“A Ghost Is a Memory.” On Bodies, Belief, and the Places Ghost Stories Live

GennaRose Nethercott Tells the Story of a Long Night in an Old House

The proprietor’s name is Amy (except that, of course, it isn’t). She’s a kind, petite woman in her forties, the owner of a ghost-themed bookstore in a small southern city. I won’t tell you which city. It’s for your own safety. This is, after all, a ghost story. And most importantly: it’s true.

The bookshop leans not toward horror, it turns out, but romance. Amy herself is a romance author—penning time travel bodice rippers in her evenings away from the bookshop counter.

“Customers sometimes complain that the shop isn’t spooky enough,” she says when I ask about the store’s branding. “But I just tell them it’s haunted by the ghosts of great literature.” She wiggles her fingers.

A bit of a cop-out—but sure. Whatever.

I’m a few months into a tour with my first book, The Lumberjack’s Dove—a long narrative poem inspired by folklore. The publication was my big break, so I wanted to do it up right. For me, “do it up right” meant spending eight solid months on the road, in a new city every few days, as I performed a hundred live readings. Oh also, these readings involved puppets—but that’s a story for another time. This story will be cursed enough without throwing puppets into the mix.

Tonight, my reading goes well. The crowd is small but sweet, and I sell a couple copies of Lumberjack. As I pack up, Amy asks where I’m sleeping that night, and I tell her the truth: that like so many other nights on this signing tour, I’m planning to drive around until I find a quiet, residential street, park, and curl up in the backseat.

“Oh!” she peeps. “Come stay with me, I have extra space.”

Outside, the dusk tosses with wind and a steady, thudding rain. I have a good sleeping bag… but a real bed would be a luxury. I thank her, and accept the offer.

As we leave, Amy stalls in the doorway. “I should warn you,” she says. “The house, I think of it as… well… an experiment in Southern decay. You’ll see what I mean.”

*

A few days prior, at a Q&A after one of my readings, a young man in the audience raised his hand:

Do you believe in ghosts?

“Well, that depends.” I told him. “What is a ghost?”

What I love most about ghost stories is their malleability. A ghost can be a heart beating beneath a floorboard. A father, appearing to his son to beg for vengeance. A party dress worn by your husband’s first wife, which you, the new wife, now don. A ghost can be a house, or a mirror, or a shadow. It would be reductive to define ghost-hood as simply a deceased person’s spirit appearing in the mortal realm. So then, how do we define a ghost?

I personally have one, simple definition: a ghost is a manifestation of longing.

In “The Telltale Heart,” the protagonist’s longing comes from regret, from guilt. A longing to undo a terrible act of violence—which manifests as a heartbeat thudding in the floor. In Hamlet, the late King appears to his grieving son: a boy longing for his deceased father. In Rebecca, an insecure young bride longs to be loved as strongly as she’s convinced her predecessor was—to the point of manifesting the woman all around her. The list goes on. At the root of every ghost, a yearning. A tug, in which a living person reaches so fervently toward something absent, that the absence becomes bodied.

I personally have one, simple definition: a ghost is a manifestation of longing.

As anyone who has known loss understands full well, lack is not in fact, an absence at all. It is a presence. A person we love dies, or leaves, or changes, and a gap forms. It takes on their shape. Mimics their movement. Echoes their voice like a mockingbird. We feel this gap take up space, filling every place our lost one once was, and now isn’t. It reflects in mirrors. Flickers in candle flames. A phantom.

Do you believe in ghosts?

Of course. I have seen longing grow legs and follow me.

*

I drive behind Amy’s orange Honda, following her taillights, which glow like twin lantern bearers cutting through the rain. Turning right onto a muddied, pothole-filled drive, we wend through a tunnel of oaks, dripping with Spanish moss. Eventually, we reach the end of the drive. The darkness parts. And there, illuminated in car headlights and draped in darkness, squats the house.

It’s a towering white mansion with looming archways, floors stacked one atop another like a sinking layer cake. Eleven white pillars on each story hoist up sagging balconies. Pale balustrades stripe the façade like rows of boney ribs, and the paint is peeling off in ringlets.

We both get out of our cars and Amy appears beside me. “This is The Hall. It’s been in my family for ninety-nine years,” she says. “It belonged to my great aunt. Then another great aunt. Then my aunt, and now me. I like to think of it as my own Grey Gardens.”

