Louise Kennedy on Discovering Fiction’s Complex Emotional Truths

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of The End of the World is a Cul de Sac

Louise Kennedy says she came to writing in her late forties, after thirty years as a chef. “I began writing by accident, when a friend bundled me into her car and made me join a writing group,” she explains during our email exchange between Sonoma County and Sligo. “At the first meeting, the facilitator asked each of why we were there, and it quickly became clear I was the only person at the table not involved in some form of creative practice; I had been a chef for many years and did not think that counted. I realize now I was wrong.” How has working as a chef influenced her fiction writing?

“Working in kitchens taught me discipline and trained me to turn up at all hours whether I felt inclined or not…to just bloody get on with it. Also, kitchens are a highly sensory environment, one in which all the senses are engaged at once, not just taste. Chefs know by the change in sound from a pan behind them that a steak needs attention, they know by touch when it is ready. This has served me well, I think, perhaps sharpening my descriptive abilities, and hopefully allowing the reader to experience my work in a visceral way.” Her acute sensory details, as well as her nuanced awareness of Irish culture and the ambiguities of relationships, are abundant in The End of the World Is a Cul de Sac.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How was your life—your writing (this collection and other projects), your family—affected by the pandemic?

I think this need to categorize, comes from having had to navigate a world in which I was not welcome.Louise Kennedy: My father-in-law died in hospital (not from the virus) in March 2020, the day before Ireland entered its first lockdown. His funeral was heart-scalding, eight of us standing what felt like miles apart in a draughty crematorium, weeping. The following weeks were a strange and frightening frenzy of doom-scrolling, manic cleaning and bickering with my children over handwashing. With the libraries and bookshops shut I had nothing to read, so friends left bags of books on my doorstep.

I moved into the spare room and powered through seventeen novels in three weeks, which somehow calmed me; I was ready to go back to work. I barricaded myself into the shed in the garden and added three stories to the original twelve in The End of the World is A Cul de Sac, brought my novel Trespasses on by several drafts and completed a PhD. It was awful not to see friends and family, and to see the effects of lockdown on my then-teenage children, but I also loved being at home gardening, cooking and writing. Part of me would love to be locked down again.

JC: Your story “Hunter-Gatherers,” which is set in the northwest of Ireland and spins around a Yeats story about a “mysterious hare” that leads a hunter astray, is one of the first short stories you wrote. The focus is on a disconnect between the narrator, a “Townie,” and her boyfriend, whose raw connection to the land repulses her.

In “What the Birds Heard,” an artist who has left her husband and plans to spend a winter in a gentrified cottage in coastal Inishowen, has a brief liaison with a fifty-ish workman who understands the ocean, the estuary, the tides and the birds. What draws you to this recurring theme of class divisions and urban/rural settings?

LK: My fixation with these differences and divisions undoubtedly comes from my always having been an outsider. In fact, I have been aware of the nuances of class since I was a small child. My family, although aspiring to be middle class, was Catholic in a majority Protestant state, and could therefore never really rise in status. When we moved to a country town south of the border, it took me a while to understand that the townfolk looked down on farmers and “bogmen.” I had believed that poverty was an urban phenomenon but was shocked at the extent of rural deprivation.

JC: I’m curious about the title story in this collection. Sarah, known as “the gangster’s moll from down the hill,” has been deserted by her husband, dead-ended in a cul de sac in the “ghost estate” he developed, easy prey for a predator in the area. What inspired the story? How did you name it? Why did you make it the title story?

LK: There is no dominant style of home in Ireland, and during the foolish years of the “Celtic Tiger,” houses that would befit a Bond villain began to pop up, sitting incongruously amidst 1970s bungalows and traditional cottages. Then the country careered into the economic catastrophe the Irish government hilariously dubbed “the downturn.”

In its wake it left a landscape blighted by half-built apartment blocks and the unfinished housing developments we called “ghost estates.” The airwaves and newspapers abounded with stories of ruin—bankruptcy, evictions, suicides—and reports of escalating drug use. I do not recall deciding to put a donkey in that showhouse, but it is possible that subconsciously I was employing a symbol of an older, more innocent Ireland —from the days before we got carried away with ourselves—to shit all over our greed and materialism.

The title came from a question my sister asked as a spacey five-year old: “Is the end of the world a cul de sac?” Initially, the collection was to be called Hunter-gatherers, but my lovely agent, Eleanor Birne, thought The End of the World Is a Cul de Sac was rather more memorable. I think she was right.

