A History of Gaps: Who Can Tell the Story of the Vietnamese Diaspora?

Kim-Anh Schreiber on Inhabiting a Territory Defined by Loss

I have been reacquainted with April’s habits of cruelty. In Chicago as the weather thaws I am extending the isolation that winter brings, in the most grotesque way, as tulips break from their soil and announce the arrival of spring. It’s only spring-like in the sense that spring is strangely violent. Being at home all day, moving from room to room, feels like a kind of exile, a prolonged drift in an extended present, watching a terrifying world from against the window and inward into myself.

In the midst of everything, April 30th will mark the 45th anniversary of my family’s exile from Vietnam in 1975. Having spent the past few years following its long wake, drifting from room to room which so often feels like the process of writing a book, it feels appropriate that I should be writing this essay at the culmination of this project, which coincides with the violence of a virus that can only be offset by stillness, by staying inside. I have spent weeks staring at the ceiling, or at a screen, against which these two dramas converge.

*

In her book The Senses Still, C. Nadia Seremetakis writes of the rodhákino, a peach that she had tasted in her childhood and could no longer find as an adult. She and her friends travel in search of “our peach,” finding peach-hybrids that bear characteristics of it, but are not it. These new peaches, they come to believe, are tasteless in comparison, but then, she observes, “nothing tastes as good as the past.”

Eventually, she discovers, the relentless search for the rodhákino becomes less about its rediscovery and more about the story of its loss. She writes, “In the presence of all those “peaches,” the absent peach became narrative. … My naming of its absence had resurrected observations, commentaries, stories, some of which encapsulated whole epochs marked by their own sensibilities. … The younger generation, whenever present, heard these stories as if listening to a captivating fairy tale. For me the peach had been both eaten and remembered, but for the younger generation it was now digested through memory and language.” For the younger generation, the peach could only be tasted through the boundaries of their sensory realm, and what language was able to express.

Seremetakis uses her story of the rodhákino to show how history is embedded in sense memory, and sense memory is embedded in stuff. Every time a thing like the rodhákino is erased from the material horizon of a culture, whole atmospheres, histories, memories, and sensibilities associated with its taste, color, scent, and texture disappear too. I realized this when, after many years of living in the city, I went home and smelled the scent of fresh cut grass. Old feelings, old bodies were revived.

I was born a little over a decade after my family arrived in the United States. I’ve never been to Vietnam, and so Vietnam is an idea that I’ve never directly experienced.

The new peaches, Seremetakis goes on to say, might approximate the rodhákino, but only by displacing one set of sense memories for another, almost without notice. She writes, “Sensory changes occur microscopically through everyday accretion; so, that which shifts the material culture of perception is itself imperceptible and only reappears after the fact in fairy tales, myths, and memories that hover at the margins of speech.” And as perception shifts imperceptibly, memory shifts imperceptibly along with it.

I was born a little over a decade after my family arrived in the United States. I’ve never been to Vietnam, and so Vietnam is an idea that I’ve never directly experienced: “digested through memory and language” is an apt description. I have folded every little diactric into the cultural grammar of what it means to me to be Vietnamese: language, food, manners of dress, ways of doing hair, styles of blinking, sneezing, praying, of expressing the pain of a headache, of organizing a family, smells, fingers and toes and the shape of toenails, laughing, holding a bowl of rice, inhabiting a house, the specific shadows of a basement, of the dusty sunlight streaming in through the back door of the basement laundry room, where, while my grandmother did her laundry, I would stare out the glass, smudging it with my fingertips, memorizing the particular shade of the Pennsylvania green grass. As a result, I speak an oddly accented language, one that has never touched its native soil.

The child in Seremetakis’ story is silent, barely present. In their stead, I want to speak back: this imagined rodhákino was real to me, a “fiction” of witnessing. I understood being Vietnamese through a smudged glass: the rodhákino, the memory of Vietnam, became real through an act of interpretation shaped by the stories of those around me, and an inheritance of sensory artifacts. But since most Vietnamese refugees fled with very few belongings, and of course, because history is often nation-centered, what little history or memory there was formed over a psychic territory mostly defined by loss. What if fictions of witnessing can be a form of record keeping in which the struggles over meaning are played out? What if meaning appears as a kind of poetry, allowing something outside of conventions of realism to exist? What if they carry the unknown and not understood into the future, protecting its unknowability as it protects its ability to exist?