“How many people live here?” I ask, gawking.

“Just me!”

Ohhhhh. I get it now. I’m that character in every monster movie who gets caught in a rainstorm, and only needs to use the phone, or borrow some gas, or dry off—and ends up as a snack for vampires. Cool. Coolcoolcool.

Amy leads me up to the looming double doors and slides a key into the lock. It clicks open and the doors swing wide. Inside, the lavish interior looks as if it hasn’t been altered in a century. Burgundy medallion carpets pool across the floor. In the adjacent dining room, multi-armed candelabras teeter on a long banquet table. In the 1920s, I’m told, this table had hosted literary elites for midnight salons. Now, the chairs are lone and empty. White sheets drape over antique settees, and dust wafts up from our footsteps in grey clouds.

There are two specific décor choices in The Hall particularly worth dwelling on:

1. Hanging all throughout the house are large, formal paintings of little Victorian girls in prim silk dresses. The paintings have not been well maintained—and the girls’ faces have begun to rot. (“Oh, those are my aunts,” Amy clarifies, clarifying nothing).

2. Every single free surface is covered in hundreds (yes, hundreds) of wooden Christmas nutcrackers. (“My aunt…” Amy says. “It was just one of her…things.”)

My host leads me up three flights of stairs to my room. It’s part of a larger suite, one of seven that comprise the mansion.

“That’s funny,” Amy says into the gaping entryway when we arrive. “I don’t remember leaving that door open… And no one has stayed in this room in years…”

*

At a certain point, it doesn’t matter whether literal ghosts (ghosts of the dead) are real or not. What matters is that people believe they are.

The “tulpa” (born from a blend of Theosophical philosophy and Tibetan Buddhism) is a creature made from thought. The idea behind tulpamancy, or the making of tulpas, is that if enough people conceptualize the same imagined being and focus their attention on it, that attention will eventually make the figure real. In other words: if enough people believe in something, that thing can manifest.

I have never believed in a literal, sentient God. And yet, wars have been fought in God’s name. Empires have risen and fallen to one god, to many gods. And at that point, the “realness” of a deity no longer matters. What matters is the impact. What matters is a battlefield soaked in blood. That blood is just as red whether or not the god for whom it was shed exists. And at that point, the god may as well be real, for it’s altering human action—and human action alters the world.

Have you ever sprinted up the basement stairs, two at a time, imagining a spectral pursuer at your back? Have you taken the long way home at night to avoid passing through the cemetery under a veil of moonlight? Are ghosts real? Now that you have accommodated them—they are. Born of belief. Born of fear. Born of a longing that maybe, just maybe, this world is more than meets the eye.

*

I help Amy make the bed, which boasts a massive headboard carved with tendrilling flora, taller than myself even when I stand on the mattress. I try not to pay much attention to the tiny, identical, Victorian child’s bed—a crib, really—directly beside my own.

“There’s a guest book around here somewhere,” Amy says. She rifles through drawers. One is filled entirely with JFK memorabilia. “Aha!” She tosses me a little green notebook. “You should sign it.”

Before she leaves, she turns to me again. “Listen, when you wake up in the morning… don’t… well, don’t explore the rest of the house.”

You got it, Bluebeard.

She leaves, and I’m alone. I stare at myself in the mirrored armoire across from the bed. My reflection wavers in the warped glass, making me look a little like the disintegrating aunts in their girlhood oil portraits. Then, I remember the guest book.

August 2014

There is something magical about this place—but also scary.

September 2011

One night we took a digital camera out back and took pictures in the dark. Turned black in all directions except over exposed when pointed toward [road name]. Again and again, same results. Black, and then white light where there was nothing ??????? No explanation.

June, 2008

There were lots of laughs about the idea of seeing a ghost in the night…until I saw the outline of a baby’s face in the crib next to the bed.

*

In Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay “The Uncanny,” the psychologist posits that the difference between fantasy and horror boils down to this: fantasy is a fantastical thing happening in a fantastical world. Horror is a fantastical thing happening in our world. So dragons, for example, don’t scare us because they sit in their rightful context. They aren’t considered “monsters.” But Godzilla, that’s a monster—not because it’s vastly different from a dragon, but because it is here rather than there. It’s not the thing itself that frightens us, Freud claims, but the chafing sensation of something leaking into a place where it doesn’t belong. A violation.

