1. a female text

thug mo shúil aire duit,

thug mo chroí taitneamh duit,

how my eye took a shine to you,

how my heart took delight in you,

—Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill

this is a female text.

This is a female text, composed while folding someone else’s clothes. My mind holds it close, and it grows, tender and slow, while my hands perform innumerable chores.

This is a female text borne of guilt and desire, stitched to a soundtrack of cartoon nursery rhymes.

This is a female text and it is a tiny miracle that it even exists, as it does in this moment, lifted to another consciousness by the ordinary wonder of type. Ordinary, too, the ricochet of thought that swoops, now, from my body to yours.

This is a female text, written in the twenty-first century. How late it is. How much has changed. How little.

This is a female text, which is also a caoineadh: a dirge and a drudge-song, an anthem of praise, a chant and a keen, a lament and an echo, a chorus and a hymn. Join in.

***

2012

Every morning of mine is much the same. I kiss my husband, feeling a pang as I do so – no matter how often our morning goodbye is repeated, I always miss him when he leaves. Even as his motorbike roars into the distance, I am already hurrying into my own day. First, I feed our sons, then fill the dishwasher, pick up toys, clean spills, glance at the clock, bring our eldest to school, return home with the toddler and the baby, sigh and snap, laugh and kiss, slump on the sofa to breastfeed the youngest, glance at the clock again, read The Very Hungry Caterpillar several times, try to rinse baby-spew from my ponytail into the bathroom sink, fail, make a tower of blocks to be knocked, attempt to mop, give up when the baby cries, kiss the knees of the toddler who slips on the half-washed floor, glance at the clock yet again, wipe more spilled juice, set the toddler at the table with a jigsaw puzzle, and carry the youngest upstairs for his nap.

The baby sleeps in a third-hand cot held together with black gaff tape, and the walls of our rented bedroom are decorated not with pastel murals, but with a constellation of black mould. I can never think of a lullaby, so I resort to tunes from teenage mixtapes instead. I used to rewind ‘Karma Police’ so obsessively that I wondered whether the brown spool might snap, but every time I pressed play the machine gave me the song again. Now, in my exhaustion, I return to that melody, humming it gently as the baby glugs from my breast. Once his jaw relaxes and his eyes roll back, I creep away, struck again by how often moments of my day are lived by countless other women in countless other rooms, through the shared text of our days. I wonder whether they love their drudge-work as I do, whether they take the same joy in slowly erasing a list like mine, filled with such simplicities as:

School-run

Mop

Hoover Upstairs

Pump

Bins

Dishwasher

Laundry

Clean Toilets

Milk/Spinach/Chicken/Porridge

School-run

Bank + Playground

Dinner

Baths

Bedtime

I keep my list as close as my phone, and draw a deep sense of satisfaction each time I strike a task from it. In such erasure lies joy. No matter how much I give of myself to household chores, each of the rooms under my control swiftly unravels itself again in my aftermath, as though a shadow hand were already beginning the unwritten lists of my tomorrows: more tidying, more hoovering, more dusting, more wiping and mopping and polishing. When my husband is home, we divide the chores, but when I’m alone, I work alone. I don’t tell him, but I prefer it that way. I like to be in control. Despite all the chores on my list, and despite my devotion to their completion, the house looks as cheerily dishevelled as any other home of young children, no cleaner, no dirtier.

So far this morning, I have only crossed off school-run, a task that encompassed waking the children, dressing, washing, and feeding them, clearing the breakfast table, finding coats and hats and shoes, brushing teeth, shouting the word ‘shoes’ several times, filling a lunchbox, checking a schoolbag, shouting for shoes again, and then, finally, walking to the school and back. Since returning home, I have still only half-filled the dishwasher, half-helped my son with his jigsaw, and half-mopped the floor – nothing worthy of deletion from my list. I cling to my list because it is this list that holds my hand through my days, breaking the hours into a series of small, achievable tasks. By the end of a good list, when I am held again in my sleeping husband’s arms, this text has become a sequence of scribbles, an obliteration I observe in joy and satisfaction, because the gradual erasure of this handwritten document makes me feel as though I have achieved something of worth in my hours. The list is both my map and my compass.

Now I can feel myself starting to fall behind, so I skim the text of today’s tasks to find my bearings, then set the dishwasher humming and draw a line through that word. I smile as I help the toddler find his missing jigsaw piece, clap when he completes it, and finally resort to the remote control. I don’t cuddle him close as he watches The Octonauts. I don’t sit on the sofa with him and close my weary eyes for ten minutes. Instead, I hurry to the kitchen, finish mopping, empty the bins, and then check those tasks off my list with a flourish.

At the sink I scrub my hands, nails, and wrists, then scrub them again. I lift sections of funnels and filters from the steam steriliser to assemble my breast-pump. These machines are not cheap and I no longer have a paying job, so I bought mine second-hand. On my screen, the ad seemed almost as poignant as the baby shoes story usually attributed to Ernest Hemingway –

Bought for €209, will sell for €45 ONO.

Used once.

Every morning for months this machine and I have followed the same small ritual in order to gather milk for the babies of strangers. I unclip my bra and scoop my breast into the funnel. It’s always the right breast, because my left breast is a lazy bastard: by a month post-partum it has all but given up, so both baby and machine must be fully served by the right. I press the switch, wince as it jerks my nipple awkwardly, adjust myself, and then twist the dial that controls the intensity with which the machine pulls the flesh. At first, the mechanism draws fast and firm, mimicking the baby’s pattern of quick suck, until it believes that the milk must have begun to emerge. After a moment or two the pump settles into a steady cadence: long tug, release, repeat. The sensation at nipple level is like a series of small shocks of static electricity, or some strange complication of pins and needles. Unlike feeding the baby, this process always stings, it is never pleasant, and yet the discomfort is endurable. Eventually, the milk stirs to the machine’s demands, un-gripping itself somewhere under my armpit. A drop falls from the nipple to be quickly sucked into the machine, then another, and another, until a little meniscus collects in the base of the bottle. I turn my gaze away. There are mornings, on finding myself particularly tired, that I might daydream a while, or make a ten-minute dent in a library book, but today, as on so many other days, I pick up my scruffy photocopy of Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire, inviting the voice of another woman to haunt my throat a while. This is how I fill the only small silence in my day, by turning up the volume of her voice and combining it with the wheeze-whirr of my pump, until I hear nothing beyond it. In the margin, my pencil enters a dialogue with many previous versions of myself, a changeable record of thought in which each question mark asks about the life of the poet who composed the Caoineadh, but never questions my own. Minutes later, I startle back to find the pump brimming with pale, warm liquid.

__________________________________

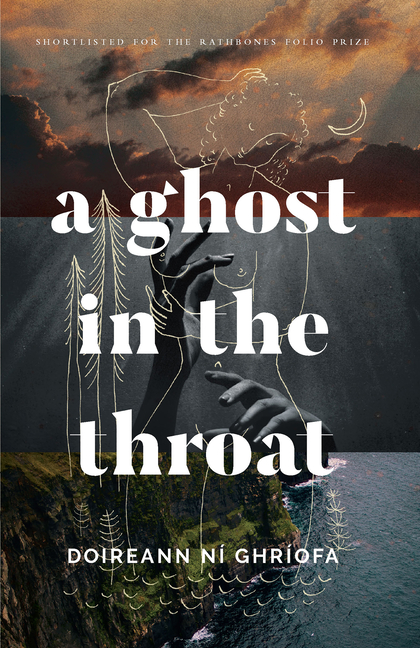

Excerpted from A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa, with the permission of Biblioasis. Copyright © 2021 by Doireann Ní Ghríofa.