrocities. I also wanted to give the gift of magic to the characters—allowing us to imagine great power where historically there was very little.

So I asked: What would it look like if witches truly existed and had not just been pawns for a broader agenda? Would they have fought back?

__________________________________

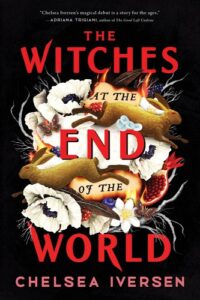

The Witches at the End of the World by Chelsea Iversen is available from Sourcebooks.

Chelsea Iversen

Chelsea Iversen has been reading and writing stories since before she knew what verbs were. She loves tea and trees and travel and reads her runes at every full moon. Chelsea lives with her husband and Pepper the dog in Colorado. The Witches at the End of the World is her debut novel.