When I first began my MFA in Cross-Genre Writing I was a “fiction writer,” but I was mostly surrounded by “poets.” As a result, in workshops there was a lot of attention paid to the space on the page, how it connected to the reader’s body: how space taught the reader to breathe and find rhythm among words, how the size, shape, and design of the gap produced a type of mental choreography for the reader to make associative leaps in the logic between sections of text. We considered questions such as: Do you include a little gap or a page break? A little insignia, like a stepping stone between sections, or a giant strip of white? The shape of the gaps became very important in our workshops. They suggested a logic between one section and another that came before, or after. A whole piece, including its white space, could be viewed as a score for a neurological dance, for in the act of reading the viewer moves from marks on the page to an entire imagined world. But of course, the movements of the mind, the chambers of imagination these texts opened, were never articulated per se. The logic was never defined; it was maybe never even understood. That’s the reader’s job.

Now I am a PhD student and I study Screen Cultures, where I have been introduced to the power of the cut in the presentation and perception of a film. One way to think of this is that, as the cut divides one consecutive sequence from the next, the viewer stitches these shots together even if they are very far away in space and time (think of when a character gazes outside the frame and the film cuts to a landscape, the place they’re “looking at”). Another way to think of this is that, by identifying with a certain character’s gaze or interiority, the viewer is sutured into worldviews considered objective because they are naturalized through the logic of editing. In other words, we stop seeing the cut.

The cut and the gap require a reader and viewer to produce new meaning. Maybe I have been taught to witness and absorb as if everything were a book or a movie, but I keep thinking about the value of gaps, cuts, and perspectival orientations for the witness, because a reader and a viewer are also a type of witness, an interpreter. I think about the associations I make between sequences, the “reading,” that I do as I cross between one cultural sphere and another. What is a gap in memory? What do I see within it? How do I connect one constellation of meaning to the next?

For the past two years I have been considering the question of how watching television shaped the experience of cultural transition for the Vietnamese in America.

Diasporic Vietnamese history is, in many ways, a history of gaps, a minor history in every society that hosts it. Its presence is always accompanied by its shadow, absence, how much has been lost: the families who came with nothing, the families that were split up, those who were lost and died along the way. The things that were left behind. The scarcity of archives, the way history was written from the artifacts that remained. The analogic rodhákino(s): things and their spheres of sensation and sensibility, memory and history, that have gradually faded. I imagine that when, as a child, I “digested” the story of the Vietnam, I gazed beyond the frame towards the floating peach. Outside the frame and around the peach everything was blank. A blank space that was not blank. A space of:

Silence

Stillness

Absence

Loss

The unsaid

The unseen

The sublimated

The suppressed

The undirected

The invisible

I have been told my family’s story of leaving Vietnam countless times. I have heard about their previous lives, their journey to the US. Still, as I recall them, the facts seem insufficient to my comprehension of what happened. I cannot guiltlessly retell the tale without questioning my own position, my perceptual or narrative framing, my own experience in what I choose to tell or not. My privilege in telling the story. Every act of retelling is a maternal gesture and a violence. How do I relay my own particular position as vicarious witness or child who digested the tale? What did I witness? What is my story to tell? How can I describe the taste of my own particular rodhákino, how can I deny the belief that it’s tasteless? It has a taste.

