A Different Side of the Self: On Finding Freedom By Telling My Story in English

Atash Yaghmaian: “In English, I’m just someone—free, unclaimed, and therefore, for the first time, self-defined.”

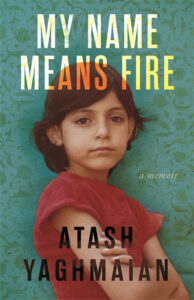

When it came time to write my memoir, My Name Means Fire, I chose to write it in English.

There’s irony in that, of course. I wrote in English, but my name, “Atash”—which means “fire” in Persian—is where my struggles started. After my father left my mother, shortly after my birth, my mother saw my name as a curse that “burned” her marriage. I became, in her eyes, a destructive flame.

My earliest memories were forged in Persian: the smell of jasmine on the Tehran wind, the shouted prayers from rooftops, the careful hush that fell over my house in the presence of men. My first silences were in Persian. My first shame, too. And that is why my first true voice—the one that could hold complexity, contradiction, grief, even anger—came in English.

Had I written about my life in Persian, I would have softened the edges. I might have told the story of a girl who left Iran, but I would never have talked about my Dissociative Identity Disorder, my multiplicity. The word for multiple personalities in Persian (chand shaksiyati) is a slur for someone who can’t be trusted. I would have worried too much—about what my mother would think, about how my community would respond, about whether the shame would double back and swallow me. I would have written in code. Or worse, I might not have written at all.

Persian is my first language—the one I dream in, the one I was born into. It is the language of lullabies and ghosts. It was in Persian that I first learned how to lie, how to flatter, how to stay silent when I was hurting. It was in Persian that I learned how to be a dokhtar-e khoob—not just “good girl” in English, but a girl who knows how to shrink and, when needed, vanish.

At first, I didn’t actually know why I chose to write in English. I told myself that English was just more practical, that it gave me a wider readership, a larger stage. But over time, I began to understand a deeper truth: writing in English gave me just enough distance to survive the telling. English offered a subtle dissociation, not unlike the psychological kind that saved me when I was a child. English became a buffer, a soft curtain between myself and the memories that threatened to undo me.

In Persian, I regress. I slip into the daughter-role: obedient, deferential, hoshyar—alert to danger, to other people’s mood shifts, trained in the art of emotional triage. In English, I have a shape. I have edges. I can say no without apologizing. I can say I’m not ready and mean it. I can say leave me alone—words I didn’t even know I was allowed to utter.

English became a buffer, a soft curtain between myself and the memories that threatened to undo me.

English gave me a vocabulary for boundaries. It let me name things plainly, even when those things were brutal. English let me see myself not only as the subject of the story, but as its author. And for a girl who once believed she had no control over her own narrative, that is no small thing.

There is a particular type of emotional safety that writing in a second language can afford. English wasn’t tied to the same expectations of obedience, modesty, or loyalty. In Persian, I am someone’s daughter, someone’s sister, someone’s burden. In English, I’m just someone—free, unclaimed, and therefore, for the first time, self-defined.

I don’t know how to explain this to people who haven’t lived between languages. But those who have usually nod when I tell them this. They understand how, strangely, a second language can become a second home—not because it is more “authentic,” but because it allows you to change.

When I was a child, my second home was the House of Stone, a magical place I dissociated to when my reality became unbearable. Not surprisingly, it was in English that I first was able to explain my inner world to others. Their validation, too, came in English.

My Name Means Fire, my memoir, is not just a story about multiplicity or survival—it is about truth-telling. It is about the act of translating the unspeakable into something legible. It is about naming what was once hidden and holding it up to the light. It’s about what happens when a woman steps out of silence—not just across cultures or political regimes, but across languages, families, and selves.

I don’t know if the book will ever be translated into Persian. Maybe it will. And maybe I’ll be ready for that. But for now, it lives in English. The language that allowed me to thrive. The language of my womanhood. The language in which I stopped hiding.

I wrote this book for the ones who had to change something about themselves in order to stay whole. The ones who needed to leave their mother tongue in order to find their true voice. And I wrote it for the parts of me that once trembled too hard to speak, but now have become fountains of story.

__________________________________

My Name Means Fire: A Memoir by Atash Yaghmaian is available from Beacon Press.

Atash Yaghmaian

Atash Yaghmaian is a writer and a psychotherapist whose stories and articles about mental health and Iran have appeared in Ms. magazine, the New York Daily News, The Mighty, and Thrive Global, among others. Born in Tehran, Atash migrated to the United States alone at the age of 19, fleeing war, trauma, and abuse. She blogs at atashyaghmaian.com.