JC: Several stories in this collection—“In Silhouette,” in which a woman is haunted for decades by her older brother’s role in a murder, and “Sparing the Heather,” about the whereabouts of the body of one of the “disappeared,” buried in a secret location—are haunted by the Troubles. How have your life and your writing been influenced by the Troubles?

LK: It was not until I began to write that I understood the extent to which growing up in the north of Ireland had affected me. In 1971, when I was four, my grandmother was critically injured in a bomb explosion. After bomb attacks on our pub in 1973 and 1974, my family sold up and most of them moved south. These events were certainly trauma-inducing, but day to day life—the anxiety, the hyper-vigilance…the systemic and casual sectarianism, were at least as difficult.

We left the north when I was twelve, and my early years are therefore in stark relief against my life since. My background also affected my relationship with language. Growing up, my speech was peppered with words I now know are Ulster-Scots; when we moved south, I was surrounded by people who use Hiberno-English. And I am told I pay a lot of attention to details, to naming things. I think this need to categorize, comes from having had to navigate a world in which I was not welcome.

Rarely is everything terrible in life. Sometimes we are in heaven and hell simultaneously.JC: Another story that intrigues me is “Gibraltar,” a story told through a series of photographs, dated out of chronological order—starting in 1983, jumping forward into 2016, ending in 1973, glimpses in the life of Audrey McGuigan, nee Lynch. What led you to the shape of this story? How long did it take order the sections?

LK: A few years ago I reread Ryszard Kapuscinski’s Shah of Shahs, his book about the fall of the house of Pahlavi and the unfolding Islamic Revolution. In a chapter entitled “Daguerreotypes,” the author describes what is in a series of photographs, several of which are unseen. I wondered what it would be like to tell the story of a family through a set of photographs. I wrote a series of vignettes, and tried to use an omniscient narrator, which was very difficult.

But I persisted, applying discipline. The photographs had to appear to be random yet needed to follow a narrative arc. Arranging took months but got easier when I decided that the photographs were taken from Audrey’s funeral montage. It is the only one of my short stories that is conceptual in origin.

JC: How long did it take you to decide the order of the stories in this collection? How did you go about it?

LK: Declan Meade, the editor of The Stinging Fly, gave me some advice. He has published several collections of short stories by Irish writers and suggested I do it “the Kevin Barry way.” “Blow their minds with the first three, put anything experimental or weird in the middle, and finish on a high note.” I am not sure that “Garland Sunday” constitutes a high note, but there is acceptance, which is often all we can manage in life. And a bit of sex. Which I suppose is positive!

JC: You weave Irish folklore into many of these stories, including the final one, in which a wife prepares a bilberry cake, following a tradition in which a girl presents a special cake to the boy of her choosing on Garland Sunday. This, despite knowing her husband has turned away from her.

LK: Many of the feast days and festivals celebrated in Ireland have their origins in pre-Christian times. In rural places, these tend to be closest to the ancient ways, possibly because the land is relatively untouched and still carries the marks of those who moved over it before, and the traditions are less diluted. I guess I think writing place is a form of deep-mapping; the closer you look, the more it reveals to you.

When I looked at the Caves of Keash where “Garland Sunday” is set, I found that mythology and folklore involving stolen children, infanticide and monstrous women were associated with the area. In my story, the wife, an outsider, bakes the cake almost as an apology to her husband, a local man committed to tradition, who has rejected her after an abortion he initially agreed to. Then the wife learns of a woman a generation earlier who faced an unwanted pregnancy but had no choices available to her.

JC: You write of troubled marriages, misunderstandings, complicated relationships between family members, betrayals and memories thereof. And yet, this collection carries a lightness of being. How do you make that happen?

LK: I did not plan this short story collection. An idea would come to me, often something slight, almost elusive, and I would footer with it until I felt I had reached some emotional truth. After a while I had a dozen stories. Something happened when I put them together, I began to see connections and themes. I am told there is darkness, but also humor, so perhaps that has helped lighten them. Rarely is everything terrible in life. Sometimes we are in heaven and hell simultaneously… a woman can be betrayed by a wandering husband yet still find joy in her baby’s smile.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

LK: I am working on a novel which features a character from my short story “Belladonna.” It is about a lonely teenage girl who misunderstands the adult relationships around her and wreaks havoc. In my novel, we meet her later in life, in London and Dublin, continuing to make mistakes. I am finding it a delight and a challenge to age her and put adult problems in her path.

__________________________________

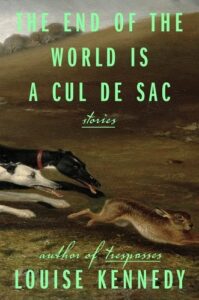

The End of the World Is a Cul de Sac by Louise Kennedy is available from Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.