The final chapter of le thi diem thuy’s book The Gangster We Are All Looking For begins with the narrator’s father at home, channel-surfing and watching the news. He notices a woman standing in a field of grass, pointing to the ground and shaking her head. Like channels changing, the chapter begins to cut back and forth between scenes of the narrator’s drowned brother being pulled from the South China Sea and scenes of the narrator’s father drifting from room to room, sometimes watching television or thinking about what he’d watched on television. The scenes mimic the abrupt and nonlinear cuts between one channel and another, as if the action of changing channels conveys the experience of suturing the memory of Vietnam with life in America. Later the father realizes the woman in the field of grass had been crying. Le writes:

Every time the camera came back to her, she shook her head and pointed to the ground. When the camera shot the ground, all he had seen was a lush field. As lush as a rice paddy, he remembered thinking. Now he had a feeling that the woman was pointing to bodies, unseen bodies, under the grass. As she directed the eye of the camera back to the grass, she kept crying because of what it could not see and what she could not stop seeing.

For the past two years I have been considering the question of how watching television shaped the experience of cultural transition for the Vietnamese in America. How to do this? To my knowledge there have been no television shows about Vietnamese-American families, or made for Vietnamese-American audiences. Portrayals of Vietnamese-Americans in popular media are largely restricted to portrayals of the Vietnamese during the Vietnam War, often through an American gaze, and Vietnamese-Americans as an audience demographic are often lumped into the imagined panethnic category of “Asian-American.” I know this question is answerless. It relies on the unseen, immaterial, and ephemeral in an archive that has not yet been excavated, if it exists at all.

When I read this passage, I latched on to the image of the series of witnesses: camera, father, daughter, reader. How each act of witnessing morphed and mutated the image of the green grass according to the position of the witness as they encountered the cut. I’m asking these questions because I think that freeze-framing the imagined images might reveal a way in which inchoate experiences refract across gaps of silence, like tuning into a frequency where past and present find their shared signal and give way to a new thought. A cross-cultural suture.

I am listening to these signals, compiling these frequencies wherever I find them in hopes of making ephemeral artifacts visible. I know that so much has been lost. The textures and accents have changed. But so much remains, so much new information is being added if only we can decipher the code.

_______________________________

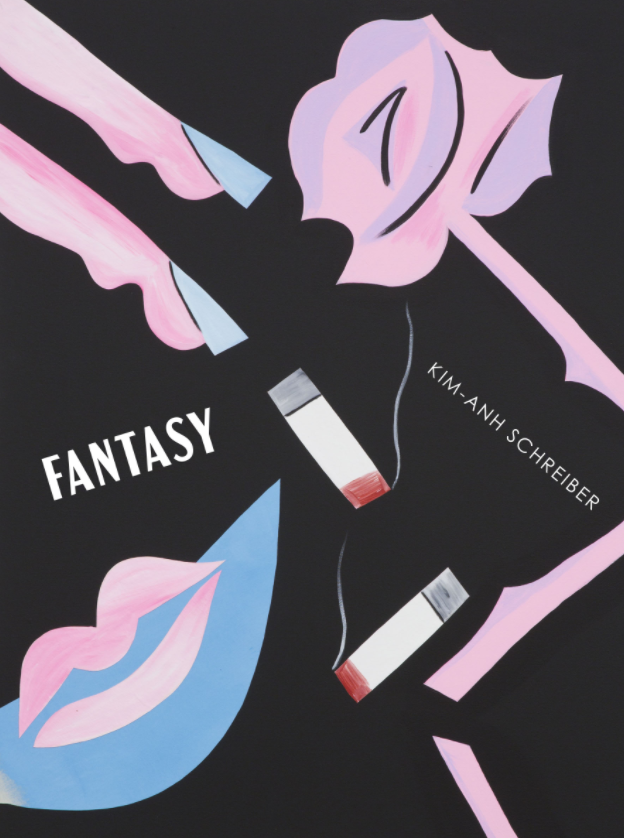

Kim-Anh Schreiber’s Fantasy is available now from Sidebrow Books.

Kim-Anh Schreiber

Kim-Anh Schreiber’s cross-genre novel Fantasy was published by Sidebrow in March 2020. Her multidisciplinary work has appeared in outlets such as Bitch, The Brooklyn Rail, littletell, Emergency Index, BWSMX, the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, and elsewhere, and has been supported by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the New York Center for Book Arts, and UC San Diego, where she received her MFA in Writing. She lives in Chicago, where she is a PhD student in the Screen Cultures program at Northwestern University.