At a certain point, it doesn’t matter whether literal ghosts (ghosts of the dead) are real or not. What matters is that people believe they are.

Taking Freud’s concept a step further, Theodora Goss writes, “Categorical boundary crossing, or hybridity, has marked monsters from the beginning.” Her essay, “Listening to Krao: What the Freak and Monster Tell Us,” suggests that it’s not only a figure creeping into our world, but also a violation contained within a horror figure’s body that frightens us. Werewolves are human yet animal. Vampires are living yet dead. Hags are feminine yet dangerous. All elements that our understanding of the world has deemed contradictory—now shoved together in one form. Again, a chafing.

And ghosts? Not only do they breach the literal boundary between our world and the Otherworld, but they cross the boundary of time, too. They are, in their very bodies (or lack thereof) inhabiting the present and the past, at once.

A ghost is a memory.

*

Now, I may not believe in literal ghosts of the dead. But if they do exist, The Hall is surely where they’ll get me.

Frantically, I take photos of everything around me—journal entries included—and text them to my friend Cassandra. It’s good to have a record when someone vanishes without a trace, right? Next, I Google “protective sigils” and scrawl a tiny pitchfork rune on my wrist in ballpoint pen. And still—I try to keep my eye off the cradle, mere feet from my bed. My blankets are mercifully heavy, and eventually, there in the darkness as the rain continues to fall, I sleep.

I wake in the night to the sound of scratching.

Scriiiiiitch. Scriiiiiiitch. Scriiiiiiitch.

In my half-unconscious state, I consider the sound. A dead baby wouldn’t have nails long enough to make a sound like that. Probably a raccoon.

Scriiiiiiitch. Scriiiiiiitch.

The cradle is a black stain in my periphery.

Scriiiiiiitch. Scriiiiiiitch. Scriiiiiiitch.

The dragging is heavy. It is coming from under the bed.

I close my eyes tight. Slip my head beneath the covers. Wait, and wait, and wait, and eventually, I must fall asleep—because that’s when the dreams find me.

All night, I dream of women in Victorian gowns trailing through the corridors of The Hall. One pauses at the top of the stairs. She looks right through me.

*

No ghost story only contains ghosts. It must, too, contain the living.

A breathing, bodied counterpoint to chafe against. A comparison.

A scritch, scritch, scritch, between life and death.

This one, of course, is no different. That’s why I’m here.

*

By morning, sunlight streams through the window. The rain is ended. I’m alive. I grab my things, tug on my shoes, and run. Out of the bedroom. Down the three twisting flights of stairs. Through the labyrinthine parlors. As I sprint, I snap photos of everything I pass: The nutcrackers. The girls, staring from the walls. The chandeliers dripping with crystal. But one thing I don’t do is slow down.

*

What was I longing for when I first stumbled into The Hall?

A night off the road? A washroom with running water? A warm bed?

A story?

A ghost?

What absence had manifested for me that night in November, after months of travel with nothing but a lowering gas gage and a stack of books in tow? What gaps had bloomed, far from home? So many cities lay behind me, which I’d passed through traceless, as if passing through walls.

*

Bursting into the day, my car waits for me ahead. I leap in, start the engine. As I bullet down the drive, I can feel The Hall behind me, a planet with a gravity all its own. It tugs, begging me to turn around. To toss a glance over my shoulder. To flick my eyes up to my rearview mirror. But I don’t look back.

After all, everyone knows—that’s how a sequel starts.

________________________________

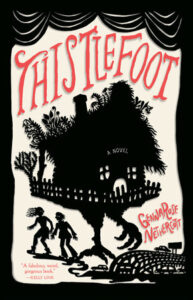

Thistlefoot by GennaRose Nethercott is available now via Anchor.

GennaRose Nethercott

GennaRose Nethercott’s book The Lumberjack’s Dove was selected by Louise Glück as a winner of the National Poetry Series for 2017. A born Vermonter, she tours nationally and internationally performing from her works and composing poems-to-order for strangers on an antique typewriter with her team The Traveling Poetry Emporium. Thistlefoot is her first novel.